Timing, as Danish Pandor would tell you, has a strange sense of humour. Just days after his birthday, the actor found himself fielding a flood of messages, calls, and reactions that felt almost unreal.

Dhurandhar had not only opened strong at the box office but had also begun to settle into public consciousness in a way few films manage. Viewers were arguing, dissecting, rewatching, and theorising. At the centre of this storm stood Pandor’s Uzair Baloch, a character who refuses to be easily decoded and leaves behind a lingering discomfort long after the screen fades to black.

Directed by Aditya Dhar, Dhurandhar arrives at a moment when Hindi cinema is wrestling with scale, realism, and responsibility. The film does not chase spectacle for reassurance. Instead, it commits to detail, research, and moral ambiguity, inviting its audience to confront violence, power, and loyalty without offering simple emotional exits. Within this sharply constructed world, Danish Pandor delivers a performance that has quickly become one of the film’s most debated elements. Uzair Baloch is not framed to be admired or dismissed. He is observed, interrogated, and allowed to exist in all his contradictions.

When News18 Showsha spoke to Pandor a couple of days after his birthday, the actor was still absorbing the magnitude of what had unfolded. The response to Dhurandhar had grown steadily through word of mouth, transforming curiosity into conversation and conversation into near-obsession. For Pandor, the moment carried a rare mix of validation and vulnerability. Years of waiting for the right opportunity had culminated in a role that demanded emotional discipline, ethical awareness, and complete surrender to process.

