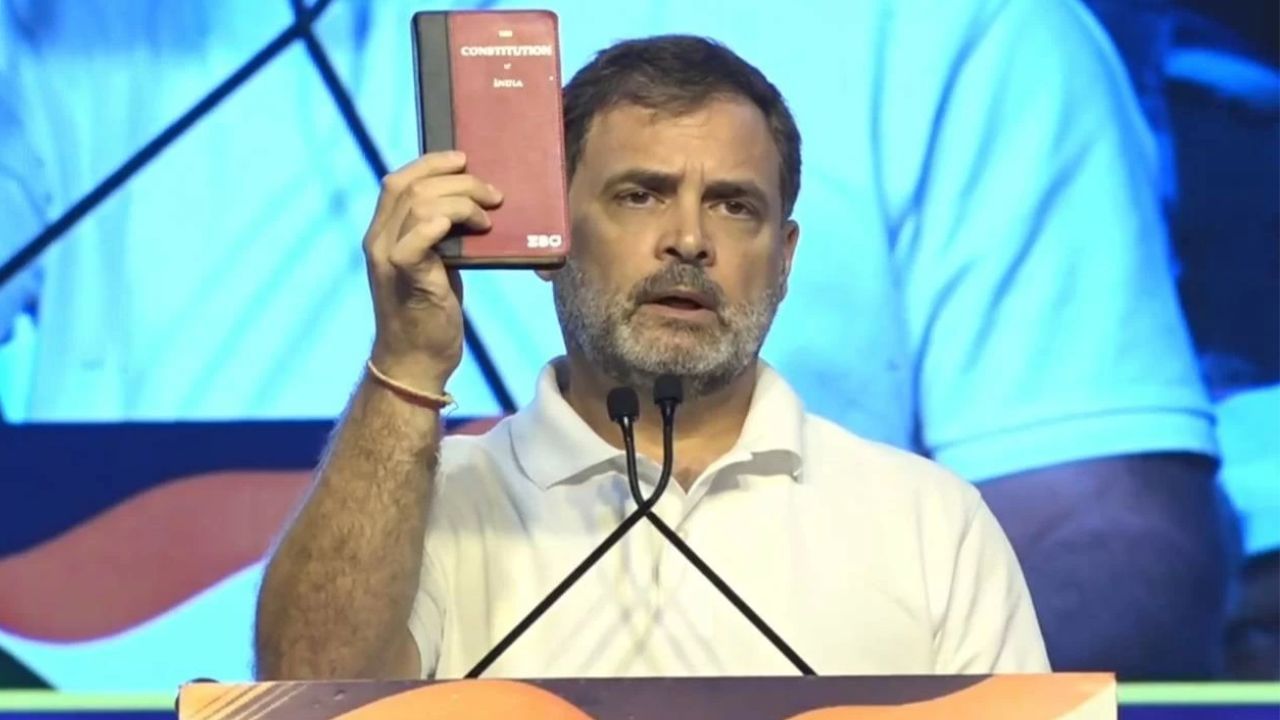

New Delhi: Mahadevapura, a bustling hub in east Bengaluru home to hundreds of IT companies—from coding shops to cutting-edge research labs—shot into Google search trends earlier this week thanks to Opposition leader Rahul Gandhi. Mimicking a corporate-style pitch, Gandhi stood before reporters in Delhi with a PowerPoint presentation, alleging that “vote theft” took place in the constituency during the 2024 parliamentary elections. He claimed the Election Commission, in collusion with the BJP, engineered the outcome. “It’s an open-and-shut case. Here is the evidence,” he declared, before receiving applause that night from INDIA bloc leaders at a dinner hosted at his residence for, as they put it, “exposing the BJP–ECI nexus.”

This was hardly the first time Gandhi had raised such allegations. In recent years, he and other INDIA bloc leaders have repeatedly accused the BJP of winning parliamentary elections since 2014 through EVM tampering—a claim dismissed by the Supreme Court, forcing Gandhi to recalibrate his narrative. After the Maharashtra polls, he returned to pursue the same narrative, claiming to have found “goldmine” evidence of vote theft. Soon after, came the SIR exercise from Bihar, giving the Opposition fresh ammunition against the Election Commission. The matter has since reached the Supreme Court, where a hearing is pending.

The twist this time was Gandhi’s decision to focus on a single constituency. His team pored over the electoral rolls of Mahadevapura, highlighting the alleged inconsistencies and variations to argue that the BJP–ECI nexus was at play. That’s how the locality became a trending topic on X and Google.

The campaign has two clear strands—political and legal. More than a year had passed since the 2024 elections, yet no state Congress leader had raised these concerns until Gandhi’s presentation. Only then did Karnataka’s top leaders, including Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and Deputy CM D.K. Shivakumar, publicly join the chorus.

Electoral Rolls – Inconsistencies?

Before analysing the pattern of errors in the voters’ list, it’s worth recalling how an eligible voter gets into the electoral roll. Imagine you move to Mahadevapura in Bengaluru with no credible document in your name. You take a flat or a single BHK house there and in the process, you will get a rent agreement in your name. After three months at your new address, you’re eligible for a cooking gas connection based on that rent agreement witnessed and signed. With the new gas connection in place, you can apply for an Aadhaar card. Utility bills of gas, electricity, or telephone connections, from the past three months are considered as proof for issuing Aadhar.

