The Economic Survey of India, 2024-25, estimates the country’s real GDP (gross domestic product) growth for FY2025-26 to be in the range of 6.3-6.8%, which is much lower than last year’s Provisional Estimate growth of 8.2%. The jury is still out on whether this represents a structural decline or a blip – the growth expectation for the next year may decline further now due to ongoing trade wars and the spectre of a global slowdown.

A country’s capital formation level is a good yardstick for assessing its structural growth. According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), India has invested 30-32% of its GDP (gross capital formation in current prices) over the last few years. An incremental capital-output ratio (additional capital needed to produce one more unit of output) of 4.5 for India (Mohan 2019), will yield a trend GDP growth rate of 6.5-7% per year. Increasing structural growth to an annual rate of over 8%, which is consistent with the Viksit Bharat@2047 aspiration, requires a higher investment rate of 35% or more. Why is the Indian economy not investing more?

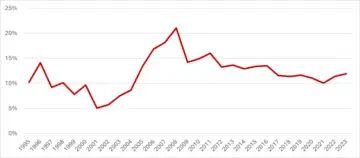

Capital formation trends are primarily driven by the capital expenditure (CapEx) cycle of the private corporate sector, the revival of which has remained elusive for some time now. During India’s surge growth years of 2004-2008, when the corporate investment ratio reached its peak, corporates invested an average of 16% of GDP, compared to 12% in FY2022-23, and it has been subdued for some time (Gupta and Sachdeva 2022).

Figure 1. Private corporate gross capital formation to GDP ratio (current prices)

Source: Corporate investment and GDP data are from National Accounts Statistics at current prices, 2011-12 series.

Why is ‘India Inc.’ not investing?

This begs the question – why are corporates not investing as much, especially when their profitability is back and banks are also in a position to lend, given that their balance sheets are much healthier now?

Corporate profitability, measured as net profit after tax to sales ratio, is at 7% in 2023, almost double what it had been for a decade and close to what it was during 2004-2008. Similarly, the banks’ gross non-performing assets as a share of gross advances have declined to 2.6%, compared to an average of 6% during the second half of the previous decade (Reserve Bank of India, 2024). Corporate investment is a function of corporate profitability and growth outlook. The former represents their ability to invest, and the latter, willingness (Gupta and Sachdeva 2022). While profitability is back, the growth outlook remains tepid. During 2004-2008, the following year’s growth outlook for the Indian economy was around 8%; currently, it is around 6.5%. This moderate growth outlook dampens corporate animal spirits to push the pedal on creating capacity at a faster pace. Thus, India Inc. is not holding back on investment, as the general discourse makes us believe; their investment level is consistent with their assessment of demand growth for the future. Higher corporate investment necessitates a better growth outlook.

Figure 2. Corporates invest in accordance with their level of profitability and growth outlook

Sources: (i) The investment-sales ratio and profit-sales ratio are from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Prowess database. (ii) Growth projections are from various issues of the World Economic Outlook.

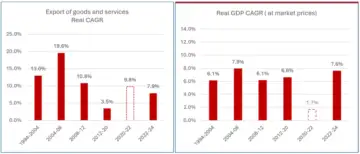

Growth outlook and exports

This raises another question: why is the growth outlook moderate now compared to the surge growth years? One key component that drives any economy’s growth is its export growth performance. The same is true for India. The country’s real export growth increased from 13% during 1994-2004 to close to 20% during 2004-2008 and fell to 3.5% during 2012-2020, before recovering somewhat in the last few years. GDP growth followed the same trend; it increased from 6.1% to 7.9% before falling to 6.6% across the respective periods. Given the ongoing fragmentation of the global economy, the outlook on global trade growth is not any better compared to the recent past. For India to have better growth prospects, its exports must grow significantly faster in this sluggish global trade environment. This can only happen if India becomes more competitive in the global market so that it can negate the decelerating effect of the fracturing global economy. How do we achieve better export growth?

Figure 3. India’s real export and GDP growth rate

Note: The years mentioned are financial years, calculated at 2011-12 prices. 2020-22 refers to the Covid-19 pandemic period and hence is an anomaly. Source: National Account Statistics.

