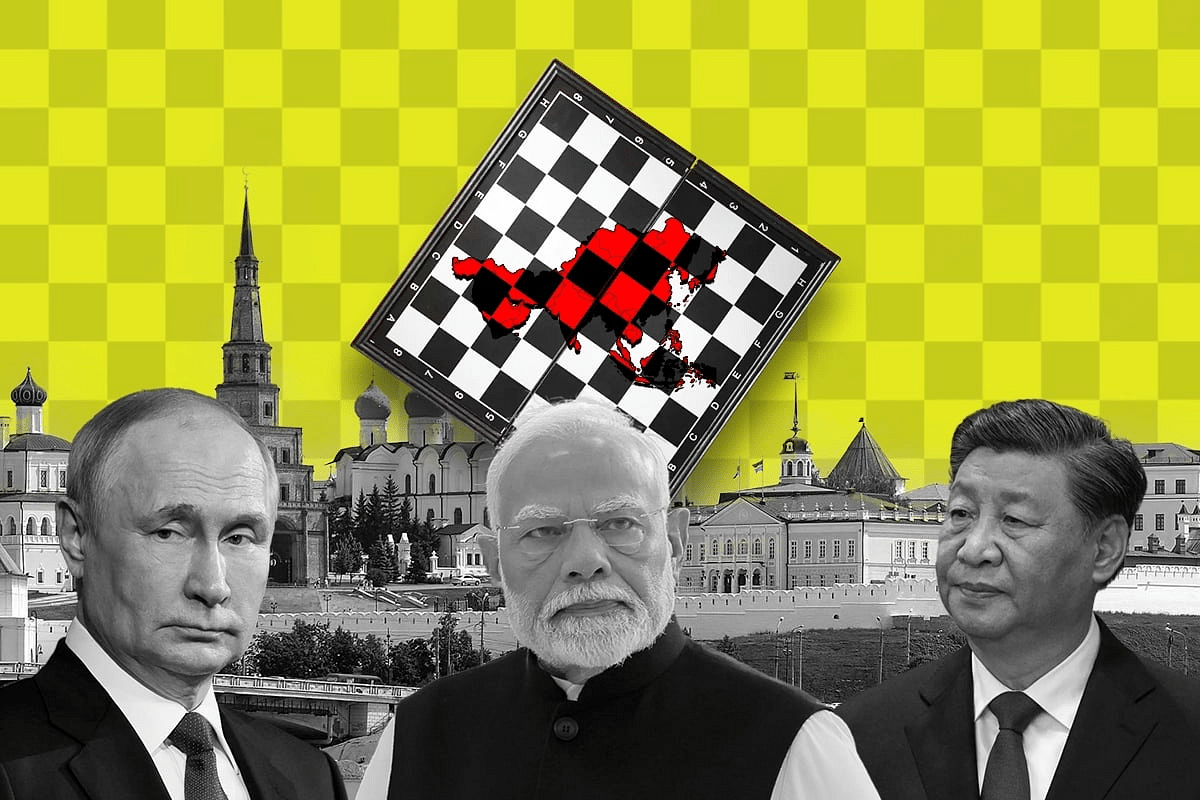

The recent meeting between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Chinese counterpart, President Xi Jinping, at Kazan in Russia marked the end of a fairly hectic week in Indian geopolitics.

It began with Indian Foreign Minister Dr S Jaishankar’s visit to Islamabad – the first by an Indian official of such seniority in a decade – for a multilateral conference.

This was followed by news that the Indians and Chinese had worked out a disengagement pact in Ladakh. Finally, after almost five years of the worst military standoff in modern history between the two largest nations on the planet, there was some hope that a modicum of normalcy might return to the bleak, desolate Aksai Chin region.

And this pact was formalised when the leaders of the two nations met in Kazan. Two giants with conflicting national interests, who did not get along, had grudgingly agreed to try to work together on the soil of a third nation.

The importance of this bilateral meeting cannot be underscored enough. It also meant many things to many people at multiple levels.

To a legion of Indian sceptics in the strategic sphere, this disengagement pact, while no doubt welcome, did not mean that our troops could now be redeployed to the plains because the Chinese still retain the ability to deploy faster than us in some areas of the Aksai Chin region.

But to the realists, the past week meant that the Chinese had blinked because the bottom line is that India adamantly demanded a return to the pre-Galwan-clash status quo ante bellum (the state existing before the war), and that is what we got with the disengagement pact – at least on paper.

For the strategists in Rawalpindi, it meant more sleepless nights, more hand wringing, and heightened fears that it could be a red-hot winter in the Neelum Valley sooner than they think. If a friendly Dr Jaishankar is the scariest sight in the world today (he smiled when he visited Islamabad last week), the only thing worse for a Pakistani general is footage of Modi and Xi shaking hands.

The reasons for such woes are grave because the principal implication of the meeting at Kazan is that, if the Chinese have indeed now deigned to climb down a few rungs of the escalation ladder vis-à-vis India, it is only because they have chosen – perhaps temporarily – to compromise on some of their strategic interests in Pakistan.

That old iron-brother concept has gotten a bit rusty. As a result, because China sees value in engaging positively with India for its own benefit, Pakistan cannot bank on unflinching Chinese support to the extent that it used to.

Instead, and spare a thought for the handwringers of Rawalpindi here, Pakistan has been shown up for what it actually is to the Chinese – an expensive liability that may be approaching its shelf life.

But the implications don’t stop there.

Many Western nations will be watching this week with a wariness which rivals that of Indian sceptics because the last thing they need is India and China getting friendly by even a smidgen.

For them, life is beautiful only as long as Asia is in flames because the day India and China choose to smoke the peace pipe, the Occident’s ability to direct the course of global affairs will come to a juddering halt.

That alarmism has already manifested in their atrocious intellectual commentary, with a few writers employing Sith-level absolutism to wonder if India and China making up would be a challenge to America, or, even more hilariously, on whether India would now join China’s anti-Western alliance.

What’s worse is that the West has no clarity on its collective interests. As a result, all they have is blinkered Pavlovian hankering for the way their world once used to be. But really, that is their problem because, as the bilateral at Kazan showed, there is nothing they can do to prevent huge economies like India and China from pursuing independent paths in their national interests.

To that limited end, Kazan is a representative metaphor for something broader since, agree or not, and taking into account the growing multilateralism of the past quarter century, it must be admitted that we are witnessing the beginning of the deconstruction of the colonial era when large countries like China, India, and Russia will do what they think is in their best national interests irrespective of the opinion or reactions of the powers that have been.

Look at Russia, for example, mired as it has been in a proxy conflict with the West for well over two years now: President Vladimir Putin knows that he cannot get his way with the West in a manner desired unless India and China accommodate each other’s aims to at least a minimal extent (and to put things in perspective, the bilateral at Kazan and the disengagement pact are only that and no more).

Therefore, it is very much in Russia’s self-interest to try and see if it can make India and China work together.

Similarly, the Chinese know that they will be progressively cut out of the Indian market – peripherally at first, like with the banning of TikTok, and then more comprehensively and viscerally – if they do not compromise, at least to a limited extent, with India’s aims and needs.

Thus, it is in the Chinese national interest to have President Xi shake hands with Prime Minister Modi.

This is how fundamentally the world is changing, something best encapsulated in closing by a dash of irony: did anyone notice that even as China sought to broker a peace between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as India seeks to broker a peace between Ukraine and Russia, as hot and cold wars rage across the borders of these countries and their neighbours, Russia managed to quietly broker a temporary peace between China and India?