Excerpted from the essay ‘The Militarized Zone’ by Angana P. Chatterji, from Kashmir: The Case for Freedom by Tariq Ali, Hilal Bhat, Angana P. Chatterji, Habbah Khatun, Pankaj Mishra and Arundhati Roy (Verso Books, 2011).

This is in the union territory by the Jammu and Kashmir home department.

Srinagar, 9 January 2011. Amid the disquiet of winter, I listen to torture survivors recounting their life stories. ‘I am neither a stone-pelter nor a politician. I protest unfreedom,’ Bebaak tells me. Now nineteen years old, he participated in street protests in the summers of 2009 and 2010. ‘The police said I would be arrested unless I stopped going to rallies. Then the police filed a First Information Report against me because I protest. What are the charges? That I refused subjugation?’

In 2010, Bebaak was detained for more than ten days, in violation of habeas corpus. While in custody, he was tortured: struck repeatedly and violently and denied medical treatment. Other youths in custody at that time were water-boarded. Some were forced to remove their clothes, then threatened with sodomy.

Officials attempted to coerce Bebaak into admitting that he had thrown stones and destroyed police property. Refusing to admit to crimes he had not committed, Bebaak was locked up in isolation, where he was beaten again. He recounts how, taking turns, two officers held him down while a third struck him with a baton, the butt of a rifle, and an iron chain: ‘They only stopped when they were tired.’ Bebaak and other youths I speak with testify that the physical attacks were accompanied by verbal abuse: ‘Your “race” is deranged. You are criminals. You are thieves. Your mother is a whore. Your sister will be raped by your people who are crazed. You will never see azadi.’ ‘In the jail, in the dark, as I lose consciousness’, Bebaak says, ‘I think, “We Kashmiris are a people, not a race. Our struggles against India’s brutalities do not make us criminals.” ‘

…

Tariq Ali, Hilal Bhat, Angana P. Chatterji, Habbah Khatun, Pankaj Mishra and Arundhati Roy

Tariq Ali, Hilal Bhat, Angana P. Chatterji, Habbah Khatun, Pankaj Mishra and Arundhati Roy

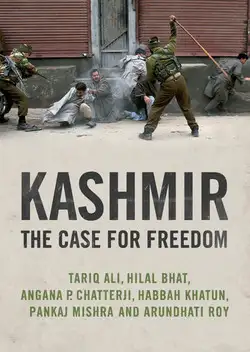

Kashmir: The Case for Freedom

Verso Books, 2011

Each dimension of life in India-governed Kashmir is replete with the obsessions and absurdities of militarization. Every street, neighbourhood, public building and private establishment, forest and field, and road and alleyway has been ‘securitized’. The overwhelming presence of the military, paramilitary, and police, of their guns and vehicles, of espionage cameras, interrogation and detention centres, of army cantonments and torture cells, orders civilian life. Kashmir is a land- scape of internment, where resistance is deemed ‘insurgent’ by state institutions.

Later that day, I meet Khurram Parvez at our office at Lal Chowk. Khurram is a human rights defender, an amputee who lives with the daily targeting that ethical dissent begets. ‘We make choices in living in Kashmir,’ he says. ‘To be silent when people are being brutalized is refusing to take responsibility. It is our moral obligation to take responsibility, to resist in principled ways.’ Responsibility requires we bear witness as a call to action.

The word freedom represents many things across India-ruled Kashmir. But these divergent interpretations are steadfastly united on one point: freedom always signifies an end to India’s illiberal governance. In the administration of brutality, India, the former colony, has proven itself equal to its former colonial masters. Governing Kashmir is about India’s coming of age as a power. Kashmir is the result of a fixation with haphazard and colonially imposed borders. India overwrites memory – histories of violence, conflict, partition, and events that remain unresolved – to maintain the myth of its triumphant unification as a nation-state with Kashmir at its headspring. India’s control of Kashmir requires that Kashmiri demands for justice be depicted as a threat to India’s integrity.

