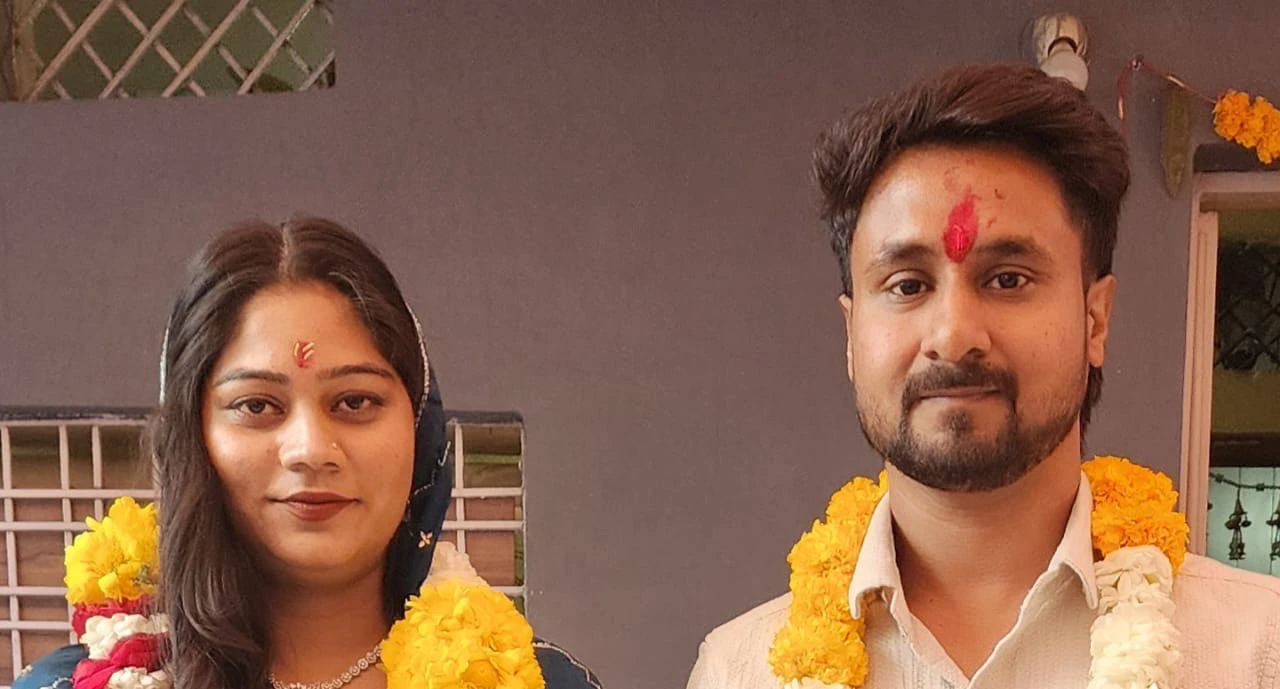

The Meghalaya honeymoon murder case unravels a profoundly unsettling intersection of premeditated violence, emotional disaffection, and the creeping normalization of betrayal within the institution of marriage.

The alleged role of Sonam Raghuvanshi does not reflect a spontaneous act of rage or emotional volatility, but rather a carefully choreographed execution reportedly plotted within just five days of her marriage.

That such a heinous act could be carried out with such chilling composure during a period traditionally associated with intimacy, trust, and new beginnings-during a honeymoon-has shocked not only the moral conscience but also the social imagination.

The use of hired contract killers, the strategic orchestration of logistics, and the selection of a remote location in the Northeast all point to what psychologists term instrumental aggression: an intentional, calculated infliction of harm aimed at dissolving an undesired marital bond and enabling a reunion with a previous romantic partner, Raj Kushwaha.

Tragically, this case does not stand alone. It is part of a growing and disturbing trend of post-marital conspiracies that expose deep ruptures in the emotional, psychological, and ethical fabric of our society. In Andhra Pradesh, T. Sahasra alias Ishwarya, along with her married lover, was arrested for plotting the murder of her husband merely weeks into their union.

In Rajasthan’s Kherli town in Alwar, Anita Raj allegedly watched in cold detachment as assassins she had paid ₹2 lakh strangled her husband. In yet another harrowing case from Uttar Pradesh, Dilip Yadav was gunned down just 15 days after his wedding-the crime allegedly masterminded by his wife Pragati and her lover Anurag. And the list goes on.

These narratives, cutting across region, class, and community, reveal not isolated instances of criminal intent but a broader social malaise. They speak to a dangerous collapse of emotional maturity, the corrosion of ethical boundaries, and the commodification of intimate relationships.

These are not merely legal aberrations; they are signs of a society struggling to navigate emotional conflict, personal autonomy, and moral clarity.

Psychologically, the conduct allegedly demonstrated by Sonam reflects deeply Machiavellian traits-systematic deceit, manipulation of ritual and familial expectations, and a stark exploitation of trust.

Her decision to select Nongriat, Cherrapunji (Sohra) in Meghalaya, a place geographically distant and perceived as legally opaque due to tribal protections, suggests not just logistical calculation but a dangerous assumption: that such remoteness might provide a shield from scrutiny. The entire plot reveals an unsettling precision, devoid of moral hesitation.

And yet, amidst this cruelty, the local community in Meghalaya responded with a quiet but profound dignity. Strangers in a distant land came together for a candlelight vigil to honour the memory of the victim, Raja Raghuvanshi. In a region far from his home, this collective act of mourning stood in sharp contrast to the calculated coldness that led to his death.

