There was a time when Muslim leaders in Uttar Pradesh were not just bystanders in its political theatre. They were an important part of the discourse, shaping coalitions, influencing agendas, and giving voice to nearly a fifth of the state’s population.

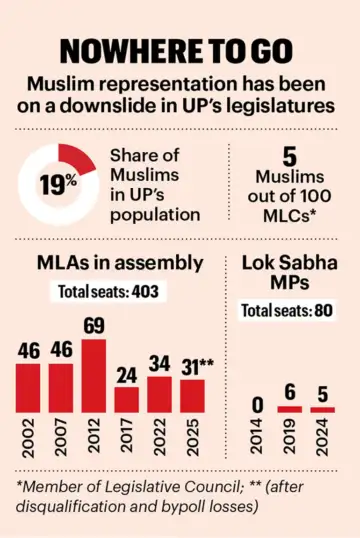

No longer so. The spotlight has shifted, the applause has faded. And what remains is a ringing silence. Muslim political representation in UP has entered its most diminished phase in decades. In a state where the community makes up more than 19 per cent of the population, its representation in the current assembly is just 31 seats, or 7.7 per cent of the 403-member House (see Nowhere to Go).

This is a far cry from 2012, when 69 Muslim candidates were elected, marking the highest-ever representation since Independence. The lowest was 17 in 1991, before improving to 24 a year after the Babri Masjid demolition, 31 in 1996, 46 in 2002 and 2007, before plummeting to 24 in 2017. After a modest uptick in 2022 to 34 (with the Samajwadi Party accounting for 31 of these wins, and the Rashtriya Lok Dal or RLD, and Suheldev Bharatiya Samaj Party or SBSP, both then SP allies, contributing one and two MLAs respectively), it has dropped again following the disqualification of Mau MLA Abbas Ansari, and bypoll losses in Rampur and Kundarki.

But the decline in representation is not just about numbers, it reflects a deeper realignment in UP’s politics. The political centre of gravity has shifted, and under Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, the BJP has maintained its dominance without fielding a single Muslim candidate in successive elections, consolidating majoritarian support while pushing earlier models of minority-based identity politics to the margins.

The situation remains as dismal in the 100-member state Legislative Council-where they remain squeezed to five (two BJP and three SP). The void is also stark in the Lok Sabha. Only five of UP’s 80 MPs are Muslim, all from the Opposition (four SP and one Congress). Imran Masood, the Congress MP from Saharanpur, is reconciled to the current political situation, but says, “People talk about the winnability of Muslim candidates, but a discussion about it can start only when you give them tickets.”

The situation remains as dismal in the 100-member state Legislative Council-where they remain squeezed to five (two BJP and three SP). The void is also stark in the Lok Sabha. Only five of UP’s 80 MPs are Muslim, all from the Opposition (four SP and one Congress). Imran Masood, the Congress MP from Saharanpur, is reconciled to the current political situation, but says, “People talk about the winnability of Muslim candidates, but a discussion about it can start only when you give them tickets.”

Over the past decade, all three major parties in UP apart from the BJP-Samajwadi Party (SP), Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Congress-have scaled back Muslim representation for electoral reasons. The SP, once defined by its Muslim-Yadav coalition, has gradually shifted focus to its new PDA (Pichhda, Dalit, Alpasankhyak) formula. In recent years, as the political narrative has further consolidated around Hindu identity politics and with the BSP’s grip on Dalit voters weakening, the SP has actively courted Dalit support while being careful not to alienate Hindu voters. Mayawati’s BSP, too, has turned away its focus from Muslim candidates and pivoted instead to reinforce its traditional base among Dalits and backward classes, especially after the 2024 Lok Sabha election. Across the board, what emerges is a retreat from minority-centric ticket distribution toward strategies centred on majoritarian and caste-based electoral calculations.

A LEADERSHIP VACUUM

There are those who attribute the decline in Muslim political representation in UP to the collapse of a specific section of the leadership that thrived on a criminal-political nexus. Leaders like Azam Khan, Mukhtar Ansari and Atiq Ahmed once embodied a brand of assertive Muslim leadership in UP politics. They were controversial, yet undeniably influential. The issue before the community now is that their decline has created a vacuum rather than paving the way for a new generation of leaders. Khan is entangled in dozens of legal cases, Ansari died in jail and Ahmed was shot dead while in police custody. Others, including MLAs like Kairana’s Nahid Hasan and Kanpur Nagar’s Irfan Solanki (now disqualified), are also caught up in prolonged legal battles.

Since the BJP’s rise to power in 2017, the narrative in UP’s political landscape has shifted from a spectrum of identity-driven themes to governance- and Hindutva-oriented ones. Muslim leaders, traditionally aligned with the SP and BSP, have struggled to find space in this new order. The Yogi government’s hardline stand against crime has provided conducive legal grounds to act against many of these figures. While the Opposition describes this as a selective crackdown aimed at silencing Muslim voices, the state maintains that it is simply enforcing the law.

