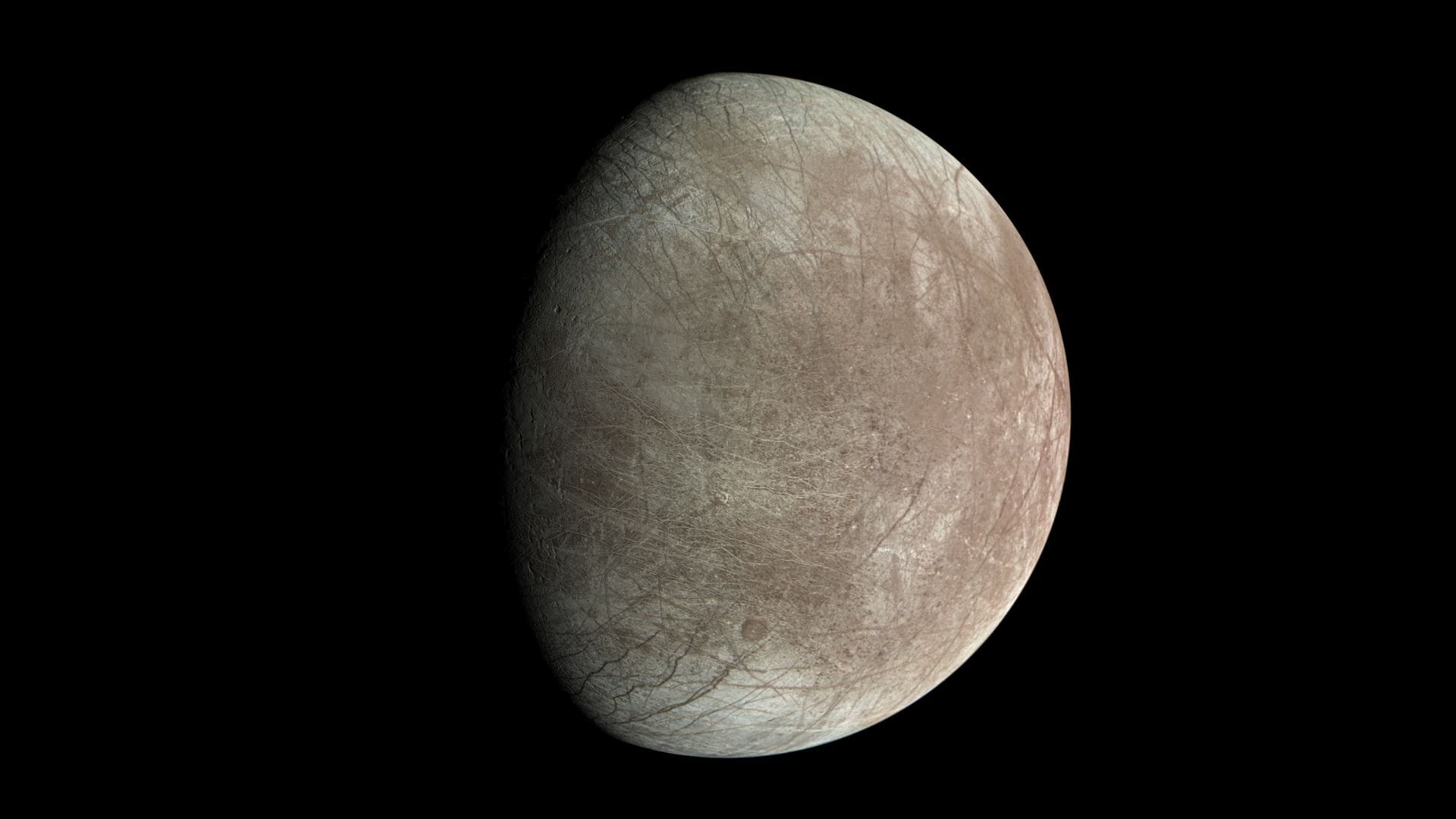

New Delhi: NASA’s Juno spacecraft, the most distant operational planetary orbiter has provided a new measurement of the ice shell on the Jovian moon of Europa. Data from the Microwave Radiometer (MWR) on the spacecraft collected during a close flyby on 29 September, 2022 was used to measure the ice shell. The observations indicate that the shell averages 29 kilometres in thickness in the observed region. The observations resolve prior uncertainty, with models indicating a thickness between less than one kilometre to tens of kilometres. The MWR was originally built to probe the thickness of Jupiter’s dense atmosphere, and not measure the thickness of Europa’s ice shell.

Scientists measured the microwave emissions to determine the subsurface temperatures at various depths, covering roughly half of the surface of Europa. The 29 kilometre estimate applies to the cold, rigid, thermally conductive outer layer of pure water-ice. There may be a warmer, convective layer beneath, which means that the total shell thickness would be greater. Models that include a modest amount of dissolved salt in the ice shell would reduce the estimated thickness by about five kilometres. A thicker ice shell means a longer pathway for oxygen and other surface materials to reach the global subsurface saltwater ocean.

A potentially habitable world

The deep global subsurface saltwater ocean makes Europa one of the most promising environments in the solar system to discover extra-terrestrial life. Europa is slightly smaller than the Moon of the Earth, and is one of the highest-priority targets for astrobiological research. The MWR data also reveals small-scale irregularities in the near-surface ice. These are features such as cracks, pores and voids that are up to a few centimetres across, that extend to depths of hundreds of metres, but appear too limited in size and extent to act as significant conduits for material exchange between the subsurface ocean and the surface. A paper describing the research has been published in Nature Astronomy.