It is generally assumed or expected that a country’s stock market performance should be positively correlated with its GDP growth.

Thus, if a country is doing well on the growth front, its stock market should do well. Similarly, growth slowdown should lead to corrections in stock market indices, for instance the Sensex or the Nifty 50.

Most equity analysts opine that the single most important driver of stock market performance is actual or expected changes in corporate earnings, and economic expansion (in contrast to economic contraction) that positively affects earnings and in turn, share prices. It would be interesting to analyse if this hypothesis applies to India.

Looking at time series data about the performances of the US GDP and S&P 500 shows that there is a positive correlation between the two, except during the pandemic and other major crises such as the Great Depression or the Dotcom (2000) burst. The S&P 500 gave decent returns during the pandemic even though the US economy tanked, primarily because of the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus. Something similar happened in many other markets including the EU and India.

But in the case of China, despite robust GDP growth on a consistent basis between 1999 and 2019, there have been wild swings in the performance of its stock markets. For instance, the Shanghai Composite (SHCOMP) Index witnessed massive gains in some years and poor returns in others. Moreover, the returns on SHCOMP during the Covid years had been unimpressive vis-a-vis India, EU and the US.

The Indian Evidence

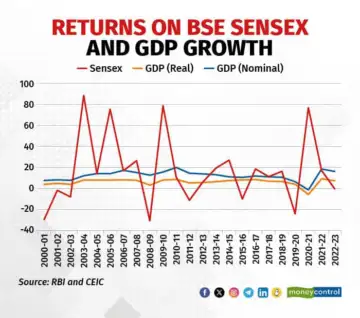

As shown in the above chart, the correlation between the performance of the Indian economy as measured by its GDP growth and the Sensex is not strong, and this has been more so in the last couple of years.

One would want to argue that stock markets are forward-looking and driven by expectations about how the economy will perform. If investors believe that a country’s GDP will grow in the future, they may buy stocks in anticipation of higher corporate profits even though the current GDP numbers are not good. This is especially so after the Indian government slashed corporate income tax in September 2019, which has led to an increase in the share of corporate profits in the country’s GDP.

Nevertheless, corporate earnings don’t provide the full picture, at least in India’s case. Global developments, for instance the US Fed’s actions and unexpected swings in crude oil prices strongly influence Indian stock market prices even though there is no real change in the domestic economic output or its outlook. Amidst sticky inflation and the rupee (almost always under pressure), interest rate hikes by the US Fed affect Indian stock markets in two ways – through increasing interest rate differentials between India and the US (thereby improving the relative attractiveness of US bonds), and by putting pressure on the RBI to go hawkish, that tends to penalise interest rate sensitive sectors such as automotive, banks, infrastructure and real estate, metals as well as companies with high debt-to-equity ratios (irrespective of sectors) which have substantial weights in the Sensex and Nifty 50.

The inflows from foreign institutional investors (FIIs) have been playing a major role in influencing stock prices in India. However, their actions are guided by factors which are mostly outside the control of Indian policy makers, for instance, US Fed actions (as mentioned above), and actual or expected performance of other economies in the region such as China. The moves of FIIs can also be influenced by changes in relative valuations of stock market indices of different countries competing for foreign capital. Thus, the FIIs may start selling in overvalued markets like India and that will drive down stock prices even if there is no change in the country’s economic growth outlook. Movements in exchange rates also tend to influence such decisions.

However, of late, steadily increasing participation from retail investors either directly or through mutual funds has reduced the influence of FII flows. The absolutely and relatively low penetration of financial products, equity and equity-based mutual funds, in particular, means that there would be faster deployment of retail money especially when the stock markets are on the upswing.

Similarly, stringent limits on Indians buying shares of companies listed abroad through the LRS (Liberalised Remittance Scheme), the $ 7 billion cap and unfavourable taxation force Indians to allocate a higher proportion of their capital in Indian stock markets. That provides an additional support to the country’s equity market.

Too Many Variables

Given India’s excessive dependence on import of crude oil and substantial weights of oil and gas companies in benchmark indices, any unexpected surge in global energy prices may lead to sell off of shares of energy companies by both domestic as well as foreign investors leading to correction in their share prices and in turn in Sensex and Nifty 50.

Even otherwise, different sectors within an economy may respond differently to GDP growth. Some sectors, such as consumer discretionary, may be more sensitive to economic expansion, while defensive sectors such as consumer staples or pharmaceuticals may be less influenced by short-term fluctuations in GDP growth.

On a longer term basis, political stability encourages business activities and strengthens investor confidence. That is good for stock markets. On the other hand, regulatory flip-flops and knee-jerk reactions to major macroeconomic challenges such as sticky inflation or worsening trade deficits dampen the profitability prospects of companies in the affected sectors and in turn their stock market performances, often independently of GDP growth. Thus, stringent export curbs on rice, steel and sugar, aimed at reining in inflation have ended up adversely affecting the top and bottom lines of companies operating in these sectors leading to corrections in their share prices. Similarly, import curbs aimed at reducing trade deficit and supporting the rupee have led to increased costs for companies engaged in retailing and dampened their stock market prospects.

At present, the geopolitical sweet-spot and the China plus one strategy is favouring all kinds of manufacturing companies in India and in turn aiding their stock prices that have no immediate connection to the country’s economic growth.

Last but not the least, human psychology plays a major role in stock markets by affecting investor sentiments. Thus, excessive fear – caused by economic factors such as runaway inflation or sharp increases in tax rates, and non-economic factors such as a deadly pandemic or wars may lead to sell-off irrespective of how an economy is doing and thus override the fundamental relationship between GDP growth and stock prices.

To sum up, it’s essential to recognise that while there is a historical tendency for stock markets to perform well in growing economies with reasonable macroeconomic stability, the correlation is not perfect, especially for a country like India as many other variables including difficulty to predict human psychology, tend to influence investor behaviour, and in turn returns on stock market investments.

Then there could be variations in sectoral performances. For instance, the performance of India’s banking and financial sector as measured by the Nifty Bank index doesn’t really reflect the robust earnings reported by banking and financial companies vis-a-vis infrastructure companies for instance, in the last couple of quarters. Moreover, despite sharp contractions in India’s GDP growth rates during Covid, its stock markets have delivered one of their best returns in decades.