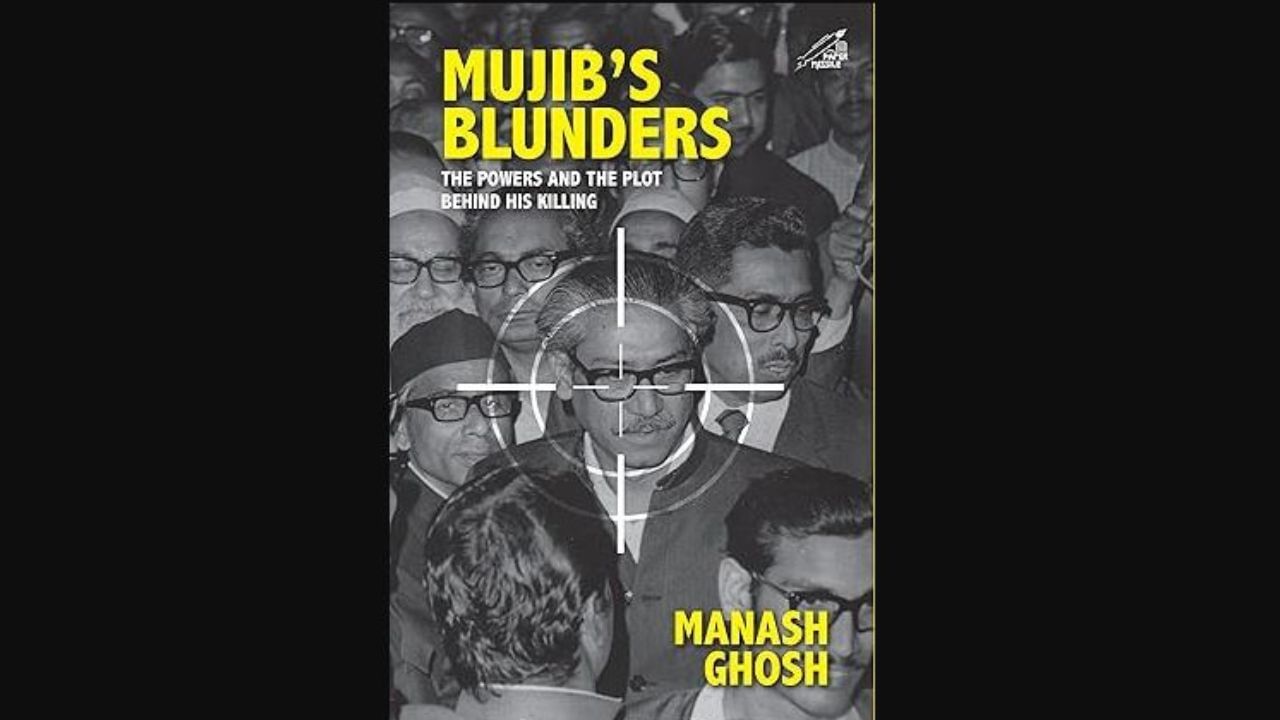

All heroes have metaphorical clay feet and it is good that Manash Ghosh has exposed the failings of Mujibur Rahman, inspiration and leader in absentia of the Bangladesh struggle for independence from Pakistan in 1970-71 and later prime minister and president of the country. It is a fitting rejoinder to the efforts by his daughter Sheikh Hasina, until recently prime minister to endow her father and other family members with superior virtues, attempts that have been overturned by Hasina’s overthrow for despotism and abuse of human rights by a popular movement.

Manash Ghosh is the foremost Indian chronicler of Bangladesh history starting with the liberation struggle narrated in his work Bangladesh War; Report from Ground Zero. In the early days of independence (1971-4), he was a newspaper correspondent in Dacca and was able to observe the personality and judgement failings of Mujib and those around him. Like many before him Mujib was a brilliant opposition leader but poor administrator and poorer judge of character, a gullible victim to growing plots around him. He compounded these failings by a magnified over-confidence in his own charisma and connect with the Bangladeshi people. His setting up a one-party state with himself at its head was the last straw for his multiple adversaries and there were few at home or abroad, other than India, that were distressed at his downfall.

