In 2025, the Supreme Court of India did not wait to be approached. Many a time, it noticed something amiss – a newspaper report, a troubling order, a systemic failure – and stepped in on its own motion.

Seventeen times over the year, the Court invoked its extraordinary suo motu jurisdiction.

Read together, these cases form a map of where governance failed, where institutions faltered and where even High courts needed correction.

What follows is a thematic account of some of the most important such interventions.

Lokpal vs Judiciary: Who watches the watcher?

Lokpal, Supreme CourtThe year opened with the Supreme Court confronting a question of Constitutional importance.

Lokpal, Supreme CourtThe year opened with the Supreme Court confronting a question of Constitutional importance.

In February 2025, the Court took suo motu cognisance of an order passed by the Lokpal which had directed a preliminary inquiry against a sitting High Court judge.

The concern was not about shielding judges from scrutiny. It was about jurisdiction. Could a statutory body created by parliament exercise oversight over constitutional courts without violating judicial independence?

A Bench led by then Chief Justice of India (CJI) BR Gavai noted that judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court are governed by distinct accountability mechanisms, including impeachment under Articles 124 and 217 of the Constitution. Allowing an external statutory authority to conduct inquiries, even at a preliminary stage, could have a chilling effect on judicial independence, the apex court opined.

It stayed the Lokpal’s directions, while indicating that the issue raised serious constitutional questions requiring authoritative determination.

As things stand, the matter remains pending before the top court. But even at this interim stage, the Court’s suo motu intervention performed a crucial function. It froze a potentially far-reaching precedent before it could harden into practice.

This case set the tone for the year. The Supreme Court was not merely reacting to governance failures outside. It was also policing the edges of its own constitutional ecosystem, ensuring that accountability does not come at the cost of independence.

When the Court arrived after the trees were gone

Supreme Court of India, TreesThe Supreme Court’s second suo motu intervention of 2025 reflected a familiar judicial frustration in environmental cases, since by the time the Court was alerted, the damage was already done and irreversible.

Supreme Court of India, TreesThe Supreme Court’s second suo motu intervention of 2025 reflected a familiar judicial frustration in environmental cases, since by the time the Court was alerted, the damage was already done and irreversible.

The matter concerned large-scale tree felling in the Kancha Gachibowli forest area near Hyderabad, a region that had increasingly come under pressure due to rapid urban expansion and proximity to the city’s IT corridor. What was projected as “development activity” was, on the ground, the near-complete clearing of a forested tract that had long functioned as a green buffer.

The Court took notice of the matter arose from media reports and public disclosures. It to examine whether statutory safeguards under environmental and forest laws had been reduced to mere formalities. It asked the State of Telangana to show how clearances were issued, whether due process under environmental laws was followed and why precautionary principles appeared to have been sidelined.

Following the Court’s intervention, the State halted the tree-felling activity. The exercise was put on hold pending further directions of the Court. What had until then been proceeding as an administrative fait accompli was suddenly frozen, not because of a stay petition or an interim injunction sought by a litigant, but because the Court itself chose to step in.

The proceedings exposed a structural weakness – environmental decision-making is often fragmented across departments, allowing responsibility to be diffused when things go wrong. By taking suo motu cognisance, the Supreme Court attempted to re-centralise accountability – even if belatedly.

Stray dogs and a city on edge

Supreme Court, Stray DogThe Supreme Court’s suo motu intervention in the stray dogs issue in 2025 did not begin in a courtroom. It began with a newspaper report.

Supreme Court, Stray DogThe Supreme Court’s suo motu intervention in the stray dogs issue in 2025 did not begin in a courtroom. It began with a newspaper report.

The report spoke of a disturbing rise in stray dog bite incidents, particularly involving children. It highlighted deaths, grievous injuries and what was described as municipal paralysis – animal birth control programmes that existed merely on paper, overcrowded shelters and local authorities unsure of what they were legally permitted to do.

Taking of the report, Justice JB Pardiwala registered proceedings to examine what he saw as a breakdown of basic urban governance.

From the very first hearing, Justice Pardiwala’s concern was unambiguous. He repeatedly flagged that while animal welfare laws and the Animal Birth Control Rules were being cited endlessly, human safety, especially the safety of children, appeared to have been relegated to the background.

Justice Pardiwala’s observations were sharp and, at times, deliberately unsettling. He questioned whether governance had reached a stage where authorities were “more afraid of contempt than of dead children.” The Court’s initial directions reflected that urgency.

