Your journey from television to cinema has been quite long and far-reaching?

Yes, I agree with you. After I did Chanakya on Doordarshan, I spent about many years studying the erotic sculpture of Khajuraho from Vedic times to modern times.

I studied sexual mores in this country and started a film on the subject, which almost got made, then shelved after 95 per cent was complete. The film starred me, Om Puri, Paresh Rawal, Kitu Gidwani, etc. It entailed huge losses. I later made another period soap, Mrityunjay. I had won several awards for Mrityunjay. I remember Javed Akhtar saying our middle class has become third class. It doesn’t react favourably to progressive ideas in art or life.

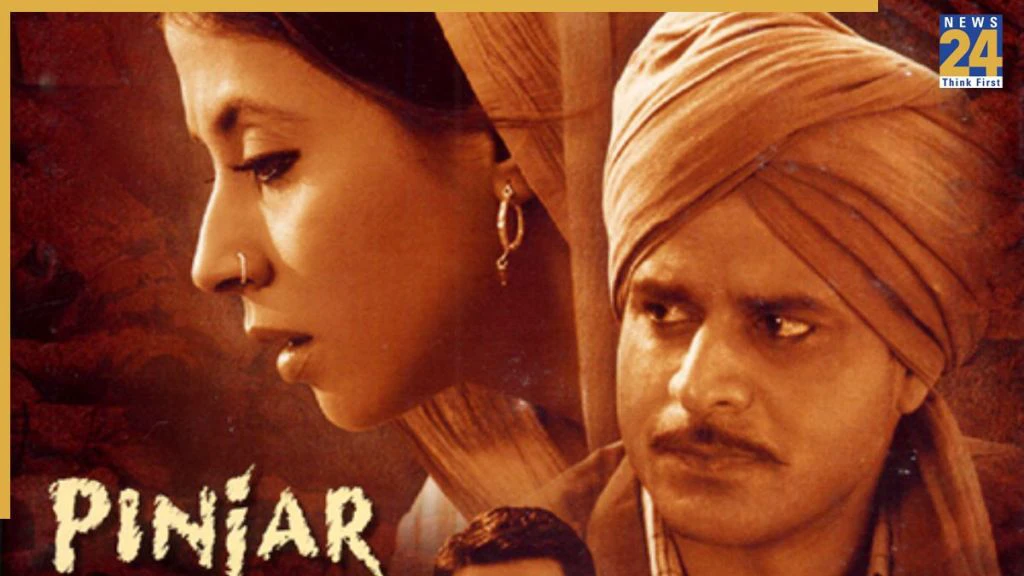

Why Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar?

I think our society needs to learn from its past mistakes. Take the Hindu-Muslim divide. I feel today our society is more communally fragmented than ever before. Why have our films refused to address this burning issue when our literature has dealt with the Partition from the time it happened? Sadat Haasan Manto wrote anti-Pakistan stories like ‘Khol Do’ even while living in that country. In that story, a Pakistani girl is gangraped by Pakistani men. Our Cinema has never really attempted to deal with contemporary problems or with history. That’s why mainstream Hindi cinema is so alienated from social reality. Hardly any films on the Partition!

How do you explain this lacuna?

Filmmakers are a frightened lot. When we were celebrating 50 years of Partition, a lot of thinkers wondered whether it was right to divide India into two. There’s a three-nation theory whereby the Christians, too, deserve their own nation. I firmly believe religion can’t keep people together. If it could, Bangladesh wouldn’t have happened. So what keeps a nation together? I feel only two films have so far addressed themselves to the Partition seriously. They’re M.S Sathyu’s Garam Hawa and Govind Nihalani’s Tamas.

And Pinjar is the third?

The Partition is only a part of Pinjar. I’m looking at a larger picture. People don’t want to look at the truth because they’re scared. The fact is, Hindu-Muslim relations were severely affected after the demolition of the Babri Masjid. My Muslim friends who worked with me on Chanakya left me after the demolition. It made me think. Why did the broad-minded intelligentsia become segmented. Even those Muslims whose roots are firmly in India began talking about settling abroad. Aisa kyon hua? These thoughts haunted me. Why has my Muslim friends become estranged from me? Why are there segregated schools for Muslim children in this country? As I see these children walk to school, I wonder why can’t these children study with their Hindu brothers? I ask this in the light of the fact that I’ve been projected as pro-Hindu in the media.

Aren’t you?

I am not. I remember when I was looking for a home in Mumbai, I was told to make sure it’s in a locality with a negligible Muslim community. I feel if Hindus distrust Muslims to this extent, then the feeling must be mutual. I had never seen communal riots in Mumbai before 1992. I began researching on the Partition. I read a true story about a Gujarati woman who waited 40 years for her husband to return from Pakistan. I became interested in the stories of Saadat Hassan Manto. Then I came across Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar.

How did she agree to let you film it?

I sent my assistant to her. When I went to her, she readily allowed me to film Pinjar. She told me I was the first person from the Mumbai film industry to fulfil my financial obligation, and that even if I hadn’t paid up, she’d have still parted with filming rights. The minute I finished the novel, I realised it went far beyond the Partition. Pinjar speaks about the Hindu-Muslim mindsets. I wanted to film a story which my daughter would grow up and feel proud about. I feel it’s time for the Mumbai film industry to stop believing that cinema has no connection with real life.

What do you think of Anil Sharma’s Partition saga, Gadar?

Everyone knows it clicked. But I feel it had too much Pak-bashing in its agenda. This country has a population of Hindus and Muslims, and it’s not two religions that are in conflict. We fail to see riots as a crime against mankind. When there’s an atrocity against mankind in the US, the entire world protests. Why not in this country? Literature and cinema need to bring crimes against civilisation to light. Pinjar talks about a time when there were separate water taps for Hindus and Muslims. What happens when a clean-hearted Muslim is compelled to abduct a Hindu girl? Do you know that after the Partition violence, thousands of Indian and Pakistani girls were returned to the opposite country. Thousands of others simply vanished.

Why did you select Urmila Matondkar for the main part?

I’d say she’s the female Naseeruddin Shah. When I decided to cast her, lots of people objected, saying there’s nothing suitable in Pinjar for her. I had never seen Urmila in any film, only in television clippings. Like Naseer, she can breathe life into the most inert lines. That’s why I chose her. Admittedly, I went to other actresses who also said yes. But Urmila was the most enthusiastic. Her eagerness is quite overpowering. She knew the script by heart. She knew everything about her costumes and lines.

How did you find the right architecture?

We couldn’t shoot in Punjab because the architecture there no longer resembles anything from the 1950s. We therefore shot in a place called Ganganagar which is on the Rajasthan-Punjab border. I went there because one couldn’t see electricity poles for miles. We went to Surat for the sugarcane fields.

Do you think Pinjar was too controversial?

I don’t think so. Pinjar has sided with neither Hindus nor Muslims. Whatever Amrita Pritam has dared to say in the novel has been put across in my film. So many works of literature have been attempted on the Partition. Why not cinema? I believe one must live and die for one’s beliefs. I can’t turn back. No compromises for me.