When Ashutosh Gowariker’s Lagaan (2001) – starring Aamir Khan, who is currently basking in the buzz around Sitaare Zameen Par – was first announced, the idea of a nearly four-hour period film about cricket set in colonial India, with British officers as antagonists and villagers as players, was met with a lot of scepticism, including from its lyricist Javed Akhtar.

Cricket, though a national obsession and considered to be a religion unto its own, wasn’t considered cinematic in a conventional sense, and there were real concerns about whether audiences would turn up for a film that combined sport and history without a clear romantic or action-driven core.

But Lagaan, centred on the locals beating the Brits in the gentleman’s game to get rid of the double lagaan (tax) imposed on them by the Raj, redefined the structure of the sports drama by situating the match within the larger politics of power and resistance, drawing viewers into not just its outcome, but the dynamics between figures of colonial authority and the ordinary people subject to it. Lagaan succeeded not just commercially – becoming one of the highest-grossing films of its time and earning an Academy Award nomination – but conceptually, proving that even a sports film could take on serious themes like colonialism while still holding an audience’s attention across languages and regions.

Aamir Khan’s latest film, Sitaare Zameen Par, is an official remake of the Spanish comedy Champions.

Aamir Khan’s latest film, Sitaare Zameen Par, is an official remake of the Spanish comedy Champions.

Its unmistakable underdog spirit resonated with both audiences and critics at the turn of the century. Critics in India and abroad raved about it. “Lagaan is a lavish epic, a gorgeous love story, and a rollicking adventure yarn. Larger than life and outrageously enjoyable, it’s got a dash of spaghetti western, a hint of Kurosawa, with a bracing shot of Kipling…. Ashutosh Gowariker’s film is virile, muscular storytelling, with rich musical dance numbers, and inspired touches like an Untouchable inventing off-spin…” wrote Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian.

By the mid-2000s, Hindi sports dramas veered towards gender and national identity. Chak De!India (2007), directed by Shimit Amin, known for Ab Tak Chhappan (2004) and Rocket Singh: Salesman of the Year (2009), told the story of Kabir Khan, a disgraced former hockey captain (Shah Rukh Khan). Accused of bringing dishonour to his country in a global hockey tournament, he unites India’s women’s team to win the World Cup. Released on Independence Day, the film was soaked in patriotic fervour.

The film smashed expectations at the box office, earning roughly Rs 109 crore, and became one of the year’s biggest hits. “…Amin… strikes a buoyant, propulsive tone, replacing the customary Bollywood production numbers with exhilarating musical montages of team practice. For his part, Mr. Khan, to his credit, lets his co-stars’ youthful charisma carry the movie. He also laudably portrays a man who vigorously and unabashedly advocates the advancement of women. In fact, the film’s greatest merit is its commentary on sexism in India. As it should, “Chak De! India” gives the women, in the closing credits, the last word,” Andy Webster wrote in his review in The New York Times

In retrospect Chak De! is seen as a ‘cultural phenomenon,’ credited with sparking conversations about women in sport. Like Weber, another reviewer noted its explicitly feminist themes, praising both SRK’s performance and its screenplay. Its song, Chak De India (Jaideep Sahni’s words, composed by Salim-Sulaiman and sung spectacularly by Sukhwinder Singh, Salim Merchant and Marianne D’Cruz), became an anthem of sorts.

In retrospect Chak De! is seen as a ‘cultural phenomenon,’ credited with sparking conversations about women in sport.

In retrospect Chak De! is seen as a ‘cultural phenomenon,’ credited with sparking conversations about women in sport.

In the years that followed, real-life sports biopic became a formula for many filmmakers. Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) dramatised the life of Milkha Singh, also known as ‘The Flying Sikh’, the only athlete to have won gold at 400 metres at the Asian Games as well as the Commonwealth Games; he represented India at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. With Farhan Akhtar essaying the role, the film struck a chord with most of us. It became the year’s sixth highest-grossing film. Globally, it raked in over Rs 210 crore.