That urgency translated into sweeping directions. Justice Pardiwala ordered the Delhi government, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi and the New Delhi Municipal Corporation to begin removing stray dogs from all localities in Delhi, with particular focus on vulnerable areas. It said there should be no compromise in the exercise and directed authorities to make every locality free of stray dogs, leaving it to the administration to decide the operational mechanism, including the creation of a dedicated force if necessary.

The Court warned that any individual or organisation obstructing the rounding up or removal of stray dogs would face strict action, including contempt of court.

These directions, however, triggered intense backlash.

Animal rights groups, activists and several civil society organisations protested what they perceived as a judicial endorsement of mass removal or displacement of stray dogs. There were public demonstrations, petitions and open letters criticising the tone and tenor of the proceedings.

The controversy was no longer limited to dogs. It had become a debate on judicial limits, empathy and the optics of constitutional adjudication.

At this stage, a significant institutional decision was taken. The matter was placed before a new Bench led by Justice Vikram Nath. What followed was not a repudiation of the earlier concerns, but a course correction.

Justice Nath’s Bench the focus of the case. The Court clarified that it was not endorsing indiscriminate removal or killing of stray dogs. It emphasised that the governing framework remained the Animal Birth Control Rules, which mandate sterilisation, vaccination and humane treatment.

One of the first corrective steps taken by the Bench was to direct that stray dogs that had been removed pursuant to earlier directions be released, subject to compliance with vaccination and sterilisation norms. The Court made it clear that public safety and animal welfare were not mutually exclusive objectives.

Crucially, the scope of the proceedings began to expand. The Court recognised that stray dogs were only one symptom of a larger urban management failure. It began examining issues relating to stray cattle, unauthorised feeding in public spaces, lack of fencing around highways and sensitive zones and the complete absence of coordinated urban animal management policies.

As the case stands today, it remains pending and evolving. The Supreme Court continues to monitor compliance, calling for data, action plans and timelines rather than issuing sweeping prohibitions. The emphasis is now on implementation, not ideology.

Jojari pollution: A dying river, a familiar story

River Polluted with Industrial WasteThe Supreme Court’s in the Jojari river pollution case was triggered, once again, by reports and materials placed before the Court showing the steady, visible death of a river in Rajasthan.

River Polluted with Industrial WasteThe Supreme Court’s in the Jojari river pollution case was triggered, once again, by reports and materials placed before the Court showing the steady, visible death of a river in Rajasthan.

The Jojari River, which flows through parts of western Rajasthan and eventually joins the Luni river, had for years carried untreated industrial effluents, sewage and chemical waste. What brought the issue to a head in 2025 was the scale and normalisation of the pollution. The river was no longer polluted in patches. It had effectively become a flowing drain, with direct consequences for agriculture, groundwater and public health.

A Bench led by Justice Nath once again noted that Rajasthan’s latest report, filed in November 2025, showed “remedial action only after the Court intervened.” It recorded that inspection drives had been intensified, but said such efforts came “years too late.”

The Court disapproved of the State’s belated action and said that the measures undertaken, though welcome, must be viewed as the beginning of a process rather than an adequate response.

It then constituted a High-Level Ecosystem Oversight Committee headed by former Rajasthan High Court Justice Sangeet Lodha to supervise river restoration efforts.

The message was unmistakable – environmental degradation would no longer be addressed through symbolic notices or paper compliance. If regulators failed to regulate, the Court would step in, stay engaged and demand answers.

Summoning lawyers: Drawing the line for investigating agencies (read ED)

Supreme Court, EDThe Supreme Court’s suo motu intervention on the summoning of advocates by investigating agencies was not triggered by a judgment, a protest, or even a newspaper report. It was triggered by something more rarer – outrage from the Bar.

Supreme Court, EDThe Supreme Court’s suo motu intervention on the summoning of advocates by investigating agencies was not triggered by a judgment, a protest, or even a newspaper report. It was triggered by something more rarer – outrage from the Bar.

In early July 2025, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) issued summons to Senior Advocates Arvind Datar and Pratap Venugopal. Datar had rendered a legal opinion in a money laundering case and Venugopal was the advocate-on-record. Neither was accused of laundering money. Neither was alleged to have benefited personally. Their connection to the case was professional.

What followed was swift and sharp backlash. Bar bodies across the country called it an existential threat to the legal profession.

The Supreme Court did not wait for a petition.