Anyone staying here, including people from neighbouring countries, can follow this route. Once you have Aadhaar, enrolling in the voters’ list is straightforward. But if the address and spelling of your name in the rent agreement is wrong, that error will cascade through every subsequent document issued by various authorities.

When I lived in one of Bengaluru’s older areas, workers from both Congress and BJP approached me, offering to help me get onto the voters’ list. Their role? Collect hard copies of documents, make repeated trips to the Bengaluru Corporation office, and ensure the name is enrolled after completing the formalities. Once your name is on the list, there’s no trace of which party worker helped you get there.

So how can Mr Gandhi claim that specific names appear on the list solely because of BJP influence? Helping someone get registered might be considered “soft canvassing,” but it doesn’t guarantee that person will vote for the party whose workers assisted them.

Now, back to the crux: variations and errors in electoral rolls are nothing new. Political scientist and psephologist Sandeep Shastri, citing data from Janagraha (an urban studies NGO), wrote a column in an English daily saying that such inconsistencies were present 16–17 years ago. That means, this menace was there even during the UPA regime. Public apathy with respect to having a robust voters’ list has persisted: people register in multiple locations without much thought, fail to remove their names after moving, and don’t inform the Election Commission about the deaths of relatives. The process is so tedious that many avoid it entirely.

Even if we accept Mr Gandhi’s claim that the surge in new voters in Mahadevapura is unusual, how can we assume they all back the BJP? What if some voted for Congress? The same logic applies to deletions—how can we be certain they disproportionately affected Congress supporters? Likewise, how do we prove that names with similar photos are part of a BJP-led strategy? And why should we believe that so-called “ghost voters” voted only for the BJP?

Political angle

There’s more to the Mahadevapura “vote theft” case than what meets the eye—and it’s a point, few have noticed. First, how did Rahul Gandhi’s team zero in on Mahadevapura? It appears likely they analysed Congress defeats in constituencies with high minority voter populations. Bengaluru Central comes in that category and this constituency alone has over six lakh minority votes. Losing such a constituency would naturally sting Congress leaders. That makes Mahadevapura—a BJP stronghold that contributed to the BJP’s win in Bengaluru Central—a strategic choice for scrutiny.

This may explain the subtext of Gandhi’s Delhi press conference. Officially, it was about “vote theft.” But behind the scenes, the bigger question for Congress was: Despite high minority turnout, how did the BJP win this seat? In that light, Gandhi’s public call to citizens looked more like political signalling than the presentation of airtight evidence.

Any academic would resist taking an “open-and-shut case” at face value. A closer look at Mahadevapura’s rolls naturally invites comparisons with other Bengaluru Central assembly segments: Sarvajna Nagar, Shanti Nagar, and Chamarajpet. Unlike Mahadevapura—which has been with the BJP since 2008—these three have been Congress strongholds since the 2008 delimitation exercise.

What if the same kind of errors found in Mahadevapura’s voter rolls, also exist in Sarvajna Nagar, Shanti Nagar, and Chamarajpet constituencies dominated by minority votes? And all the three are being held by Congress legislators. Can we still call it “vote theft” by the BJP? Without examining these three segments, any conclusion based solely on Mahadevapura is incomplete.

New CEO for Karnataka

Meanwhile, V. Anbukumar, a 2004-batch Karnataka cadre IAS officer, took charge as Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) of Karnataka last month, succeeding Manoj Kumar Meena, who held the post for four years. During Meena’s tenure, Karnataka saw the 2023 assembly elections—when Congress swept to power with 136 seats—and the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, in which Congress won 9 of 28 seats, while the BJP–JD(S) alliance secured the remaining 19.

If Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and Deputy CM D.K. Shivakumar truly accept Rahul Gandhi’s claim that “vote theft” occurred in Mahadevapura and that it’s an “open-and-shut case,” does that imply they believe former CEO Meena failed to ensure free and fair polls? With Mr Gandhi now urging the state government to investigate the Mahadevapura case, can the Karnataka government hold Meena accountable for the alleged irregularities—despite him now serving once again under them?

Would senior bureaucrats, including Chief Secretary Shalini Rajneesh, approve such a move if the CM pursued it? How would the Karnataka chapter of the IAS Officers’ Association respond? And could they realistically challenge the CM and DCM if disciplinary action was initiated against Meena?

Delimitation Conundrum

A final piece of political grapevine offers a sobering backdrop to the very creation of Bengaluru Central—and other such constituencies—created during the 2006 delimitation exercise. A former home minister, who had served under H.D. Deve Gowda and attended meetings of the Delimitation Commission, once shared an intriguing account: two senior figures—one from Congress and the other from the Janata Parivar—allegedly worked together to shape assembly constituencies in ways designed to disadvantage the BJP in future elections. This strategy, he claimed, influenced the formation of at least 25 assembly segments in Karnataka.

Take Chamarajpet and Bharati Nagar (now Sarvajna Nagar) as examples. Before delimitation, the BJP had won both seats. Afterward, the new constituency boundaries incorporated enough minority voters to decisively influence outcomes—effectively ensuring BJP defeats in these areas.

In this context, Mr Gandhi appears to have political harvest by exploiting the erroneous system. But his current claim rests on shaky ground. Without hard evidence of collusion or theft, the allegation is weak and unlikely to survive legal scrutiny.