Marshalling colonial legacies, the post-colonial state seeks to consolidate the nation as a new form of empire, demanding hyper-masculine militarization and territorial and extra-territorial control. This requires the manufacture of internal and external enemies to constitute a national identity, constructed in opposition to the anti-national and non-native enemies of the nation.

Hindu majoritarianism – the cultural nationalism and political assertion of the Hindu majority sanctifies India as intrinsically Hindu and marks the non-Hindu as its adversary. Hindu majoritarian culture has been consolidating its power despite the interventions of secular, syncretic, and progressive stakeholders. Race and nation are made synonymous in India, as Hindus – the formerly colonized, now governing, elite – are depicted as the national race… India’s political and media establishments caricature the Kashmiri Muslim as violent, impure, anti-national, as one who does not belong and who has refused political, cultural, and economic assimilation. The Kashmiri, historically residing outside the present Indian nation, is branded ‘seditious’ for seeking a different self-determination, for not belonging, and for not accepting annexation.

…

I spent considerable time between July 2006 and January 2011 learning about and working in Kashmir, making sixteen separate trips to the region. In July 2006, the noted human rights lawyer Parvez Imroz invited me to collaborate in instituting the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in India-administered Kashmir, which we convened on 5 April 2008, together with Zahir-Ud-Din, Gautam Navlakha, Mihir Desai, and Khurram Parvez.

In undertaking work for the Tribunal, I have travelled through Kashmir’s cities and countryside, from Srinagar to Kupwara, through Shopian and Islamabad/Anantnag. I have witnessed the violence that India’s military, paramilitary, and police perpetrate against Kashmiris. I have walked through the graveyards that hold Kashmir’s dead, and have met with grieving families. I have listened to the testimony of a mother who sleepwalks to the grave of her son, attempting to resuscitate his body.

In June 2009, I travelled to Shopian to meet with the family of Asiya and Neelofar Jan, who were raped, reportedly by more than one perpetrator, then murdered. The complicity of Indian forces and state institutions pointed to obstruction of justice at the highest levels. The Shopian investigations, conducted by state institutions, shifted scrutiny from the paramilitary CRPF-recognized as an ‘Indian’ force-to the Kashmir police-understood as ‘locals’ (read: Muslims). The inquiry focused on manufacturing scapegoats to subdue public outcry-on ‘control’, rather than ‘justice’.

I have met with torture survivors-non-militants and former militants alike-who testified to the sadism of Indian forces. Over 60,000 people have been tortured in interrogation centres: people who have been water-boarded, mutilated, and paraded naked, who have had petrol injected into their anuses, who have been raped, starved, humiliated, and psychologically tortured.

In December 2009, the Tribunal released a report entitled Buried Evidence, which documents 2,700 hidden, unmarked, and mass graves, containing 2,943 bodies, mostly of men, across 55 villages in the Bandipora, Baramulla, and Kupwara districts of Kashmir. These bodies, bearing the marks of torture, burns, and desecration, were dragged through the night and buried next to homes, fields and schools. The graves were dug by locals on this village land at the behest of the military, paramilitary, and police.

…

The conditions of everyday life in Kashmir reveal the web of violence in which its civil society is confined. Through summer heat and winter snow, across interminable stretches of concertina wire, broken window-panes, barricades, check-posts, and literal and figurative walls, the dust settles, only to rise again. The agony of loss. The desecration of life. Kashmir’s spiritual fatalities are staggering. The dead are not forgotten; remembrance and mourning are habitual practices of dissent.

Angana P. Chatterji (@ChatterjiAngana) is Chair of the Political Conflict, Gender and People’s Rights Initiative, Centre for Race and Gender, University of California, Berkeley. Her recent publications include: BREAKING WORLDS: Religion, Law, and Nationalism in Majoritarian India; The Story of Assam; and Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India.