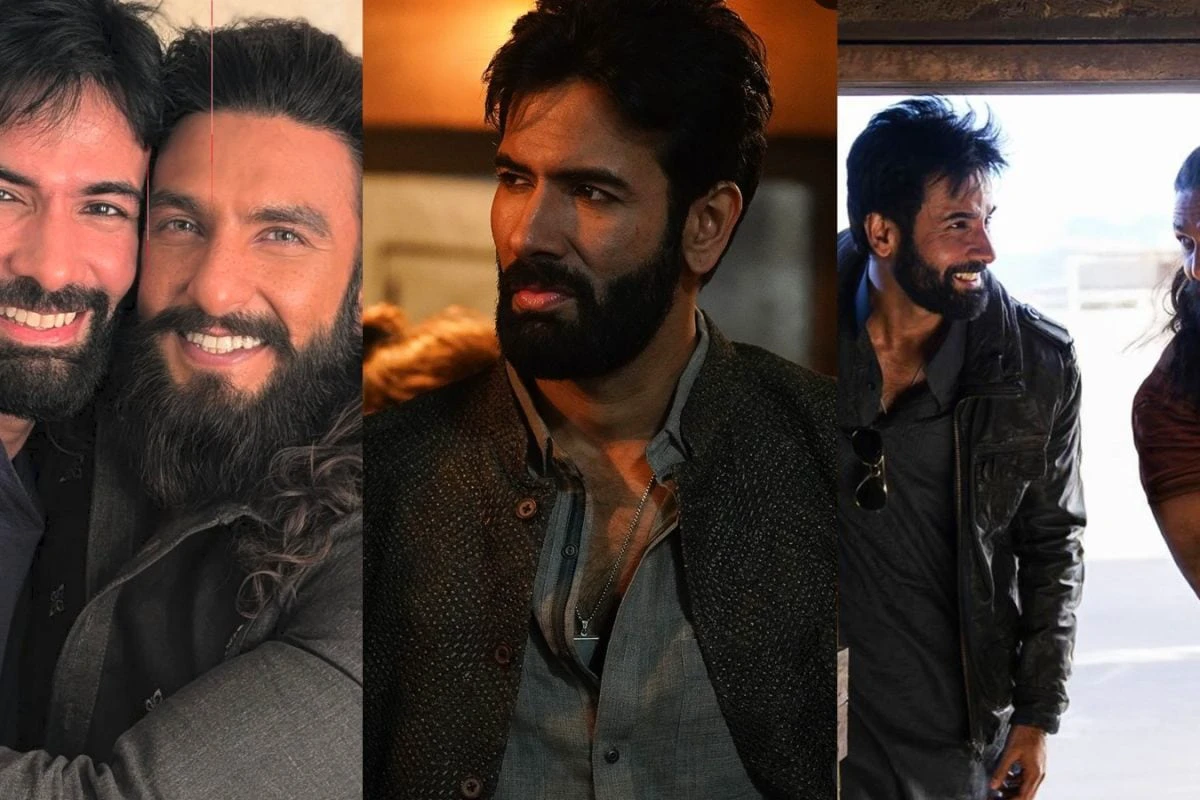

In this exclusive conversation, Pandor retraces the unlikely chain of events that led him to Uzair, from a blind audition to earning the trust of Aditya Dhar. He reflects on the responsibility of portraying a character inspired by a real and controversial figure, the emotional toll of filming the 26/11 sequence, and the quiet camaraderie he developed with Ranveer Singh on set. He also addresses the polarised reactions the film has triggered, the debates around realism versus spectacle, and the growing anticipation for Dhurandhar 2, which promises an even darker turn for Uzair.

What emerges is not a star basking in success, but an actor deeply conscious of the moment he is inhabiting. Grounded, reflective, and acutely aware of the fragility of momentum, Danish Pandor stands at a defining point in his career, one shaped less by noise and more by intent.

Here are the excerpts:

First of all, a very happy belated birthday. The last couple of weeks seem to have been nothing short of extraordinary for you-box office records, critical acclaim, and an overwhelming wave of audience love. How are you processing all of this? Has the scale of Dhurandhar and the response to Uzair Baloch truly sunk in yet?

It honestly has been phenomenal for me. At times, it still feels surreal. I’m extremely grateful for all the love and affection I’ve been receiving. Everywhere I go, there are calls, messages, Instagram DMs-people showering so much warmth and appreciation. It feels really, really good. I guess these are the fruits of hard work finally finding their moment.

Take us back to the very beginning. How did Dhurandhar come your way, and how did Aditya Dhar see Uzair Baloch in you? Also, once you officially came on board, was there a moment during the shoot when you sensed that this film was going to create history?

The credit for Uzair truly goes to Mukesh Chhabra. Mukesh bhai forwarded my audition tape to Aditya sir and played a huge role in getting me on board this project.

This was sometime in 2024 when I received a call from a casting associate at Mukesh Chhabra’s office. They told me I was being auditioned for one of the pivotal roles, but nothing else was disclosed-not the film, not the director, not the cast. Everything was kept under wraps.

The next day, I received the sides, went in, and gave the audition with complete honesty, the way any actor would. After that, there was complete silence for almost a month. Naturally, you assume that maybe it didn’t work out.

Then one fine morning, I got a call from Mukesh bhai himself asking me to send my pictures immediately. I realised he was probably sitting with Aditya sir and showing him my audition, and they wanted to see my look in a particular way. I sent the pictures right away, and that very night, I received a call saying I was creatively locked for the project.

What’s funny is-even at that point-I still had no idea what the project actually was or who was directing it. The next morning, curiosity got the better of me, so I called them back. That’s when I found out Aditya Dhar was directing it. I was honestly stunned.

After Uri, working with Aditya sir had been a dream. Every actor has a bucket list of directors they aspire to collaborate with, and he was right up there for me. He’s not just a phenomenal filmmaker but also an incredible human being to work with.

Slowly, they revealed the rest of the cast-Ranveer bhai, Akshaye sir, Madhavan sir, Sanjay sir-and I remember thinking, My goodness. Sharing screen space with such accomplished actors felt surreal in itself. That’s when it truly hit me that this wasn’t just another film-it was something special.

You’ve previously described Dhurandhar as a make-or-break film for you. In hindsight, who was the Danish Pandor who walked onto the set on Day One-and who was the man who walked off it when the shoot finally wrapped?

I walked in as a human being, and I walked out as one too. That hasn’t changed. But what did change was my sense of responsibility.

When an opportunity of this scale comes your way, there’s only one thing playing on your mind-you have to give it your absolute hundred percent, every single day. As actors, we’re constantly waiting for that one right opportunity, and for me, this was it. The biggest opportunity of my career so far.