It became more than a tribute-it was a reaffirmation of empathy and shared humanity in a time when individual moral compasses appeared to falter.

In her searing work Stoned, Shamed, Depressed, Jyotsna Mohan Bhargava presents a compelling portrait of contemporary Indian youth. She notes: “There is a silent breakdown that’s eating away at an entire generation, masked by filters, buried under online validation, and fuelled by detachment from family and self.”

This invisible crisis, marked by alienation, emotional illiteracy, and a lack of sustained dialogue, creates an environment in which love, rejection, and failure are processed in isolation. The consequences, when not attended to, can be extreme.

Albert Bandura’s concept of moral disengagement offers a powerful lens here. When individuals cognitively separate their actions from ethical consequences, cruelty becomes possible without guilt.

Sonam’s alleged assertion that she was forced into marriage and thus would not bear responsibility for what followed is illustrative of such a disassociation.

The framing of oneself as a victim to justify violence is a psychological mechanism of denial-a severing of action from accountability.

This phenomenon also demands attention through the lens of feminist criminology. As Carol Smart has powerfully argued, criminal justice systems have historically neglected how patriarchal structures suppress women’s autonomy and emotional expression.

Philosopher Sandra Bartky’s concept of deformed desires-the distortion of needs and ambitions due to lifelong emotional repression-speaks directly to this issue.

When women are repeatedly denied agency, their emotional landscapes can become fractured, leading in some cases to extreme, distorted choices.

In this light, Sonam’s alleged actions reflect more than a crime; they reflect a condition. Her thwarted ambitions-whether to pursue an MBA or modernise her family’s business-may have been compounded by emotional suppression, familial pressure, and a lack of healthy coping mechanisms.

These are not just personal shortcomings; they are structural failures-failures in how society prepares individuals, especially women, to negotiate freedom, rejection, and emotional complexity.

The case thus sits at a volatile crossroads of law, psychology, gender, and cultural norms. It urges us to ask urgent questions: How do we equip young people to deal with emotional conflict? Where do they learn to process anger, disappointment, or broken relationships? What institutions are in place, if any, that can guide them toward resolution without violence?

Indian courts have long distinguished between crimes of passion and cold-blooded, premeditated murders, often reserving harsher sentences for the latter.

In K.M. Nanavati v. State of Maharashtra (1962), the Supreme Court convicted the accused under Section 302 IPC despite emotional provocation, due to the presence of deliberation. In Machhi Singh v. State of Punjab (1983), the apex court introduced the now-familiar “rarest of rare” doctrine, upholding the death penalty for a series of methodically executed revenge killings.

In Kehar Singh v. State (1988), the calculated assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was deemed to warrant the harshest punishment. Om Prakash v. State of Rajasthan (2002) reaffirmed that contract killings, often carried out without provocation and purely for gain, exemplify the gravest forms of moral and legal violation. In State of Rajasthan v. Kheraj Ram (2003), the Court once again underscored that deliberate and brutal murders must be penalised more strictly than impulsive acts.

The facts in the present case, such as the booking of one-way tickets, coordination with multiple actors, and selection of a location far from home, clearly reinforce the element of prior intent. But beyond legal reasoning lies the imperative to explore the deeper why-why would a young woman, ostensibly educated and ambitious, arrive at such a moral collapse?

A disturbing parallel lies in the 2018 Telangana honour killing of Pranay, orchestrated by his wife’s father to uphold caste pride. In both cases, it was rigid social control, emotional repression, and entitlement-not just individual hatred-that fuelled the violence.

Literary works offer resonant insights. Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen’s iconic protagonist, is a woman trapped in a stifling marriage who responds not with rebellion but with destruction-of herself and others.

Miss Julie, the titular character in August Strindberg’s play, spirals into tragedy when her desires clash fatally with patriarchal and class-based expectations. The Meghalaya case, too, is a narrative of emotional suffocation and the weaponisation of personal despair.

As senior advocate of Delhi High Court, Saurabh Kirpal observes in his book Sex and the Supreme Court, dignity and autonomy must empower the individual to choose or reject a partner. But in practice, this ideal remains aspirational, as marriages in India continue to be tightly mediated by caste, class, and community. Legal recognition of individual rights is often at odds with social reality.

Nivedita Menon, in Seeing Like a Feminist, notes with clarity: “If you bring Fundamental Rights into a family… that family will collapse.” This is because the family as it exists is premised on hierarchies of gender and age, where rights are negotiated rather than guaranteed.

And so we return to a deeper truth, one that often escapes institutional conversations: empathy must be cultivated. It does not come on its own. It is not an automatic reflex but a deliberate skill, nurtured through education, modelled in homes, and reinforced through media, community, and law.

Martha Nussbaum reminds us in Upheavals of Thought that emotions like empathy and compassion are not spontaneous; they are socially taught.

Roman Krznaric writes in Empathy: Why It Matters and How to Get It, “Empathy is not a fixed trait. It can be learned and cultivated over time.” Without this cultivation, people-particularly the young-are left to navigate love, rejection, ambition, and pressure with little more than instinct and impulse.

The Meghalaya honeymoon murder serves as a grim wake-up call. It reminds us that when emotional literacy is denied, when social expectations silence personal choice, and when mental health is pushed to the margins, law alone cannot carry the burden of justice.

We must create spaces where empathy is not the exception, but the norm. Only then can we begin to stem the tide of such tragedies-not with fear or retribution, but with a commitment to emotional resilience and collective care.