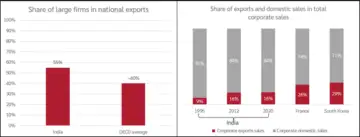

The role of large firms in exports

In most countries, large firms are the primary vehicle of exports; India is no different. About 55% of India’s exports are accounted for by large firms ; this share being 40-45% for the OECD countries (OECD, 2024). However, close to 85% of Indian firms’ revenues come from the domestic market; this share being 70% for countries like South Korea (Abe and Kawakami 1997) and 74% for France (Berman 2015). Since international markets provide unlimited potential for Indian firms, this skew towards the domestic market has to be due to their inability to compete more deeply in the global markets.

Figure 4. Higher exports require large firms selling more to global markets

Notes: (i) Corporates refer to large companies as mentioned in CMIE Prowess. The database is built from the audited Annual Reports of companies and information submitted to the Ministry of Company Affairs; and in the case of listed companies, the database also includes company filings with stock exchanges and prices of securities listed on the major stock exchanges. (ii) In 2001, exports of large firms in France with more than 500 employees accounted for 26% of their total sales (Berman 2015). In 1993, in South Korea, for firms with 200-299 employees, 29% of their sales were in the form of exports (Abe and Kawakami 1997). Source: National Accounts Statistics, CMIE Prowess, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2024).

It is well understood that Indian firms operate in a tough regulatory environment: tedious labour laws requiring firms with more than 100 employees to obtain prior government permission before retrenching workers, a real interest rate that is on average 2% higher than in China (World Bank) since 2010, expensive land – the price-to-income (PTI) ratio of housing in urban India is 11 relative to the affordability benchmark of 5 – among others (Gupta, Agnihotri and George 2023). These impediments raise the cost of production, making Indian products less competitive. That is why there is a universal acceptance that factor markets – labour, capital, and land – must be reformed for GDP growth acceleration by making Indian companies more competitive. The Finance Minister, in her recent Union Budget speech, emphasised, “The government will establish a comprehensive Economic Policy Framework to guide the nation’s development, focusing on increasing productivity and market efficiency. The framework will address all factors of production, including land, labour, capital, and entrepreneurship, with technology playing a critical role in improving total factor productivity and reducing inequality.” (Government of India, 2025)

Unleashing land reforms is a must

Amongst factor markets, we believe equal priority (if not more) must be given to reforming the land market, as is usually given to labour. Firms resort to contractualisation as a way out of onerous labour laws and move to the hinterland and have multi-plants to avoid expensive/unavailable land in big cities (Anand et al. 2024). While the former leads to a lack of a long-term relationship between the firms and the workers, the latter results in a dispersed growth model that compromises on creating world-class agglomerations that have powered growth for countries like China. For example, according to a 2009 McKinsey Report, concentrated growth models would produce up to 20% higher per capita GDP than more dispersed growth scenarios in China (McKinsey & Company, 2009). This is reflected in the GDP and the population of the biggest cities across the two countries. While Mumbai and Delhi have a population of around 25-30 million, slightly more than the population of between 20-25 million for Beijing and Shanghai, the former has a GDP in the range of US$100-150 billion (Government of Maharashtra, 2023), compared to US$500-550 billion for their Chinese counterparts (National Bureau of Statistics of China).

The government can make land affordable by releasing (developable) land supply transparently through credible and rigorous land use and implementation. This will increase the supply of land and competition in the sector by enabling and encouraging the entry of new real estate developers, putting pressure on prices, and in turn, improving affordability. Since the government is also one of the biggest landowners, it can lead by example in terms of reforming the sector. A transparent market not just enables economic growth by making land affordable, it is also good for development and employment. Affordable land will reduce PTI, enabling people to live in decent housing, a must for a dignified living. This process will boost GDP growth and create much-needed non-farm employment. In conclusion, higher investment hinges on unleashing the next generation of land reforms.

Shishir Gupta is a Senior Fellow at CSEP in New Delhi. His work focuses on many aspects of the Indian economy, including economic growth, governance and institutions, urbanisation, and sub-national reforms, among others.

Rishita Sachdeva is an Associate Fellow with the Economic Growth and Development vertical. She has an MSc Development Economics from University of Sussex. Previously, she has interned with UNDP and NITI Aayog. She is currently working on India’s economic growth project. She is interested in development economics and politics.

The analysis is derived from the authors’ working paper – India’s New Growth Recipe: Globally Competitive Large Firms (2022).

This article was first published on Ideas for India.