But then criminality in UP politics is a widespread phenomenon. According to the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), in the 2022 UP assembly election, 205 of the 403 MLAs (over 51 per cent) contesting had declared criminal cases against themselves. Of these, 111 were from the BJP and 71 from the SP. The numbers remained high even for serious criminal charges-90 BJP and 48 SP legislators had declared such cases. Responding to allegations that the BJP is targeting Muslim politicians, Om Prakash Rajbhar, the UP cabinet minister for minority welfare, NDA ally and SBSP chief, claimed, “Many non-Muslim leaders are also facing legal action, which the Opposition conveniently overlooks.” Under the Yogi government, legal action is taken “as per the law and without bias”, he insists.

But then criminality in UP politics is a widespread phenomenon. According to the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), in the 2022 UP assembly election, 205 of the 403 MLAs (over 51 per cent) contesting had declared criminal cases against themselves. Of these, 111 were from the BJP and 71 from the SP. The numbers remained high even for serious criminal charges-90 BJP and 48 SP legislators had declared such cases. Responding to allegations that the BJP is targeting Muslim politicians, Om Prakash Rajbhar, the UP cabinet minister for minority welfare, NDA ally and SBSP chief, claimed, “Many non-Muslim leaders are also facing legal action, which the Opposition conveniently overlooks.” Under the Yogi government, legal action is taken “as per the law and without bias”, he insists.

That said, there is no denying that the alleged “criminal-political overlap” has left many Muslim leaders vulnerable. Once stripped of political protection, their legal troubles escalated rapidly. The BJP’s sustained dominance has deepened this marginalisation, with Muslim figures unable to mount a credible counter. Indeed, for parties like the SP or BSP, it is now difficult to even promote Muslim leaders without risking a backlash.

WHEELS WITHIN WHEELS

But there are other factors at play as well. Hilal Ahmed, political scientist and professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), feels that the reasons for Muslim representation declining in UP are more due to changing political strategies than overt exclusion. He goes back to the emphasis on the winnability factor. “At present, the political discourse is dominated by Hindutva, no political party can ignore that. Because of this, the term ‘Muslim’ has acquired a negative connotation. Even leaders like (SP chief) Akhilesh Yadav have shifted from using the term ‘Muslim’ to ‘minorities’,” he points out.

Hilal also believes that political narratives heavily influence leaders as well as the electorate. “Earlier, from around 1992 to 2010, secularism was the dominant narrative inIndian politics. Every political party wanted to be called secular, even the BJP, which described others as ‘pseudo-secularists’ while still embracing the label for itself,” he notes. “Today, the environment is very divisive. If that does not change, it will become difficult to imagine any form of non-identitarian politics.”

But then, winning elections is just one part of democracy, asserting India’s pluralistic values is another. “We do need Muslim MPs and MLAs to make our institutions inclusive and diverse. But we should not ask political parties to give tickets to Muslims, or expect that Muslims will vote only for Muslim candidates. Instead, we should expect parties to recognise Muslim presence in the legislative chambers,” says the CSDS professor. Hilal also flagged the growing lack of internal inclusiveness within the political parties themselves, warning that if such trends continue, the very meaning of democracy risks being reduced to just contesting and winning elections.

But then, winning elections is just one part of democracy, asserting India’s pluralistic values is another. “We do need Muslim MPs and MLAs to make our institutions inclusive and diverse. But we should not ask political parties to give tickets to Muslims, or expect that Muslims will vote only for Muslim candidates. Instead, we should expect parties to recognise Muslim presence in the legislative chambers,” says the CSDS professor. Hilal also flagged the growing lack of internal inclusiveness within the political parties themselves, warning that if such trends continue, the very meaning of democracy risks being reduced to just contesting and winning elections.

Even within the Opposition ranks, the signs of discomfort are visible. The SP’s decision to name Azam Khan a star campaigner in the 2024 Lok Sabha election despite his imprisonment drew internal criticism and highlighted a growing unease over the party’s traditional formula of minority consolidation. The absence of a strong, unifying leadership has also left the vote fragmented, which is again cited as a reason for multiple Muslim candidates sprouting in community stronghold seats. Newer outfits like Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM (All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen) and Chandra Shekhar Azad’s Azad Samaj Party have tried to fill the vacuum, but have yet to gain meaningful ground.

The results of the assembly bypolls in November 2024, where the SP lost in Muslim strongholds such as Kundarki, Meerapur and Rampur, show that revival is a long way off. Kundarki, in particular, exemplified this crisis. The constituency has over 60 per cent Muslims, the local MP is from the community (Zia Ur Rehman Barq from Sambhal), and the BJP had not won here in over 30 years. But this time the BJP did, with party candidate Ramveer Singh taking an unprecedented 76 per cent of the vote. The Opposition had its share of excuses-the 10 dummy Muslim candidates (other than the SP nominee), security officials allegedly not allowing Muslim voters to come out and vote in certain areas-but couldn’t evade the elephant in the room, the fact that a sizeable section of the community had voted for the saffron party. This also segues into Prof. Hilal’s argument that “it’s a false assumption that Muslims will automatically vote for Muslim candidates.”

One must laud the community’s efforts at staying ahead of the polarisation debate in UP, but the collapse of the old Muslim leadership model elicits broader questions, not just about minority representation but about the kind of leadership that is required to take its place.