Dwarkanath Ganguly, a schoolteacher, social reformer, and crusader against gender injustice and British exploitation, remains one of the largely forgotten pillars of the Indian Renaissance.

Dwarkanath Ganguly, a schoolteacher, social reformer, and crusader against gender injustice and British exploitation, remains one of the largely forgotten pillars of the Indian Renaissance. The Renaissance in India found its earliest momentum in the Brahmo Samaj, founded by the visionary Raja Rammohan Roy. While Roy’s legacy is widely celebrated for championing women’s emancipation and education, few remember the radical Brahmo who fearlessly exposed the brutal exploitation of Indian laborers under British rule: Dwarkanath Ganguly.

Born in April 1845 in Magurkhanda village, Bikrampur district, Dwarkanath’s formative years were profoundly influenced by Akshay Kumar Datta’s thesis on the plight of Indian women: “The first vital step to social regeneration is liberating woman from her bondage.” As a teacher in British Bengal, he transformed his convictions into action, launching the weekly magazine Abalabandhab (Friend of Women) to shine a light on women’s suffering and exploitation. As historian David Kopf noted, “This journal was probably first in the world devoted solely to the liberation of women.”

Dwarkanath’s radical ideas stirred debates within the Brahmo Samaj, often clashing with conservative voices. He served multiple roles at Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya — later renamed Banga Mahila Vidyalaya and merged with Bethune School — as headmaster, teacher, maintenance man, guard, and sweeper. In a remarkable historical footnote, he is also the great-grandfather of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

Dwarkanath married Kadambini Basu, one of India’s first women graduates and among South Asia’s pioneering female physicians trained in Western medicine. David Kopf observed, “Kadambini was, appropriately enough, the most accomplished and liberated Brahmo woman of her time.” When societal backlash threatened her ambitions, Dwarkanath stood unwaveringly by her, famously confronting a periodical editor who called her a courtesan — even going so far as to make him swallow the offending article and later ensuring his imprisonment and fine.

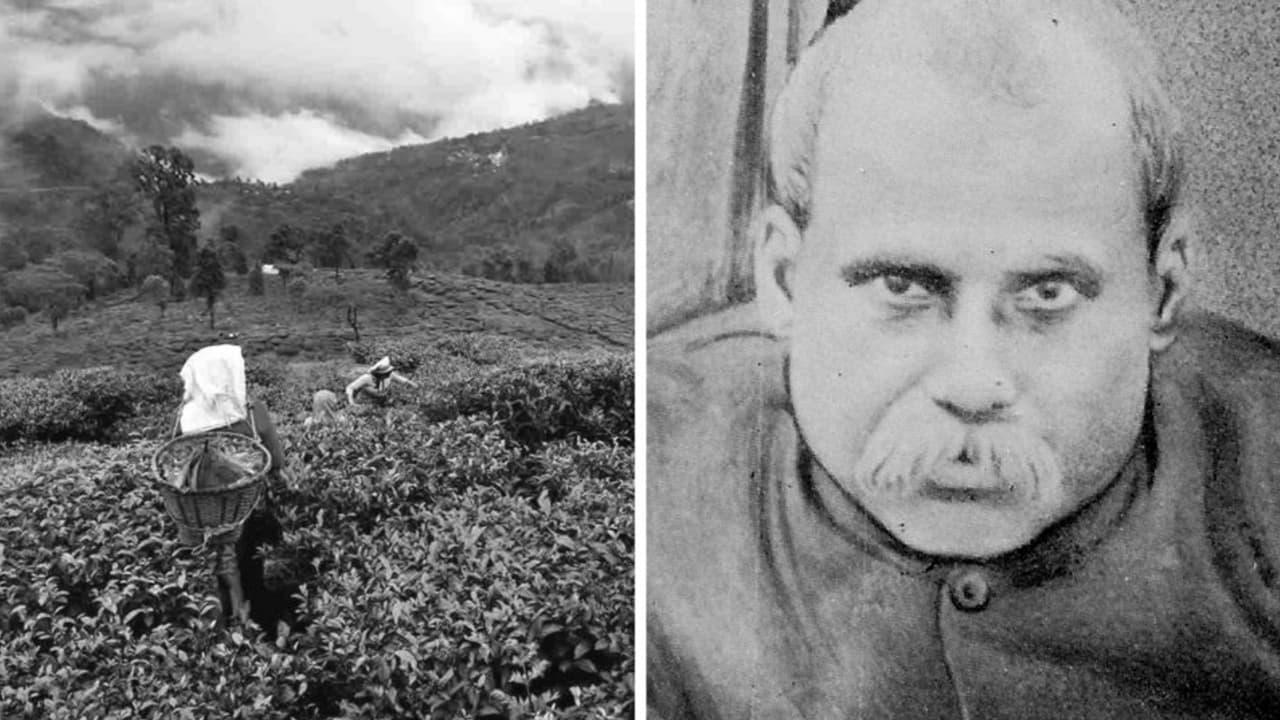

Dwarkanath’s relentless fight for justice extended far beyond gender issues. His humanitarian vision encompassed the downtrodden and marginalized, and he used his writing to expose systemic exploitation. Most notably, he investigated the appalling conditions of indentured laborers — known as “coolies” — in Assam’s tea plantations.

Introduced by the British in the 1830s, these indentured labor contracts promised livelihoods but trapped workers in near-slavery, penalized by harsh laws if they attempted to leave. Disturbed by firsthand accounts of addiction, abuse, and oppression, Dwarkanath risked his life to traverse inaccessible plantation regions, confronting the stark inequalities of “Planter’s Raj.”

His exposes, published in nationalist newspapers such as Sanjibani and Bengalee, laid bare the exploitative system: abysmally low wages, brutal punishments, and staggering mortality rates, with one in four workers perishing under the oppressive regime. Dwarkanath’s tireless activism reached the Indian National Congress, mobilizing leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal to investigate and challenge the imperial system.

The ripple effects of his reporting were profound. By the early twentieth century, Dwarkanath’s revelations had become central to nationalist agitation against colonial exploitation, ultimately contributing to the abolition of the indenture system in 1920.

(This article has been curated with the help of AI)