Researchers from Stuttgart and Melbourne have created an “optical sieve” test strip that makes nanoplastic particles visible through striking color changes. This low-cost breakthrough could transform environmental monitoring and health research.

Nanoplastics — particles so small they can pass through human skin and even cross the blood-brain barrier — have long been nearly impossible to detect. Now, researchers from the University of Stuttgart in Germany and the University of Melbourne in Australia have unveiled a breakthrough method that makes these invisible pollutants visible using nothing more than a test strip and a standard microscope. Researchers have published their results in Nature Photonics.

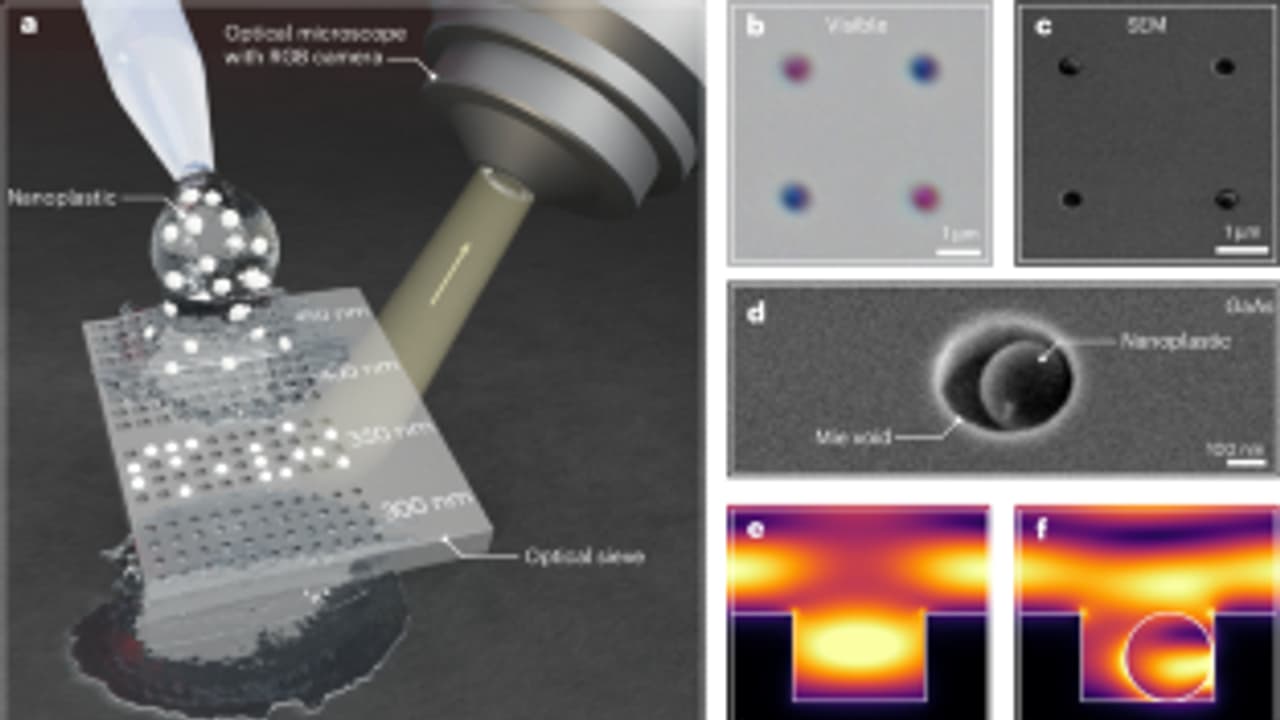

How It Works: An Optical Sieve

The tool, called an optical sieve, contains tiny holes etched into a semiconductor surface. When nanoplastics settle into these holes, the reflected color changes, creating a visible signal that reveals both the size and number of particles.

“Think of it like a sieve for light,” says PhD researcher Dominik Ludescher, lead author of the study published in Nature Photonics. “Particles too large are washed away, those too small don’t stick, and only those of the right size create the distinctive color change we can see under a regular microscope.”

A Cheaper, Faster Alternative

Until now, detecting nanoplastics required expensive, highly technical equipment like scanning electron microscopes. The new optical sieve method, by contrast, is inexpensive, easy to use, and far faster.

Dr. Mario Hentschel, who heads the Microstructure Laboratory at Stuttgart’s 4th Physics Institute, highlights its potential: “Our method could be used directly in the field, testing water, soil, or even biological samples for nanoplastic contamination without the need for specialized facilities.”

Why It Matters

Plastic pollution has long been recognized as a global crisis, with microplastics documented in oceans, rivers, and even human bloodstreams. But nanoplastics — far smaller fragments created as plastics degrade — are potentially even more dangerous because of their ability to penetrate deep into biological systems.

The new test strip could finally give scientists a practical way to measure these invisible threats in real-world environments and human tissue samples.

Next Steps

The Stuttgart-Melbourne team now plans to test the method with irregularly shaped particles and explore whether it can distinguish between different types of plastic. They are also seeking collaborations with environmental researchers to trial the sieve on real water samples, beyond laboratory-controlled conditions.

If successful, the optical sieve could become a simple, mobile test strip for use in environmental monitoring and health research worldwide.