I didn’t want to leave a single stone unturned. I didn’t want to disappoint anyone-especially Aditya sir, who had placed so much faith in me. He believed in me, and breaking that trust was never an option. So I made sure I was completely prepared-emotionally, mentally, technically. I did all the homework, stayed alert to every detail, and then, in a way, surrendered it all to the Almighty. I knew I had given my best. Beyond that, some things are not in your control.

That dedication translates powerfully on screen. Your performance carries a certain conviction that lingers. How does it feel now that the audience has embraced Uzair Baloch so wholeheartedly?

I feel extremely blessed. When you work with complete honesty, all you hope for is that it reaches the audience-and that they feel something. When they respond with love, it feels like a victory.

But it’s not just my victory. It validates the faith of everyone involved in the film-the director, the writers, the entire team. That collective validation is incredibly fulfilling.

Uzair Baloch is inspired by a real, living, and deeply controversial figure. How did you navigate the ethical and emotional challenge of humanising someone associated with extortion and violence, without slipping into glorification?

That balance was largely shaped by Aditya sir. He knew the narrative inside out-the script, the arc, the moral boundaries of the character. From our very first meeting, he was clear about who Uzair was and, just as importantly, who he wasn’t.

He gave me extensive research material-interviews, references, context-to understand the world Uzair came from. I studied his life, his public persona, and realised very quickly that this was an entirely different universe from my own. Danish and Uzair exist in two completely separate worlds.

For an actor, that’s actually the most exciting part-stepping into someone else’s shoes, understanding their psychology, their emotional landscape. More than emotional turmoil, it was a deeply engaging process for me.

Initially, in the first few days, you’re still finding the rhythm of the character. But gradually, the character starts guiding you. You stop asking what Danish would do, and start responding to what Uzair would do. His choices, his silences, his aggression-it all begins to flow organically.

Even something as basic as the way he speaks became crucial. My natural speech pattern is very different from Uzair’s, and that vocal shift helped draw a clear line between the real person and the character.

What truly felt like a personal victory was when people close to me-friends who know me intimately-watched the film and told me they never saw Danish on screen. They only saw Uzair. Not even for a moment did they feel it was me. For an actor, that’s everything.

One of the most discussed moments in Dhurandhar is the 26/11 sequence, especially because it blurs the line between cinema and collective national trauma. As an Indian actor portraying a Pakistani character reacting to an attack on India, did you experience any internal conflict during that scene? And how did you consciously separate Danish the individual from Uzair the character?

Also, given how emotionally charged that moment was-you’ve spoken about hugging Ranveer Singh after the take-how taxing was that scene for everyone involved?

If you look at that particular scene, almost every major character is present in that room-Major Iqbal Rehman, David Headley, Hamza, Uzair, Azam G Man. It wasn’t just a performance-heavy sequence; it was emotionally dense for everyone involved.

Before we even began shooting, we were made to listen to the actual audio-the conversation between the handlers and the terrorists. Hearing it for the first time is deeply unsettling. As an Indian, and as someone who is immensely proud of his country, it hits you in the gut.

When 26/11 happened, most of what we knew came through media coverage. We didn’t fully understand what was unfolding inside those spaces-the mindset of the handlers, the conversations they were having, the cold calculations behind the chaos. Listening to those recordings, knowing the reality of what people were going through inside-bullets firing, panic, fear-it was incredibly disheartening. You feel disturbed. You feel helpless. And above all, you feel a surge of empathy for the victims.

But as an actor, you’re also painfully aware that your character doesn’t allow you that emotional indulgence. For a brief moment, the human in you reacts-but then you have to switch it off. Uzair doesn’t respond as Danish would. The second you allow your personal emotions to take over, the character collapses. So you have to step back and observe everything from a third-person lens, staying true to the psychology of the role.

That’s why Hamza Ali Mazari’s close-up in that scene was so powerful. When the camera lingers on his face, especially on his eyes, you see the emotion that every Indian in that room-and watching the film-was feeling. His eyes carried the grief, the shock, the rage, the helplessness. Sitting at the monitor and watching that shot unfold, I felt completely shattered.