Mujibnagar, headquarters of the liberation struggle, was a divided house, with crypto pro-Pakistanis, and other dissenters. Among these was Khondokar Mushtaq hardly hiding his opposition to Tajuddin leading the interim government in exile, despite Tajuddin’s success in ‘cobbling up an administrative structure for the government in exile almost out of nothing and that too on foreign soil with very little talent and extremely limited human resources.’

After the joyous inception of the new nation, fissures appeared. By 1972 when famine and shortages stalked the land, Ghosh observed rising anti-Indian and anti-Hindu opinion; the secular minded were few; pro-Pakistan Islamic circles made allegations, sometimes true, of imported shoddy overpriced Indian goods and Indian exploitation. Actions by the liberating Indian army, smuggling from India and former Indian owners attempting to reclaim ancestral land were denounced and rumour and prejudice were rife. Ghosh writes, “Except Tajuddin, none in the provisional government had a good word for the Indian gesture’ of sending thousands of tons of essential commodities.

Mujib showed scant interest in the nine-month liberation war that led to his release from Pakistan and leadership of the new country and refused to visit the place where in April 1971the provisional government was established. Tajuddin bewailed, ‘During my hour-long meeting with [Mujib] he never asked me how in his absence, I provided the leadership to the Liberation War and led it to its successful conclusion.’

Wanting Mujib’s support, Tajuddin’s proposals for building the country were denounced as yielding to India. Efforts by India to restore some damaged infrastructure were condemned as sub-standard. Anti-Indian sentiment grew even among the masses ‘with Mujib and his government aiding and abetting this to grow unhindered.’ Anti-Indian feelings were seeded by pro-Pakistan and pro-Chinese circles and a local journalist told Ghosh that ‘Mujib’s overconfidence that he can deal with these inconsequential elements is somewhat foolhardy and misplaced.’ Ghosh adds that ‘the tragic part of Mujib’s character is … that he could clearly read the writing on the wall [but] did nothing to forestall the worst-ever political assassination in August 1975…and four senior members of his party [including Tajuddin] inside Dacca jail three months later.’

Mujib placed his and the nation’s enemies in key positions in governance, asserting he was against vendetta politics, trusting that being humane would inspire a change of heart. He gave opponents like Khondokar Mushtaq portfolios with the justification of keeping an eye on them. On the other hand, he never welcomed any ‘loyal opposition’. New Delhi also ‘lacked clarity in its policy towards securing the life and property of minorities in Bangladesh.’

Mujib underestimated the strength of communal elements; he released Muslim League and Islamist Pakistani collaborators, officers and men from Pakistani army and intelligence were repatriated without screening and given equivalent employment despite hardly concealed hostility to Mujib’s secular Bengali nationalist approach. Army indiscipline and corruption and inter-se hostility in his administration were rife. Mujib setting up para-miliary forces to tackle law and order upset the army. Mujib termed the unfolding chaos as ‘disruptive politics’, adding ‘I know who all, including some of my ministers, are behind…this conspiracy’. But he did nothing about it and Tajuddin who might have addressed the situation, was progressively stripped of important functions; his critics in the circle around Mujib alleged that he had antagonized USA, Pakistan and China even as Mujib wanted to distance himself from India and USSR, becoming increasingly pro-Chinese though it was blocking Bangladesh’s admission to the UN.

In early 1975 Mujib moved to one-party rule with his new party Baksal. ‘I felt’, writes Ghosh, ‘that Mujib had been overtaken by a death wish.’ Mujib’s administration was ‘an epitome of misrule and endemic corruption’. He ignored multiple foreign and local warnings about traitors; and specifically, about being killed. What was increasingly ‘clear as daylight’ to Ghosh, was also for the few remaining Mujib loyalists. The Bulgarian ambassador knew about the plot in some detail, so must the Soviet envoy. Rahman Sobhan’s recent memoir clearly implicates the US in Mujib’s killing; there was no pro-Mujib counter coup and his eventual successors Zia and Ershad eliminated the remaining freedom fighters in the army.

The book lacks an Index, table of acronyms, and a list of characters for this 50-year-old history, as also a timeline of events. More dating of events, even just the year, would have been useful. Ghosh’s intellectual investment in Bangladesh is clear, but his objectivity might be in question, especially in the Epilogue on Hasina’s downfall that is out of place here, and his assessments eliding the various excesses that many observers believe led to her self-exile. On the other hand, the book has a reader-friendly typeface, few typos and interesting photo pages in this eloquent and detailed exposition of the perils of political over-confidence.