Taking suo motu cognisance, a Bench headed by then CJI BR Gavai along with Justices K Vinod Chandran and NV Anjaria, framed the issue in institutional terms – can an investigating agency summon a lawyer simply for doing their job?

Before the Court could even hear the matter at length, the ED withdrew the summons. But the damage, the Court felt, had already been done.

In a detailed judgment, it held that as a rule, investigating agencies cannot summon lawyers in connection with advice given to clients or representation provided in court. Doing so, the Court said, strikes at the heart of attorney-client privilege, now statutorily recognised under Section 132 of the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023.

The Bench made three things unmistakably clear. First, privilege is not a “perk” of lawyers. It is a structural necessity for the justice system. Without it, clients will not speak freely, and lawyers cannot advise fearlessly.

Second, the law already contains narrow exceptions, where the communication itself furthers an illegal purpose, or where the lawyer is not acting merely as a lawyer. But these exceptions cannot be invoked casually or tactically.

Third, even in exceptional cases, procedural safeguards are mandatory.

Digital arrest scams: When fraudsters wore judicial robes

Cyber crimeThe Court’s on digital arrest scams was triggered by something far more unsettling than financial fraud. It was triggered by the forgery of the Court itself.

Cyber crimeThe Court’s on digital arrest scams was triggered by something far more unsettling than financial fraud. It was triggered by the forgery of the Court itself.

The immediate spark was a letter received by the Supreme Court from a senior citizen couple, who said they had been defrauded of their life savings after being virtually “arrested” by people impersonating officials of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), the ED and even the judiciary. The fraudsters conducted video calls, issued threats of arrest and, most alarmingly, displayed forged Supreme Court orders carrying fake judicial signatures and official-looking seals.

The amounts involved were staggering. In that one case alone, the couple said they were coerced into transferring around ₹1.5 crore over multiple transactions. Media reports suggested this was not an isolated episode, but part of a wider pattern targeting elderly citizens across States.

Taking suo motu cognisance, a Bench of CJI Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi registered proceedings to examine what it described as a grave, organised cybercrime phenomenon.

Recognising the scale and inter-State nature of the offence, the Court to take over the investigation, observing that such crimes could not be effectively addressed through fragmented State-level probes.

When judicial language did the damage

Allahabad HC, Supreme CourtThis intervention by the Supreme Court was triggered by something more unsettling – the way a court spoke about sexual violence involving a child.

Allahabad HC, Supreme CourtThis intervention by the Supreme Court was triggered by something more unsettling – the way a court spoke about sexual violence involving a child.

The episode began with a judgment of the Allahabad High Court modifying a trial court’s summoning order in a case involving an 11-year-old girl. The allegations were stark. The accused were accused of having grabbed the child’s breasts, broken the string of her pyjama and attempted to drag her beneath a culvert, before fleeing after passers-by intervened. The trial court found the accused guilty of rape and attempted penetrative sexual assault under the POCSO Act.

The High Court disagreed. It diluted the charges, holding that the acts alleged did not show a “determined intent” to commit rape and amounted only to preparation, not attempt.

What caused disquiet was not just the conclusion, but the language and reasoning, which appeared to dissect the incident in a manner many felt lacked sensitivity to the lived reality of sexual violence.

Although a Supreme Court Bench led by Justice Bela M Trivedi initially declined to entertain a PIL against the order, the matter resurfaced after being flagged by a civil society organisation. This time, the Court chose to act.

Taking suo motu cognisance, a Bench of Justices BR Gavai and AG Masih stayed the operation of the High Court’s order. The Court was unsparing in its assessment. It described parts of the High Court’s reasoning as reflecting a “total lack of sensitivity”.

The immediate impact was clear. The diluted charges were effectively restored for trial, the High Court’s observations were put in abeyance and the Supreme Court signalled that judicial language in sexual violence cases is not a matter of style, but of constitutional responsibility.

The matter remains pending for broader consideration with the possibility of authoritative guidance on the issue.

Judge under attack

Justice Moushumi BhattacharyyaThe spark for this intervention was a transfer petition filed before the Supreme Court, seeking to move a case out of the Telangana High Court. The underlying dispute related to criminal proceedings against Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy, which had been quashed by a Bench of the High Court presided by Justice Moushumi Bhattacharya.

Justice Moushumi BhattacharyyaThe spark for this intervention was a transfer petition filed before the Supreme Court, seeking to move a case out of the Telangana High Court. The underlying dispute related to criminal proceedings against Telangana Chief Minister A Revanth Reddy, which had been quashed by a Bench of the High Court presided by Justice Moushumi Bhattacharya.

