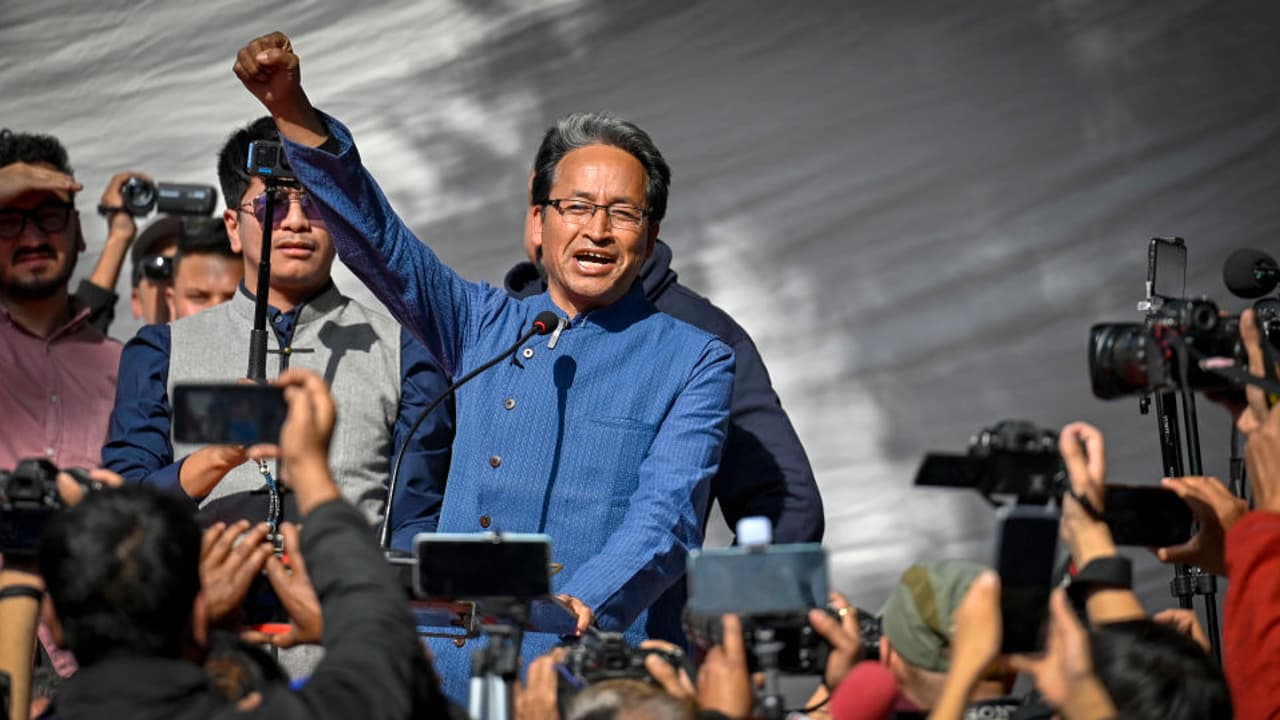

Once a government ally, Sonam Wangchuk now leads protests demanding statehood and constitutional safeguards for Ladakh. Following Ladakh protests that turned violent, he was arrested under the National Security Act amid controversy.

Bengaluru: Most people would know Sonam Wangchuk as Phunsukh Wangdu, the brilliant innovator portrayed by Aamir Khan in the 2009 blockbuster film 3 Idiots. However, the real Sonam Wangchuk’s contributions to education, environmental sustainability, and community development extend far beyond his cinematic representation, making him one of India’s most impactful social innovators. While he is under scrutiny now for his active role in leading protests demanding greater autonomy and constitutional safeguards for Ladakh, Sonam Wangchuk was once the government’s trusted advisor on several programmes. He had even celebrated the abrogation of Article 370, seeing it as an opportunity for Ladakh to gain greater administrative focus and developmental support. However, he became a vocal critic of New Delhi’s policies in Ladakh is rooted in his evolving concerns over regional autonomy, cultural preservation, and environmental sustainability.

Sonam Wangchuk’s Early Years

Born on September 1, 1966, near Alchi in Ladakh’s Leh district, Wangchuk’s childhood was markedly different from conventional educational experiences. Until age nine, he received no formal schooling, learning instead from his mother in his native language. This early foundation would later shape his revolutionary approach to education reform. When his father, Sonam Wangyal, became a minister in the Jammu and Kashmir Government in 1975, young Wangchuk was sent to Srinagar for schooling. The experience proved traumatic as he faced discrimination for his appearance and struggled with an unfamiliar language. This alienation drove him to flee to Delhi in 1977, where he successfully appealed to a Kendriya Vidyalaya principal for admission. These formative struggles with an education system disconnected from his cultural reality became the catalyst for his life’s work. Wangchuk went on to earn his B.Tech in Mechanical Engineering from the National Institute of Technology Srinagar in 1987, financing his own education due to disagreements with his father. Years later, in 2011, he pursued advanced studies in Earthen Architecture at Craterre School of Architecture in Grenoble, France.

The Start of a Revolution

In 1988, fresh out of engineering college, Wangchuk joined forces with his brother and five colleagues to establish the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL). The organization emerged from a collective frustration with an educational framework that felt imposed and irrelevant to Ladakhi students. The movement’s cornerstone initiative, Operation New Hope, launched in 1994, represented a groundbreaking approach to educational reform. This three-way partnership between government authorities, village communities, and civil society organizations fundamentally restructured how education functioned in Ladakh. The program empowered villages to create education committees that took ownership of government schools, retrained teachers in student-friendly pedagogical methods, and developed localized textbooks reflecting Ladakhi culture and environment.