“The smart, sinewy Akhtar does not look like the typical Bollywood hero, which is one of the factors that Mehra says led him to choose him for the role after a casting search that took him as far as Canada, the UK and the US. He trained hard for a year and a half before the start of shooting, including a regimen in mountainous Ladakh at 14,000 feet. But beyond the impressive physique he has cultivated for the role, Akhtar has captured a sense of focus and piety that led Singh to rise from his humble beginnings as a post-Partition refugee and small-time crook to national champion,” wrote Lisa Tsering in The Hollywood Reporter.

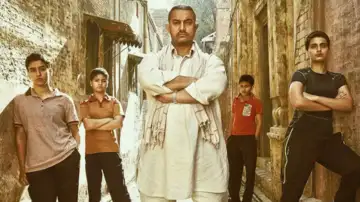

Three years later, Nitesh Tiwari’s Dangal took the biopic trend further. Based on wrestler Mahavir Singh Phogat and his daughters, it tackled patriarchy head-on: Mahavir trains his reluctant daughters Geeta and Babita to become world-class wrestlers, bucking family and caste expectations in Haryana. Aamir Khan’s film was a juggernaut, eventually grossing Rs 2,024 crore worldwide and winning acclaim as the highest-grossing Indian film of all time.

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) dramatised the life of Milkha Singh, also known as ‘The Flying Sikh’.

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) dramatised the life of Milkha Singh, also known as ‘The Flying Sikh’.

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) dramatised the life of Milkha Singh, also known as ‘The Flying Sikh’

Critics lauded its truthful portrayal of female empowerment; the Los Angeles Times noted how the film “bursts with purpose and pride” as it celebrates sisters Geeta and Babita’s unlikely championship. Aamir himself expressed hope that Dangal would “change perception” in India about girls in sport, and the box office proved the hunger for such stories.

Aamir had hoped that Dangal would “change perception” in India about girls in sport, and the box office proved the hunger for such stories.

Aamir had hoped that Dangal would “change perception” in India about girls in sport, and the box office proved the hunger for such stories.

Meanwhile, Mary Kom (2014) brought another strong woman’s story to the fore. This biopic of the Manipuri boxer Mary Kom highlighted both gender and ethnic marginalisation. It was a commercial hit (earning around Rs 86 crore domestically on a moderate budget) and critics praised Priyanka Chopra’s fiery performance. The film touched on Kom’s struggles as a mother and athlete from the Northeast, which has often been underrepresented in mainstream Hindi cinema. Both Dangal and Mary Kom moved beyond the lone male hero trope: women were now leads in the action, and their stories exposed the deeply rooted, systemic biases.

Kai Po Che! (2013), adapted from Chetan Bhagat’s The 3 Mistakes of My Life and directed by Abhishek Kapoor, used cricket as a backdrop to explore communal strife. It follows three friends in Gujarat (Amit Sadh, Sushant Singh Rajput, and Rajkummar Rao) who run a cricket academy even as the 2001 earthquake and the Godhra riots tear their community apart. It struck Indian critics as “a well-crafted, engaging drama that makes its point without sinking into preachiness”. On a Rs 30 crore budget, it earned about Rs 83 crore worldwide, and five Filmfare nominations. In effect, Kai Po Che! showed that a sports film could tackle politics, too; the game of cricket in the film intersects with religion and regional identity.

Other sports dramas like Anurag Kashyap’s Mukkabaaz (2018) brought class and caste conflict into the ring. A gritty tale set in rural Uttar Pradesh, it follows an aspiring boxer denied by local elites. Kashyap intentionally wove a love story – the boxer’s romance with the Federation chief’s niece – into an indictment of corruption and caste bias in sports. Critics immediately noted its ambition. Anupama Chopra wrote that Mukkabaaz interlaced an underdog sports tale with a “scathing critique of corruption in Indian sport [and] the caste system”.

In the same vein, Jhund (2022), starring Amitabh Bachchan, zeroed in on poverty and social mobility. Directed by Marathi auteur Nagraj Manjule, it fictionalises the life of Vijay Barse, founder of Slum Soccer. Bachchan plays a retired teacher who starts coaching slum children in Nagpur to play football. The film’s USP is how it tackles caste and class issues without melodrama. Critics saw it as more than a standard sports story. Saibal Chatterjee wrote how it “upends the Bollywood sports biopic template… to craft an incisive and deeply felt commentary on the reality of systemic oppression”. The movie shows literal and figurative walls that keep marginalised youth from opportunity, aligning their struggle with Bachchan’s own past.

