Since China’s first atomic test in 1964, its nuclear arsenal has evolved from deterrence to coercion, enabling Beijing’s expansionism from the Himalayas to the South China Sea under a shadow of strategic arrogance.

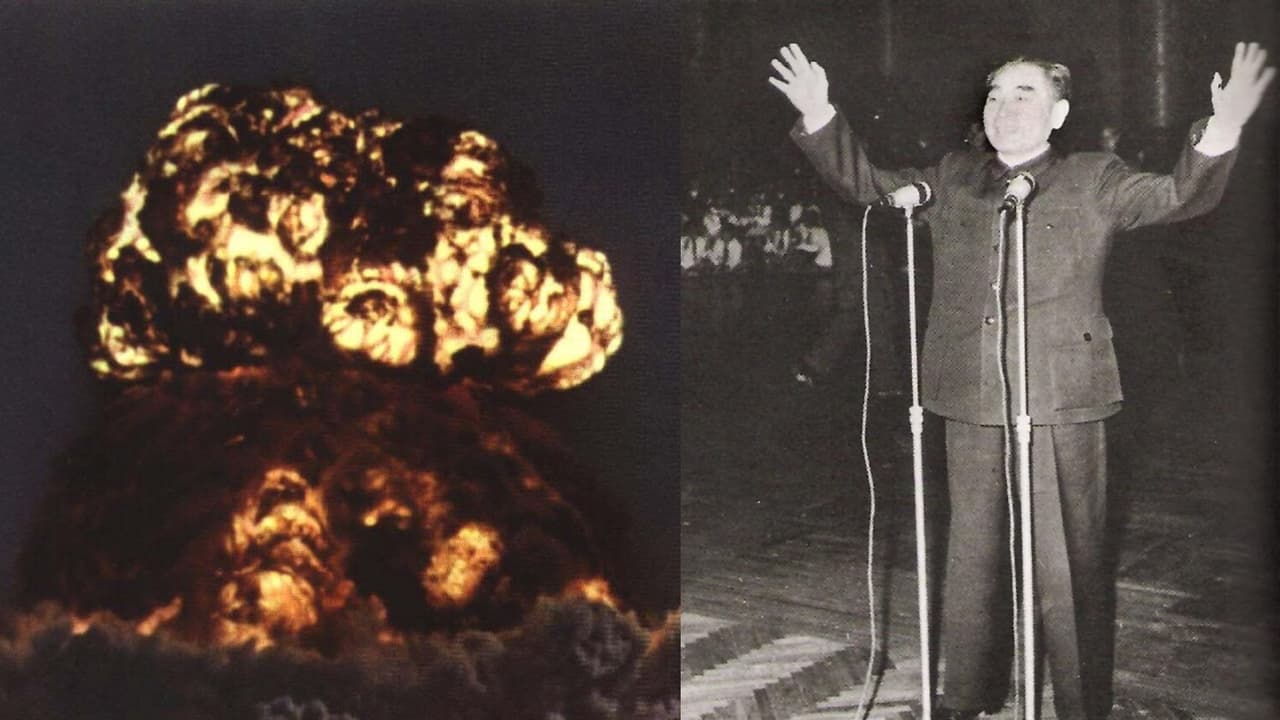

New Delhi: On October 16, 1964, at Lop Nur, China detonated its first atomic bomb under Project 596, climbing into the elite nuclear club. From that moment, Chinese foreign policy gained a new vocabulary – one forged not from caution but from coercion. What began as a defensive pursuit of sovereignty soon mutated into strategic arrogance, with nuclear capability emboldening Beijing to brandish force along its peripheries. The tests did not just deter threats – they bred an illusion of invulnerability that now underpins Chinese expansionism from the Himalayas to the South China Sea.

From Deterrence to Dominance

Between 1964 and 1967, China’s nuclear programme accelerated at a startling pace. Within a year of its first test, Beijing delivered a functional airborne nuclear bomb; within three, it had operational missile warheads and a thermonuclear design ready for deployment.