It took him a while to come out of that zone. I remember going up to him and just hugging him because he was still processing it. At the same time, he had to immediately shift gears for the next moment-when Major Iqbal turns around and continues the conversation. That balance-being internally broken yet outwardly functional-was incredibly demanding.

ing that unfold, I realised how profoundly he had channelled the collective emotion of an entire nation. He wasn’t just playing a character; he was carrying the weight of what millions felt in that moment. And being present for that, witnessing it up close, was deeply affecting for all of us.

There’s been a lot of conversation around Ranveer Singh and Sara Arjun’s chemistry in the film, but I was equally struck by the dynamic between Uzair and Hamza. There’s a raw, almost understated intimacy there-even in high-octane moments like the gunfire sequence in the valley, where you’re blazing guns together. How organic was it to build that bond with Ranveer, and how did your off-screen equation evolve as the shoot progressed?

We began shooting around July last year, and most of my scenes were with Ranveer bhai. I still vividly remember the very first day of the narration. He came up to me, hugged me, and said, “Danish, we’ll kill it.”

For a superstar of his stature to offer that kind of warmth and reassurance-it makes a world of difference. Ranveer is someone who makes people feel important. He motivates you, inspires you, and carries this incredibly positive, contagious energy. He’s secure, selfless, and deeply generous as a co-actor-qualities you always hope for when sharing screen space with someone so experienced.

He’s also an exceptional listener. Our dynamic was built on constant banter and reciprocation-being receptive to each other in every moment. Even though I had done my homework and was conscious of not wanting to disappoint my senior actors, Ranveer made the environment so comfortable that the journey felt smooth, almost effortless.

If you observe the film closely, you’ll notice how our chemistry builds gradually, very organically. The valley gunfire sequence you mentioned-where we’re firing together-is a complete adrenaline rush. Moments like that elevate the bond between characters. It creates that unspoken understanding of “I’ve got your back.”

Ultimately, that chemistry is the result of multiple things coming together-the script, the screenplay, Aditya sir’s execution, and a co-actor who approaches the process with such openness and emotional security.

I want to take you back to another unforgettable moment-the Babu Dakait sequence. That image of Akshaye Khanna smashing a weighing stone onto a man’s head is brutal and deeply unsettling. Aditya Dhar is known for grounding violence in realism rather than spectacle. How did that sequence come together creatively? And if I’m not mistaken, this was shot in Thailand?

Yes, that sequence was shot in Thailand. And you’re absolutely right-Aditya sir is a very sharp and responsible filmmaker. He doesn’t use violence to excite the audience or glorify brutality. With him, violence always has a context, an emotional grounding, and most importantly, a consequence.

In Dhurandhar, violence is never meant to be cheered for. It’s meant to be understood. It’s about the psyche of the character-what they’re going through at that moment, and why they’re capable of crossing that line. Every act of violence in the film is a culmination of the script demanding it, not the other way around.

There’s a thin line between using violence as a storytelling tool and romanticising it. Aditya sir is very clear about where he stands. He’s not interested in shock value. He’s interested in character arcs. In this case, the brutality comes from a deeply personal place-Babu Thevar has lost his son. There’s rage, grief, and a long-simmering tension that has been building through earlier conversations and confrontations.

Cinema can’t always be softened for convenience, especially when realism is at play. When a script is rooted in truth, it has to reflect the harshness of that world. The backstory of the characters, the environment they come from, and the immediacy of the situation-all of it feeds into moments like this.

So that sequence isn’t about glorifying violence at all. It’s about showing what the situation demanded at that precise moment. And that sensitivity-that sense of responsibility-is what makes Aditya sir such a compelling storyteller.

You were also the first to reveal that Akshaye Khanna’s dance in “FA9LA” was completely impromptu. There’s another moment during Shararat where his character suddenly breaks into dance, and it feels just as spontaneous and genuine. Was that improvised as well?

Yes, it was. There was already a dance sequence happening, and we were meant to greet Hamza and Sara on stage. But what Akshaye sir did in that moment came purely from how the character was feeling.

If you look at Rehman across the film, he’s a man of very few words. He’s restrained, measured, almost closed-off. But at the end of the day, he’s still human. He feels joy. He wants to celebrate. And in that moment, someone from his own gang is getting married-there’s happiness, relief, a rare sense of lightness.

That sudden burst into dance wasn’t about choreography; it was an emotional expression. It was his way of saying, I’m happy, without saying anything at all.