The sports dramas have often returned to cricket, but each film has brought something different to the table. Nagesh Kukunoor’s Iqbal (2005) is a heartfelt story of a deaf and mute boy determined to become a cricketer, coached by an unlikely mentor. In 2007, Goal explored cricket through the lens of a training academy, while Chain Kulii Ki Main Kulii used the sport to tell a wish-fulfilment tale of a boy who discovers a magical bat. Ta Ra Rum Pum, also from 2007, switched lanes entirely and focused on Formula One racing, making it one of the few Hindi films to dive into motorsport.

The same year saw Hattrick used cricket as a backdrop to look at love, illness, and national obsession. Victory (2009) returned to cricket again, showing the pressures of fame and the fallout of bad choices. Films like Meera Bai Not Out (2008) and Stumped (2003) treated cricket as a social glue, part of everyday life and conversation. Hawaa Hawaai (2014) stood out for picking roller-skating, following a young boy’s dream and how his coach helped him rise despite poverty and poor nutrition. Saala Khadoos (2016) took on boxing, with a fierce coach training a girl boxer while fighting a corrupt federation. On the darker side of sports, Jannat (2008), 99 (2009), World Cup 2011 (2011), and Azhar (2016) all focused on cricket’s biggest scandal – match-fixing-and how greed and pressure can drag the game and its players down.

In Shabaash Mithu (2022), based on the life of Mithali Raj, India’s cricket captain, Taapsee Pannu plays yet another physically rigorous role. But the film doesn’t go for the “girl power” aesthetic and focuses instead on humiliation: Forgotten kits, empty stadiums, pat-downs by male staff at airports. In short: the institutionalised invisibilisation of women in sport.

Last year, Sharan Sharma’s Mr & Mrs Mahi drew on MS Dhoni and Sakshi Dhoni’s love story though the director has reiterated it doesn’t. In the film, a failed cricketer (Rajkummar Rao) discovers his wife’s talent (Janhvi Kapoor, as an accomplished bowler) and becomes her coach. The Guardian praised it as a “small monument to partnership building,” noting that Rao’s character finally “pivots to coaching and nudges his wife towards the spotlight”. It was a moderate success (crossing Rs 35 crore), but in a country where women’s roles often remain circumscribed, a film showing a husband fully backing his wife’s career was a subtle way to challenge old norms.

2024 also saw the release of Maidaan, an ambitious biopic of football coach Syed Abdul Rahim, starring Ajay Devgn. Produced on a big budget (reportedly Rs 250 crore), it aimed to celebrate India’s “golden era” of football in the 1950s. The film is vintage underdog – rebuilding a demoralised national team to win the Asian Games – but it also carries the strands of nationalism and nostalgia. Sadly for its creators, Maidaan earned only Rs 68 crore against its cost. Critics were mixed: some applauded its scale and period detail, but others felt the script lacked the intimacy of earlier sports films.

Aamir Khan’s latest film, Sitaare Zameen Par, his first sports film in over a decade which makes us rethink our ideas of what is normal, is an official remake of the Spanish comedy Champions. Khan plays a hot-tempered basketball coach sentenced to train a team of players with intellectual disabilities as community service. Reviewers have written how the film deliberately dissolves the star’s ego. One observer wrote that Khan “ditches the halo and dons humility, letting the real stars – his neurodivergent team – shine brightest”. In other words, the film is about the players more than the coach. This marks Sitaare… as an especially inclusive story.

Sitaare Zameen Par confronts yet another social blindspot in Bollywood: disability. As one critic noted, few mainstream Hindi films tackle this subject. Indeed, praising the film as “entertaining and edifying,” Filmfare observed that Sitaare Zameen Par “teaches while it entertains, without ever being preachy,” and “nudges us to be kinder, gentler, and more accepting”. The movie opened to Rs 19.5 crore globally on day one and went on to earn over Rs 200 crore in two weeks. Its success suggests audiences are not just looking for thrills on the field, but also resonance off it. What stands out, looking back at the over two decades of Hindi sports films, is not just the diversity of sports – cricket, hockey, boxing, racing, football, wrestling, roller-skating, even basketball – but the steadily widening emotional and political range of the stories being told.