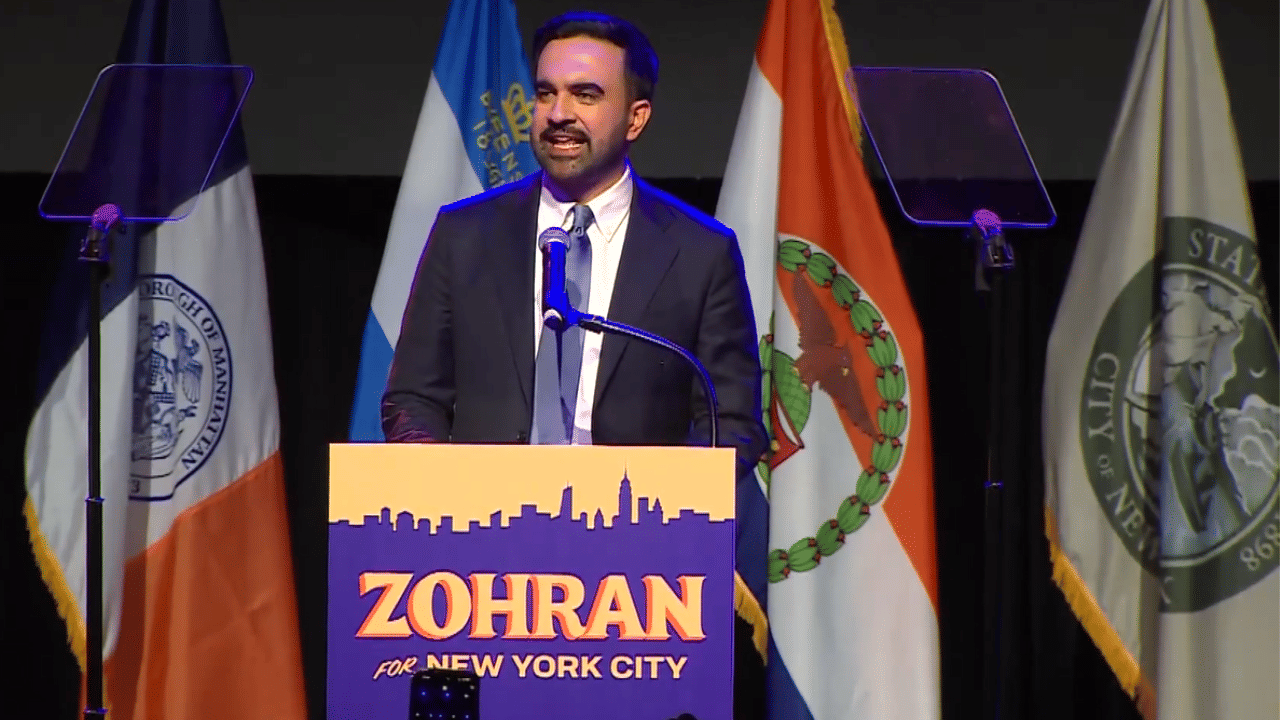

Zohran Mamdani’s victory as the Mayor of New York City isn’t just a stunning political feat; it’s how revolutions look in a democracy. When desperate voters allow themselves to be lulled into deceptive hope of a utopian democracy, where magically everyone gets taken care of economically equally well by the state.

But such revolutions are doomed for failure. Why? Because they are fuelled by populist Kool-Aid and not the hard realities of an economic system where the concept of labour and reward is rapidly changing. Because they put too much store in the political system and too little responsibility on its constituent parts—the people themselves. It’s like a student expecting their teacher to give them an A without putting in the required effort.

Unfortunately, what we are witnessing is just the start of such revolutions. Yet, when the capital of capitalism decides to put its future in the hands of an avowed socialist, you know that there’s a problem with both capitalism and democracy.

Capitalism of the Few

Ever since the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s, the world has continued to get richer. In 1820, an estimated 90% of the world population lived in extreme poverty. Today, that number is reported to be just 10%. As productivity improved and demand for labour shot up, the resulting economic wealth made everyone more affluent. Buoyant taxes allowed governments to spend more on infrastructure and welfare, and the globalisation of the 1990s accelerated the geographic distribution of economic wealth.

The world has never been this rich, but neither has inequality in the modern world been this wide. According to the World Inequality Database, the richest 1% globally own about 27% of all wealth across 210 economies. In India, the wealth of the richest 1% grew by 62% between 2000 and 2023, and they currently hold 40% of the country’s total wealth—the highest since 1961.

In China, the top 1% own a third of the nation’s wealth, and their wealth grew by 54% between 2000 and 2023—slower than it did in India. In the US, the top 1% own almost 43% of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 50% of American households hold less than 5%.

As a result, the average citizenry is feeling impoverished and left out. In New York City (or the Bay Area), it is easy to feel poor even if you are making $100,000 a year. But guess what the median income is in the Big Apple? $79,713, as per the US Census Bureau. In some boroughs, such as the Bronx, it is significantly lower at $47,036.

It’s no surprise, then, that Mamdani’s promise of a rent freeze for rent-stabilised apartments, subsidised groceries, free bus rides, and childcare assistance struck a deep chord with the young and the poor. His vote share in the Black neighbourhoods was 61%; 57% in Hispanic, and 47% in Asian. In precincts with voters aged 45 or below, his lead was 30% over the nearest competitor.

Democracy Under Stress

In a world where disproportionate economic rewards are reserved for those who are masters of AI and other high technology, it is a given that those without such coveted skills are doomed to scrape the bottom of the barrel.

A comprehensive study by the World Inequality Lab projects that “in a business-as-usual scenario, overall global income inequality will remain largely unchanged in 2050 compared to today”. The world’s richest 1% will continue to pocket 17% of worldwide income, while the share of the world’s poorest 50% will only marginally rise from 10% to 12%. I believe the situation could get worse than what the World Inequality Lab is projecting. When 23% of the graduating class at Harvard Business School does not receive any job offer, or it takes 3 months for Carnegie Mellon computer science graduates to land a job–you know that it’s not business as usual.

What does this mean for democracy? With power to elect governments squarely in their hands, people buffeted by economic uncertainty, stagnant or falling incomes, but rising aspirations, will want to elect those politicians who promise them relative immunity from such problems. Enter promises of affordable housing, subsidised groceries, free public transport, etc.

But a democracy based on a sense of economic entitlement—where the responsibility of individual well-being is outsourced to the elected politicians–is doomed for failure sooner than later. Just like Mamdani cannot enrich the average New Yorker by penalising (and driving away) the city’s super-rich, no government can afford to feed and house an ever-growing number of entitled voters. Someone has to pay the bills. The government may own the currency printing press, but it cannot print unlimited currency notes to make everyone rich. If you do, then you end up like what Venezuela experienced in 2019—hyperinflation of, wait, 10 million per cent!

Instead of post-tax redistribution policies—essentially handouts—what works better is pre-tax redistribution, i.e. greater public spending on education, skilling, healthcare, and a reasonable minimum wage. But making such an investment needs political discipline and medium-term pain for the masses. The incentive for politicians to think beyond their elected term of four or five years is little. They’d rather make promises they know they can’t keep than tell the truth to voters. It’s a vicious cycle that repeats every election. That, then, dear reader, is the problem with democracy—and the reason why China’s centralised and permanent political leadership, but decentralised, capitalist economy seems to work better!