Revered as one of history’s greatest literary figures, Tolstoy’s profound philosophy left an indelible imprint on the young Gandhi, nurturing his ideals of Ahimsa, Satyagraha, and Swadeshi.

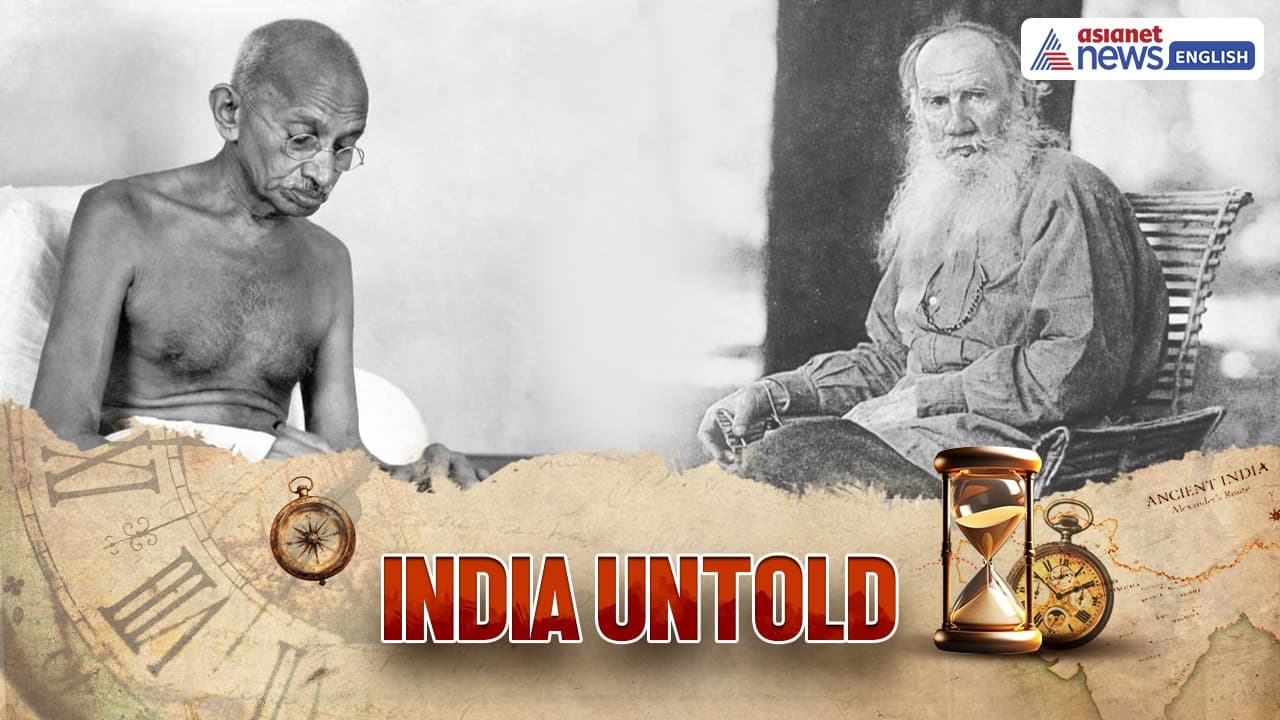

Long before Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi emerged as the indomitable force of India’s freedom struggle, he found a guiding light in the words of the Russian literary colossus, Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. Revered as one of history’s greatest literary figures, Tolstoy’s profound philosophy left an indelible imprint on the young Gandhi, nurturing his ideals of Ahimsa, Satyagraha, and Swadeshi.

Gandhi himself described Tolstoy as the “greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age had produced” and “a great teacher whom I have long looked upon as one of my guides.” Reflecting on the Russian’s work, he once said, “Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You overwhelmed me. It left an abiding impression on me.” The book, he noted, championed independent thinking and truthfulness, cementing his lifelong commitment to non-violence.

Their correspondence, initiated in 1908 through the efforts of Indian revolutionary Taraknath Das, became a profound exchange of ideas that would endure until just weeks before Tolstoy’s death on 7 November 1910. Gandhi’s South African publication, Indian Opinion, played a pivotal role in this dialogue, publishing Tolstoy’s seminal letter as A Letter to a Hindu.

What Tolstoy Wrote in His Letters to Gandhi

In these letters, Tolstoy denounced centuries of violence that humanity had accepted as necessary, framing it as a deviation from the natural “law of love.” As Maria Popova observes, “Tolstoy’s letters issue a clarion call for nonviolent resistance. He admonishes against false ideologies—both religious and pseudo-scientific—that promote violence… Evil, Tolstoy argues with passionate conviction, is restrained not with violence but with love — something Maya Angelou would come to echo beautifully decades later.”

Tolstoy’s message: “It is natural for men to help and to love one another, but not to torture and to kill one another.” He urged Gandhi to see love, not force, as the only path to liberation. “Love is the only way to rescue humanity from all ills, and in it, you too have the only method of saving your people from enslavement… Love, and forcible resistance to evil-doers, involve such a mutual contradiction as to utterly destroy the whole sense and meaning of the conception of love.”

Tolstoy even analyzed colonial oppression, “What does it mean that thirty thousand men, not athletes but rather weak and ordinary people, have subdued two hundred million vigorous, clever, capable, and freedom-loving people?… If the people of India are enslaved by violence it is only because they themselves live and have lived by violence, and do not recognize the eternal law of love inherent in humanity… As soon as men live entirely in accord with the law of love natural to their hearts… not even millions will be able to enslave a single individual.”

In one of his final letters on 7 September 1910, Tolstoy reinforced his lifelong conviction, “The longer I live — especially now when I clearly feel the approach of death — the more I feel moved to express… what we call the renunciation of all opposition by force… Love, or in other words the striving of men’s souls towards unity… represents the highest and indeed the only law of life… Any employment of force is incompatible with love.”

Gandhi recognized the depth of Tolstoy’s insight, especially his reflections as a soldier in the Crimean War. In introducing A Letter to a Hindu, Gandhi cautioned against replicating colonial violence: “India, which is the nursery of the great faiths of the world, will cease to be nationalist India… when she goes through the process of civilization in the shape of reproduction on that sacred soil of gun factories and the hateful industrialism… If we do not want the English in India we must pay the price. Tolstoy indicates it: Do not resist evil [with violence], but also do not yourselves participate in evil…”

Tolstoy’s influence transcended words. Gandhi and his friend Hermann Kallenbach named their South African farm Tolstoy Farm in 1910. The farm became the epicenter of Satyagraha campaigns, promoting self-sufficiency, non-violence, and truthfulness. Experiences here directly informed Gandhi’s Swadeshi Movement, emphasizing indigenous goods and self-reliance.

Reverend Joseph Doke, Gandhi’s first biographer, observed, “Undoubtedly Count Tolstoy has profoundly influenced him… The old Russian reformer, in the simplicity of his life, the fearlessness of his utterances, and the nature of his teaching on war and work, have found a warmhearted disciple in Mr Gandhi.”

(This article has been curated with the help of AI)