The rapid march from fission to fusion was driven by Mao Zedong’s conviction that true sovereignty demanded fear-based respect. Nuclear capability became China’s ultimate insurance against encirclement – first by the United States, then by an increasingly hostile Soviet Union.

Yet Mao’s brand of deterrence was not one of restraint. It was an assertion that the People’s Republic could act with impunity in its neighbourhood, immune from conventional retaliation.

The 1969 Lesson: Arrogance Meets Realpolitik

This hubris found its test at the Ussuri River in 1969, when Chinese and Soviet forces clashed in the histrionic Sino-Soviet border conflict. By then, Beijing possessed a rudimentary but deployable nuclear capability.

The Soviet Union’s nuclear superiority, however, turned Mao’s deterrence calculus inside out. Newly declassified assessments reveal that by October 1969, Mao had fled Beijing, fearing a Soviet nuclear strike, prompting China to ready its small arsenal for last-resort retaliation. Ironically, what began as nuclear bravado ended in paranoia.

Yet the psychological imprint remained. The experience convinced Chinese leaders that nuclear capability could shield coercive risk-taking, provided the adversary’s will could be questioned. It was this lesson – wrapped in insecurity but expressed through arrogance – that would later inform China’s behaviour across Asia.

Nuclear Conceit in Maritime and Himalayan Frontiers

China’s subsequent postures across contested regions reflect this mindset. In the South China Sea, Beijing’s sweeping territorial claims – anchored by militarised artificial islands and forward-deployed missiles – echo the same coercive confidence that first emerged after 1964.

A 2025 Chatham House study warns that within a decade, Beijing could effectively dominate the maritime space through nuclear-backed deterrence of Western intervention. Against neighbours like Vietnam and the Philippines, China’s conventional provocations rely on the implicit nuclear shadow: a reminder that escalation thresholds favour Beijing.

The same strategic arrogance is visible in the Himalayas. Since the mid-2000s, China’s modernization of dual-capable missile systems and precision-strike assets has allowed calibrated aggression along the Line of Actual Control without fear of proportionate retaliation.

Beijing’s repeated transgressions into Indian territory, from Doklam to Galwan, can be read as acts of deterrence by denial – driven by the belief that India, lacking comparable nuclear coercion capability, will hesitate to escalate.

The Modern PLARF: Precision and Posturing

Today, this arrogance finds expression in the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF).

Under Xi Jinping’s direction, the PLARF has transformed into a versatile instrument capable of dual nuclear-conventional deterrence.

Extensive 2025 exercises showcased realistic multi-domain simulation – from high-altitude launches to degraded command link recoveries – demonstrating China’s readiness to sustain operations under nuclear conditions.

Xi’s political rhetoric has fused nuclear expansion with national rejuvenation, positioning the arsenal as both shield and sword.

A recent U.S. Army assessment calls this a “deliberate bid to elevate coercive military measures into an enduring competition between systems”.

This nuclear resurgence departs dramatically from China’s earlier “minimum deterrence” pledge. By seeking parity with American and Russian arsenals, China is dismantling the very restraint that insulated Asia from Cold War-style nuclear brinkmanship. The result is a spiral wherein nuclear arrogance serves as both instrument and justification for assertive behaviour—whether it be over Taiwan, the Indian border, or the South China Sea.

The Arrogance Imperative

Beijing cloaks its nuclear expansion in the language of deterrence – claiming it seeks stability through credible defence. In truth, its trajectory mirrors that of a power convinced that impunity ensures influence.

The 1964 test planted the idea that nuclear capability is not merely a shield, but a sledgehammer – one that bends geography and diplomacy to its will. Each border standoff and maritime provocation since has reinforced this conviction.

The world now confronts a nuclear-armed China that equates restraint with weakness and conflates deterrence with dominance.

Its arsenal no longer deters war; it enables coercion. This is not deterrence – it is nuclear arrogance, and it fuels the expansionism that destabilises Asia’s fragile balance.