On paper, it was an ordinary transfer plea. In substance, it was not.

While seeking transfer, the litigant made serious and unsubstantiated allegations against Justice Bhattacharya. The petition suggested a “likelihood of derailment of justice” and questioned the impartiality of the judge. It also alleged that counsel was given only five minutes to argue the matter.

When the petition came up before the Supreme Court, a Bench of CJI BR Gavai and Justice K Vinod Chandran immediately flagged the language used by the litigant. The Court was not dealing with sharp criticism or robust disagreement. It was dealing with what it called “scurrilous and scandalous allegations” against a sitting High Court judge.

Suo motu were issued not only to the litigant, but also to his lawyers. In a subsequent hearing, the Supreme Court directed the litigant and his lawyers to tender apologies directly before Justice Moushumi Bhattacharya. The Court made it clear that it would be for the judge concerned to decide whether the apology was acceptable.

Justice Bhattacharya eventually accepted the apologies, though not without recording her disagreement with the allegations made against her.

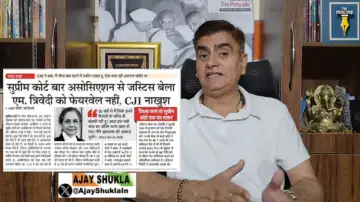

Ajay Shukla and the limits of criticism

Ajay ShuklaThe Ajay Shukla suo motu contempt case was about what happens outside the courtroom, in the age of YouTube, social media and thumbnails.

Ajay ShuklaThe Ajay Shukla suo motu contempt case was about what happens outside the courtroom, in the age of YouTube, social media and thumbnails.

The Supreme Court issued a suo motu criminal contempt notice against Shukla, a Chandigarh-based journalist, over a video published on his YouTube channel around the retirement of Justice Bela M Trivedi. The video’s caption referred to the judge as a “Godi judge”, a politically loaded term commonly used to suggest institutional alignment with the BJP-led Central government.

The Bench noted that the video contained scandalous observations against one of its senior judges and that such content, when widely published on YouTube, was likely to bring disrepute to the judiciary.

The Court did not say that judges are immune from criticism. It said that defamatory and scandalous allegations, particularly when amplified on digital platforms, cross a constitutional line.

Notably, this was the only suo motu criminal contempt initiated by the Supreme Court in 2025. That choice signals restraint as much as resolve. The Court did not launch a broad crackdown on media criticism. It acted in one case where it believed the threshold of scandalisation had clearly been crossed.

When the Court stayed back for the environment

HillsDuring the winter break of 2025, the Supreme Court its own recent ruling on the Aravalli Hills after acknowledging that the definitions it approved last month require further clarification amid widespread environmental concerns.

HillsDuring the winter break of 2025, the Supreme Court its own recent ruling on the Aravalli Hills after acknowledging that the definitions it approved last month require further clarification amid widespread environmental concerns.

A Bench of CJI Surya Kant and Justices JK Maheshwari and AG Masih stayed the November 20 judgment delivered by former CJI BR Gavai that had accepted an elevation-linked definition of the Aravallis for mining regulation.

The Court said that an independent expert committee, distinct from the earlier panel dominated by bureaucrats, would be constituted to assess the environmental impact of the newly approved definitions. While noting that there was no scientific material on record to justify immediate interference, the Court recognised a “significant outcry among environmentalists” and held that the backlash appeared to stem from ambiguity in the Court’s own directions.

Until the expert review is completed, both the earlier judgment and the committee’s recommendations will remain in abeyance.

The Aravalli pause was not the only environmental alarm the Supreme Court responded to during the winter break. A separate vacation bench also took suo motu cognisance of large-scale encroachment and illegal grabbing of forest land in Uttarakhand.

It ordered an on all construction activity on forest land, barred the creation of third-party rights and directed the Forest Department to take possession of all vacant forest land, excluding areas already occupied by residential houses.

Taken together, these suo motu interventions tell a coherent story. They mark a year in which the Supreme Court repeatedly stepped into spaces left vacant by executive inertia, regulatory fatigue and institutional drift.

Suo motu power, often criticised as exceptional or intrusive, became in 2025 a tool of last resort, used not to govern, but to remind those entrusted with governance of their obligations.

Whether that reminder translated into lasting reform is a question the coming years will answer.