Decades-old barrels dumped off Southern California are leaking alkaline waste, not just DDT, creating ghostly halos on the seafloor. Scientists warn the toxic legacy is reshaping marine ecosystems and persisting far longer than expected.

For decades, strange white “halos” circling rusting barrels deep off the coast of Southern California puzzled scientists. Many believed the barrels contained DDT, the infamous pesticide once dumped into the Pacific in huge quantities. But new research reveals a different — and equally troubling — story.

Toxic Legacy Beneath the Waves

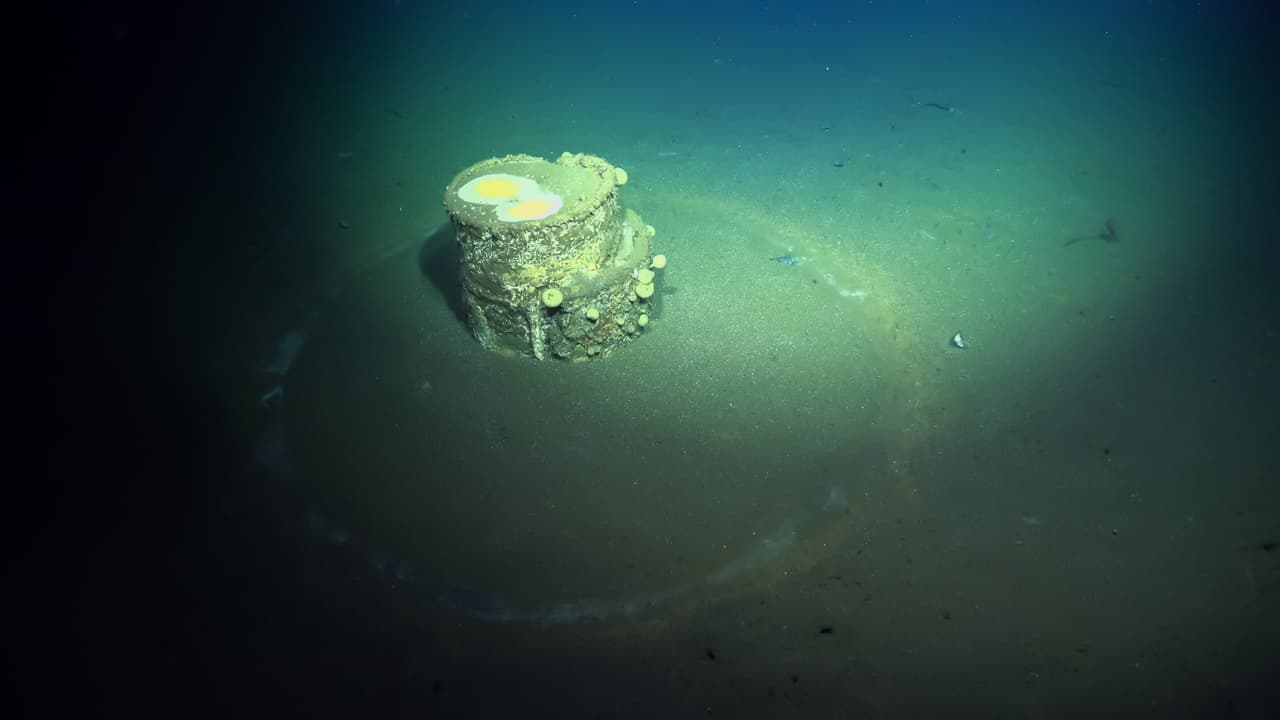

A team from UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography discovered that many of the barrels weren’t filled with DDT waste at all. Instead, they contained highly alkaline industrial waste that leaked into the surrounding sediment. This caustic material reacted with seawater minerals, creating concrete-like crusts and leaving behind eerie pale rings on the seafloor.

“The waste was so corrosive it essentially transformed parts of the ocean bottom into toxic vents,” said lead researcher Johanna Gutleben. “It’s remarkable — and disturbing — that the damage is still visible more than 50 years later.”

A New Kind of Seafloor “Vent”

The alkaline leaks didn’t just leave marks in the sand. They reshaped the ecosystem. Bacterial life in these areas now resembles microbes found in extreme environments like hydrothermal vents or alkaline hot springs — places where most marine life cannot survive. Animal diversity around the barrels also dropped sharply, signaling a broader ecological toll.

More Than Just DDT

For years, the spotlight has been on DDT, banned in 1972 after its harmful effects on humans and wildlife came to light. But this study highlights that DDT was only part of the dumping story. Oil refineries, chemical plants, and other industries also disposed of waste in these waters, leaving behind a toxic mix whose full composition is still largely unknown.

“This research shows that DDT wasn’t the only danger,” said senior author Paul Jensen. “The alkaline waste is just as persistent, and in some ways, more damaging than anyone expected.”

Still Visible After Half a Century

What shocked researchers most is the persistence of this waste. Many assumed alkaline byproducts would quickly dilute in seawater. Instead, the halos — and their environmental impact — remain strikingly intact after more than half a century.

The findings, published in PNAS Nexus, provide new tools for identifying contaminated barrels by their surrounding halos. Scientists hope this will speed efforts to map the scale of the problem, though the true number of barrels on the seafloor remains unknown.

A Warning for the Future

The eerie white rings serve as a reminder of the hidden costs of past industrial practices. As Gutleben put it: “We only find what we’re looking for. Until now, nobody was looking for alkaline waste. This is just the beginning of uncovering what else was left behind.”