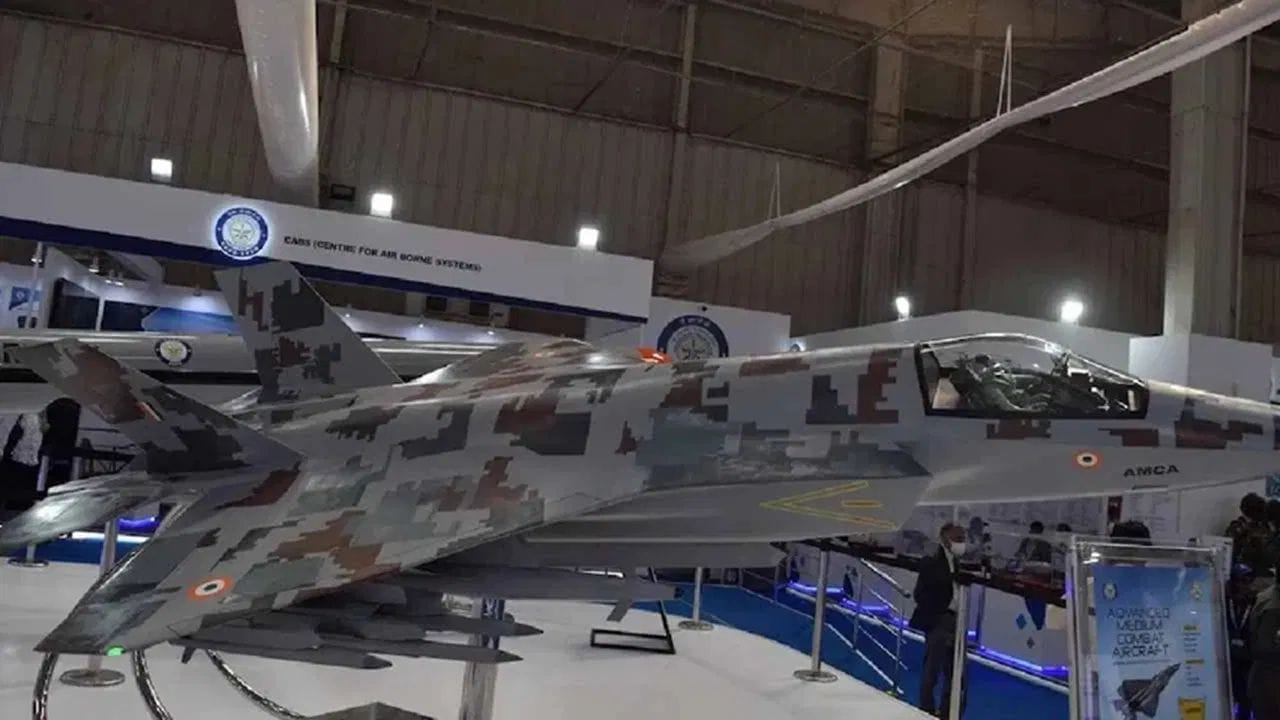

Contract can be given to private sector to make 5th Stealth Fighter Jet.

Reports last week indicated that the private sector may be given priority to manufacture the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), a fifth-generation multirole stealth aircraft being developed for the Indian Air Force and Navy. If this happens, it would be a departure from the government’s normal defense procurement strategy under which it uses Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) to manufacture such aircraft, including the light combat aircraft Tejas.

Although HAL shareholders have made their opinion clear in the past few days—its share price has fallen nearly 14 percent since the beginning of the month—but involving the private sector in this complex and expensive endeavor is a step in the right direction. But some conditions are also included in it.

challenging change

The Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) under the Department of Defense Research and Development is leading the development of AMCA. In cases like Tejas, HAL, being a government company, was naturally selected as the main partner for integration and manufacturing. But now there is a possibility of change in this. Retired Air Vice Marshal Manmohan Bahadur believes that it would be good to involve private companies and create another option, as HAL has a large number of orders for the Tejas aircraft.

However, this change will be challenging for Indian private companies. Names of companies like Tata Advanced Systems, L&T and Bharat Forge figure in the list of potential companies for integration and manufacturing of the fifth generation aircraft, but their level of expertise in such projects varies.

Some companies are part of the global supply chain of companies like Airbus and Boeing, some use their high-precision manufacturing capabilities to manufacture artillery, while some are working on rocket manufacturing in collaboration with India’s space agency Iero. Being the main integrator and maker of a fifth generation fighter aircraft, which requires complexities and additional security systems, is a fundamentally different kind of challenge.

But it is not that the private sector has to start from scratch. Defense analyst Angad Singh tells ET’s report that these companies have been manufacturing aircraft parts and even complete parts as suppliers for the global market.

The main challenge is to expand their scope of work. It is a difficult and risky job that involves much more than high precision manufacturing. In this area, the company that wins the AMCA agreement will be responsible for the overall structure, system integration, interaction of software with sensors and the lifecycle of the aircraft. It is clear that private sector companies will need some guidance.

mass recruitment

Although some of these recruitments will be done by the ADA and the Defense Ministry, a lot will depend on who is recruited. Former Defense Secretary G Mohan Kumar says in media reports that the biggest challenge for any private company getting a contract is mobilizing resources and manpower: it is a question of creating a complete ecosystem that can make the parts. We already have a similar ecosystem for Tejas.

This means that if everything goes according to plan, it will signal the start of large-scale recruitment by the manufacturing company that wins the AMCA contract. Singh says that whichever company wins the contract, it will recruit a large number of people from the existing ecosystem. Why wouldn’t they do that? The truth is that institutional experience can be bought. It’s not really an option. Kumar says that the private sector can bring innovation because they can bring the best people.

There is expected to be a huge surge in demand from retired employees of HAL and ADA as well as all those working in the aerospace sector at the global level. As Singh explains that they are not bound by government pay scales and recruitment rules. Anyone will easily come to you if you can give them a check for a big amount. Singh also warns the private sector against placing unrealistically low bids. Often people make overly ambitious bids. No one can stop you from bidding very low. But when this happens, there is every possibility of the program getting derailed. We have seen this in other areas also. It is very important to make realistic bids.

What will be the future of HAL?

There is an expectation in the entire ecosystem that the private sector will demonstrate its efficiency through this contract. Part of this expectation stems from the need to show returns. Whatever the governance of the contract, Singh says, the private sector will have to bear financial costs that HAL does not have to bear.

HAL has huge cash reserves and no opportunity cost as it is not an innovation-based creative company. For example, Tata cannot invest Rs 5,000 crore and expect good returns because they could have invested it elsewhere. As Singh said, the private sector by its nature believes in working faster, because it is based on capital efficiency, which government companies do not have to struggle with.

So what is the position of HAL in this situation? Anticipating that its shares would be affected due to speculations that it was being kept out of the AMCA agreement, the company had to issue a statement saying that it had not received any official information in this regard.

Although the Bengaluru-based company has faced the ire of the Indian armed forces over the years due to delayed deliveries of aircraft, it still remains a significant player in the ecosystem, with orders for hundreds of aircraft, as well as maintenance contracts from the armed forces. This pipeline is enough to support its balance sheet for more than a decade.

But it has to learn some lessons, an important one being sharpening its approach. Kumar believes that one reason for HAL not getting such contracts automatically is that HAL takes decisions very slowly. Nor do they take the kind of risks that the private sector can. In the long term, HAL should focus its energy on solving that problem.