In a world where being a cinematic star was a rare and celebrated feat for a woman, Arundhati Devi (1924-1990) was an exception, as she denied the status and lifestyle of a conventional ‘star,’ despite appearing in nearly 35 Bengali films between the 1950s and the 1980s.

Arundhati wore multiple hats within the domain of cinema, as writer, singer, actress, producer and director, each with serious involvement and dedication. Her life generated an archive of photographs, working scripts and correspondences, booklets, posters, lobby cards, and of course films, many of which are housed in her family’s residence in Kolkata. An exhibition celebrating the myriad filmic contributions of this ‘star’, reluctant as she was to be called as such, is currently on view at the art gallery of the Kamaladevi Complex, India International Centre. Curated by Mrinalini Vasudevan and Tapati Guha-Thakurta, this is a rare exclusive show devoted to an Indian actress.

Arundhati with her friends in Santiniketan, January 1941. Photograph: Shambhu Saha. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati with her friends in Santiniketan, January 1941. Photograph: Shambhu Saha. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

The exhibition opens with an introduction into Arundhati’s early childhood in Dhaka, her life in the large and illustrious Guha-Thakurta family, her Shantiniketan education, her first marriage to Prabhat Mukherjee (assistant station director of AIR Calcutta) and her role as mother to Anuradha and Anindya. The photographs and a diary from this period are from private albums, supplemented by letters and oral recollections. Having trained extensively in Rabindrasangeet at Shantiniketan, Arundhati’s first foray into the world of performance was through radio and stage singing, marked eminently by the songs she sang for Gandhi in 1946.

Arundhati’s time in mainstream cinema coincided with a newly independent India of the 1950s and ’60s. She had the transformative opportunity of traveling to the United States in 1952, as part of a delegation of representatives from the Indian film industry. In these photographs, she is seen posing with well-known actors such as Raj Kapoor, Nargis, Prem Nath, Bina Rai and others in the studios of Hollywood. She is wearing elegant saris with hand-embroidered bags and capes, some of which still remain in the family’s personal collections. She minutely observed the advances made by American cinema, and the wall text quotes her being enamoured by their use of “make-up to build characters and bring alive historical figures.”

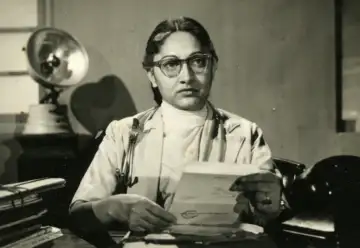

Arundhati in Chalachal (dir. Asit Sen, 1956). Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati in Chalachal (dir. Asit Sen, 1956). Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati’s early exposure to world cinema on the one hand, and diverse urban and vernacular life on the other, shaped her sensitivity to the many roles of women in an emerging nation. She portrayed a range of feminine archetypes, such as the wife – in Nad o Nadi (directed by Chitta Bose, 1954); Sati (directed by Aar Mullick, 1954) and Godhuli (directed by Kartik Chattopadhyay, 1955) – and the professional woman – in Chalachal (1956) and Panchatapa (1957), both directed by Asit Sen. These contrasted with more individualised characters, such as the Catholic heroine in Bhagini Nibedita (directed by Bijoy Bose, 1962, winner of the President’s Award for Best Film) and Manmoyee Girls School (directed by Hemchandra Chandra, 1958), the vivacious, liberated Brahmo woman in Bicharak (directed by Prabhat Mukherji, 1959), and the mystery girl in Dasyu Mohan (directed by Ardhendu Mukherjee, 1955) and Indradhanu (directed by Dipak Bose, 1960). These roles saw Arundhati’s versatility shine through in her appearance, costumes, dialogue delivery and acting. After her a second marriage to director Tapan Sinha, she enjoyed even greater freedom in interpreting and playing a number of challenging roles, for which she came to be best known.

Arundhati with Tapan Sinha, possibly on the sets of Kalamati, c. 1958. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati with Tapan Sinha, possibly on the sets of Kalamati, c. 1958. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati’s contributions as a director and producer in her later life added new facets to her career, even though she had to constantly fight the public perception of her work being largely influenced and supervised by Tapan Sinha. She deftly managed large teams on outdoor shoots and unusual cinematic choices. She was particularly interested in the fragility and complexity of young lives and relationships, captured through music and memories and a frank exchange of conversations and gazes against the backdrop of nature. This evocative quality is particularly evident in her directorial debut Chhuti (1967) – about a young woman’s struggles with terminal illness while discovering new love – which won her a National Award for Best Film Based on High Literary Work. She even asserted her creative rights by fighting a legal case with her co-producer, R.D. Bansal, and removing her name as director from Dipar Prem (1984), when she disagreed with him on the film’s ending.

Arundhati directing during the shoot of Chhuti, 1966. Photograph: Sukumar Roy. Courtesy: Suranjan Roy.

Arundhati directing during the shoot of Chhuti, 1966. Photograph: Sukumar Roy. Courtesy: Suranjan Roy.

Arundhati receiving the National Film Award for Chhuti from President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, 1967. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Arundhati receiving the National Film Award for Chhuti from President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, 1967. Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

In a lineage of women actresses from East India, Arundhati Devi held her own ground in contrast to the more glamorous Suchitra Sen, Sharmila Tagore and Moushumi Chatterjee, who migrated into mainstream Hindi cinema. Her only Hindi film was Yatrik, the remake of her debut film Mahaprasthaner Pathey (directed by Kartik Chatterjee, 1952), where she played a widow on a pilgrimage to Kedarnath and Badrinath. Yet her cinema addressed a wide audience as she touched upon a range of social and personal issues that confronted the newly constituted female citizen of India.

Arundhati with Uttam Kumar in Bicharak (dir. Prabhat Mukherjee, 1959).

Arundhati with Uttam Kumar in Bicharak (dir. Prabhat Mukherjee, 1959).

Courtesy: Arundhati Devi Family Archive.

Her work behind the camera puts her in the same lineage as other older and contemporary women figures such as Kanan Devi, Pratima Dasgupta, Manju Dey, Jaddan Bai, Shobhana Samarth and P. Bhanumathi, who were gradually making inroads within male-dominated industries. Many of the works produced by these early female filmmakers have been lost, making it all the harder to rediscover these legacies. It has taken a new generation of feminist scholarship to unearth their stories and archives through the oral and material sources that survive, and one hopes that archival exhibitions such as A Star Named Arundhati will only pave way for throwing light on many such remarkable women artistes and practitioners whose biographies might otherwise be relegated into obscurity.

A Star Named Arundhati, curated by Mrinalini Vasudevan and Tapati Guha-Thakurta, is on display at the India International Centre, New Delhi till October 25, 2025.

Suryanandini Narain is assistant professor in visual studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University.