Special School for Failed Students

For students who continued to struggle despite systemic reforms, Wangchuk created something unprecedented—the SECMOL Alternative School Campus near Leh. This institution operates on a radical principle: admission is reserved for students who have failed their state examinations, not those with high grades. At this unique campus, Wangchuk applies his engineering expertise to teach innovation through hands-on projects. The school’s buildings themselves serve as teaching tools as it was constructed from earth and mud. Using passive solar architecture principles, these structures maintain comfortable temperatures of 15°C indoors even when winter temperatures outside plummet to -15°C. The entire campus runs on solar energy, requiring no fossil fuels for cooking, lighting, or heating.

Ice Stupa to Solve Water Crisis

Perhaps Wangchuk’s most celebrated innovation addresses one of Ladakh’s most pressing challenges of water scarcity during critical planting months. In late 2013, he invented the Ice Stupa, an artificial glacier that revolutionizes water storage in mountain regions. The concept is elegant yet powerful: during winter, when stream water flows abundantly but remains unused, the Ice Stupa technique freezes this water into massive cone-shaped ice formations resembling Buddhist stupas. These artificial glaciers can store thousands of liters of water. As spring arrives and farmers desperately need water for planting, the stupas begin melting, providing irrigation precisely when natural glacial melt hasn’t yet begun. By February 2014, Wangchuk’s team had built a two-story prototype storing approximately 150,000 liters of water. The innovation gained international recognition, with authorities in the Swiss Alps inviting him to construct Ice Stupas in Pontresina, Switzerland, in 2016, both for water management and winter tourism attractions. Beyond agriculture, Wangchuk has adapted the Ice Stupa technique for disaster mitigation. In 2016, the Sikkim government invited him to address the dangerous South Lhonak Lake using his siphoning technique. His team camped for two weeks at the high-altitude lake, installing drainage systems to reduce flood risks.

Key Role in Media and Governance

From 1993 to 2005, he founded and edited Ladags Melong, Ladakh’s only print magazine, providing a crucial platform for regional voices. He has served on numerous governmental bodies, including the National Governing Council for Elementary Education in the Ministry of Human Resource Development (2005), the Jammu and Kashmir State Board of School Education (2013), and advisory positions with the Ladakh Hill Council Government. In 2016, he initiated FarmStays Ladakh, enabling tourists to experience authentic Ladakhi life by staying with local families, with the project managed by mothers and middle-aged women, providing them economic independence. In February 2021, responding to the needs of Indian soldiers serving in extreme high-altitude conditions, Wangchuk developed solar-powered mobile tents. Each tent accommodates approximately ten soldiers and captures solar heat during the day to maintain warmth through freezing nights.

Building on decades of success with experiential learning, Wangchuk founded the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives Ladakh (HIAL) alongside Gitanjali J Angmo. This institution represents his vision for higher education—moving beyond theoretical classroom learning to equip young people with practical skills relevant to their unique geographical and cultural context. HIAL aims to make university education meaningful for mountain communities, addressing what Wangchuk sees as a critical problem: universities, especially those in mountainous regions, have become disconnected from the realities of daily life.

According to reports, Wangchuk was the government’s preferred expert for various initiatives in Ladakh, from water conservation and clean energy to tourism and pashmina development. He headlined flagship government events including Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav celebrations and World Heritage Week. In 2022, BJP national general secretary Vinod Tawde publicly thanked Wangchuk for “working together towards betterment of our Nation, specially welfare of our students.” Wangchuk had also served on the Maharashtra International Education Board since 2018. In December 2019, then Union Tribal Affairs Minister Arjun Munda acknowledged Wangchuk’s advocacy for Scheduled Area status for Ladakh. Successive Lieutenant Governors of Ladakh, RK Mathur and Brig (Dr) BD Mishra, have arranged meetings with him to discuss development initiatives.

The Rise Of a Dissenter

Wangchuk began taking a more radical route in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370, which allegedly stripped the region of its autonomy under Article 370. While he initially welcomed the change, anticipating greater development opportunities, he soon became concerned about threats to local land rights, cultural heritage, and environmental preservation. This shift prompted him to push for constitutional protections, including bringing Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule. In January 2023, he attempted a climate fast at Khardung La pass to highlight environmental challenges, though authorities prevented the protest citing dangerously low temperatures. In March 2024, he undertook a 21-day hunger strike demanding statehood and constitutional safeguards for Ladakh. Most dramatically, in September 2024, Wangchuk led a march on foot from Ladakh to Delhi. Upon reaching the capital, he and his supporters were detained by Delhi Police at the Singhu border before being released on October 2, 2024.

In between this change, he was also emerging as the voice of Ladakh. Following India-China border clashes at Galwan in 2020, he appealed to Indians to exercise their “wallet power” by boycotting Chinese products that gained massive popularity. The trouble that was brewing finally erupted on September 26, after Wangchuk was arrested under the National Security Act following deadly protests. He was accused of inciting mob violence and shifted to Jodhpur Jail.

The bone of contention is Wangchuk’s participation at the Breathe Pakistan climate event in Islamabad. He was one of several international experts at the Dawn group-organized event, alongside World Bank and UN representatives. Reports suggest that a Pakistani intelligence agent was arrested for allegedly circulating footage of Wangchuk’s protests across the border. This led Ladakh authorities to probe potential foreign connections, pointing to Wangchuk’s involvement in international forums and his NGO’s receipt of foreign funding. Wangchuk’s wife Gitanjali Angmo strongly denied any allegations of foreign or anti-national links, calling them baseless and politically motivated. She emphasized that his work has always followed principles of nonviolence and environmental advocacy, aimed at protecting Ladakh’s culture, ecology, and local communities rather than serving any external interests.