Interestingly, I recently watched Vijay Ganguly’s interview where he spoke about this scene. While editing, he felt the moment needed a signature movement-and when he saw what Akshaye sir had done organically, he immediately understood that this was the moment. Even as a choreographer, he recognised what the character was trying to communicate emotionally. It was exactly what the scene demanded.

The film has also sparked intense conversations-fan theories about a possible Part Two, debates around Hamza and Uzair’s trajectories, and at the same time, accusations of propaganda from certain sections. How do you view this sharp divide in opinion? Do you feel some of the criticism comes from vested interests?

Honestly, the film was made purely from a storytelling perspective-not to push a message or agenda. And audiences today are very smart. They can choose to agree, disagree, question, or even reject something-and that’s absolutely fair.

Once a film is presented to the world, we as filmmakers lose control over how it’s interpreted. Some people may view it through a political lens, others through an emotional one. Filmmaking is inherently subjective. You might agree with a certain perspective, I might not-and that’s okay.

But if you look at Dhurandhar at its core, it’s about narrative, not messaging. We’re not forcing an opinion on anyone. We’re simply telling a story and allowing viewers to feel what they feel.

It’s been nearly three weeks since the film’s release, and the overwhelming response has been love. I personally haven’t encountered accusations of propaganda in any meaningful way. And that itself speaks volumes.

Audiences today are intelligent-they know when something is dishonest and when it’s rooted in sincerity. The fact that the film is being embraced so strongly tells me that people are connecting with the storytelling, the realism, and the cinematic experience Aditya sir has crafted after years of research and writing. That, to me, is truly commendable.

There have also been comparisons between Dhurandhar and larger-than-life spy spectacles like Pathaan or Tiger-with many pointing out that those films are glossy and stylised, while Dhurandhar is gritty and grounded. Do you think both approaches can coexist, or should filmmakers begin leaning more towards the Dhurandhar model?

I absolutely believe both approaches can-and should-coexist. Cinema is a deeply subjective experience. Some audiences prefer stylised spectacle, others gravitate towards realism. Neither is right or wrong.

What matters most is that films continue to be made and experienced on the big screen. Cinema is one of the most beautiful, community-driven mediums we have. You go to a theatre with family or friends, you share an experience, you build memories. That ecosystem is incredibly important.

When one film works, it motivates other filmmakers to tell more stories. It creates employment. It sustains livelihoods. Hundreds of people come together to make a single film-and that ripple effect matters.

For actors like us, it also opens doors to explore different characters, different worlds, different emotional landscapes. Every filmmaker has a unique voice, a different way of telling stories, and that diversity is what keeps cinema alive.

As long as a film is being loved by audiences, it’s relevant. Whether it’s grounded or stylised, gritty or glossy-there’s space for everything. What’s important is sincerity in storytelling. Cinema should continue to inspire imagination, provoke thought, and transport audiences. That’s the magic of the medium-and that’s why all these approaches deserve to coexist.

Music plays a crucial role in Dhurandhar. It never feels like a placeholder-whether it’s Ramba Ho during the shootout or Piya Tu underscoring the bike chase. How involved was Aditya Dhar in shaping the film’s musical narrative on set?

Aditya sir is deeply, thoroughly involved-right down to the smallest detail. As the captain of the ship, he doesn’t overlook anything. Music, for him, isn’t an add-on; it’s an extension of storytelling.

You can see that in how audiences are reacting. People aren’t just talking about the action-they’re talking about how the songs and background score elevate those moments. The music completely changes the emotional texture of a scene.

Take the climax, for instance-when Hamza and Rehman confront each other and the title track kicks in. The impact is something else altogether. It gives you a surge you can’t quite explain-it’s visceral.

That’s the beauty of it. When every element-sound, performance, action, emotion-comes together seamlessly, it feels like a perfectly executed symphony. And Aditya sir is involved in every note of that symphony.

I recently watched Vijay Ganguly’s podcast, where he spoke about the Shararat song. He mentioned suggesting Tamannaah Bhatia for it, and Aditya sir’s response was telling. He said he wanted to stay focused on the narrative-on what the story needed at that point-rather than getting distracted by star value or spectacle.

That’s how invested he is in storytelling. Interestingly, while we were shooting that sequence, our attention was entirely on what was happening at the dining table-because that’s where the emotional shift occurs. The diary falling changes the course of the entire film from that moment on. Everything else, including the song, was in service of that narrative pivot.

Aditya Dhar’s films also have an uncanny ability to seep into pop culture-organically. From Uri’s “How’s the Josh?” to Dhurandhar now spawning memes and real-life trends, what do you think is the secret behind this kind of cultural resonance?

It comes from his sheer love for cinema. He’s a true film buff-obsessively passionate about his craft. He’s watched Shiva by Ram Gopal Varma at least 13 or 15 times. That tells you everything.

He watches films constantly-across languages, across cultures. He understands world cinema deeply. And when someone has spent years immersing themselves in movies, studying them, absorbing their rhythm and grammar, that understanding naturally reflects in their own work.

He doesn’t chase moments for the sake of trendiness. He stays true to his intent. And when you do that honestly, those moments organically find their way into pop culture.

Aditya sir is a very sharp filmmaker. He understands nuance-of screenplay, of character arcs, of emotional beats. Look at how he builds even the so-called “supporting” characters. Take Donga, for example. He’s one of the gang members, yet his character is so well-established that people remember him vividly.

Naveen is such a fine actor-we’ve seen him in Rocket Singh, we’ve seen his theatre work-and Aditya sir gives him that space, that stature. Even his appearance in the climax carries weight. That’s intentional.

Character recall is everything. If people remember your character after the film ends, you’ve done something right. And in Dhurandhar, almost every character has a distinct arc, a clear presence.

That’s why the film is slowly achieving a kind of cult status. People aren’t just talking about the leads-they’re talking about Donga, about the gang, about these smaller yet impactful roles. And all of that comes down to a tight, meticulously crafted screenplay.

For that, the credit has to go to Aditya sir. His writing, his research over five years, and his absolute commitment to realism-that’s the true backbone of Dhurandhar.

Speaking of Dhurandhar 2, the teaser hints at a much darker turn for Uzair-especially that striking image of him committing murder with a cleaver. Without giving too much away, what can audiences expect from Uzair going forward? And does the power dynamic shift now that Rehman is no longer in the picture?

I can honestly say only one thing-Uzair knows exactly what he’s doing. Danish, on the other hand, I know nothing about what lies ahead.

I genuinely have no clue what Uzair is up to. And I think that’s the point. Whatever answers exist will unfold on March 19. Even I’m excited as a viewer to see what’s in store. I don’t know what’s going to happen-and that uncertainty is thrilling.

Looking at the bigger picture, what does a film like Dhurandhar signify for the future of Indian cinema? Do you see it as a cultural milestone-something people might one day refer to as pre-Dhurandhar and post-Dhurandhar?

That’s a beautifully framed question. Cultural milestone is a very strong term-and while many people have been saying that, I want to be a little careful.

Maybe people are being kind because I’m part of the film. But what’s undeniable is the kind of word-of-mouth the film has generated. It didn’t explode overnight-it grew steadily, organically. And that’s the most powerful kind of success.

You meet people on the street, and there’s genuine affection for the film. That’s an incredibly proud feeling for all of us. It feels like a collective victory.

Personally, I wouldn’t call it a cultural milestone just yet. That would mean redefining the entire cinematic landscape. But what I would say-very confidently-is that Dhurandhar has created a benchmark. A new standard.

And that, in itself, is something to be deeply proud of.

When people look back at your career ten years from now, what would you rather they say-he made it or he changed something?

I’d probably put it differently. I’d say it’s an ongoing journey-one driven by fulfilment.

For me, it’s not about changing something or proving that I’ve arrived. It’s about creative satisfaction. About staying honest to the process, following the journey with the right intent, and continuing to grow as an actor.

If that journey feels fulfilling-emotionally and creatively-that’s enough.

Finally, what’s next for you? What can audiences expect to see you in after Dhurandhar?

I do have a couple of things lined up, and I’ve already completed shooting for one of them. But at this point, I can’t really talk about it.

Hopefully, sometime in the future-if I get the opportunity to speak with you again-I’ll be able to share more. I’d love that.