New Delhi: On Independence Day 2003, the then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, declared from the ramparts of the Red Fort, “Our country is now ready to fly high in the field of science. I am pleased to announce that India will send her own spacecraft to the moon by 2008. It is being named Chandrayaan I.” The ISRO scientists came up with an orbiter mission, but the former President APJ Abdul Kalam insisted on packing in the Moon Impact Probe, so that India could reach the lunar surface. The Chandrayaan 1 mission launched on 22 October 2008, and the Moon Impact Probe reached the lunar surface on 14 November 2008, almost exactly at the Lunar South Pole.

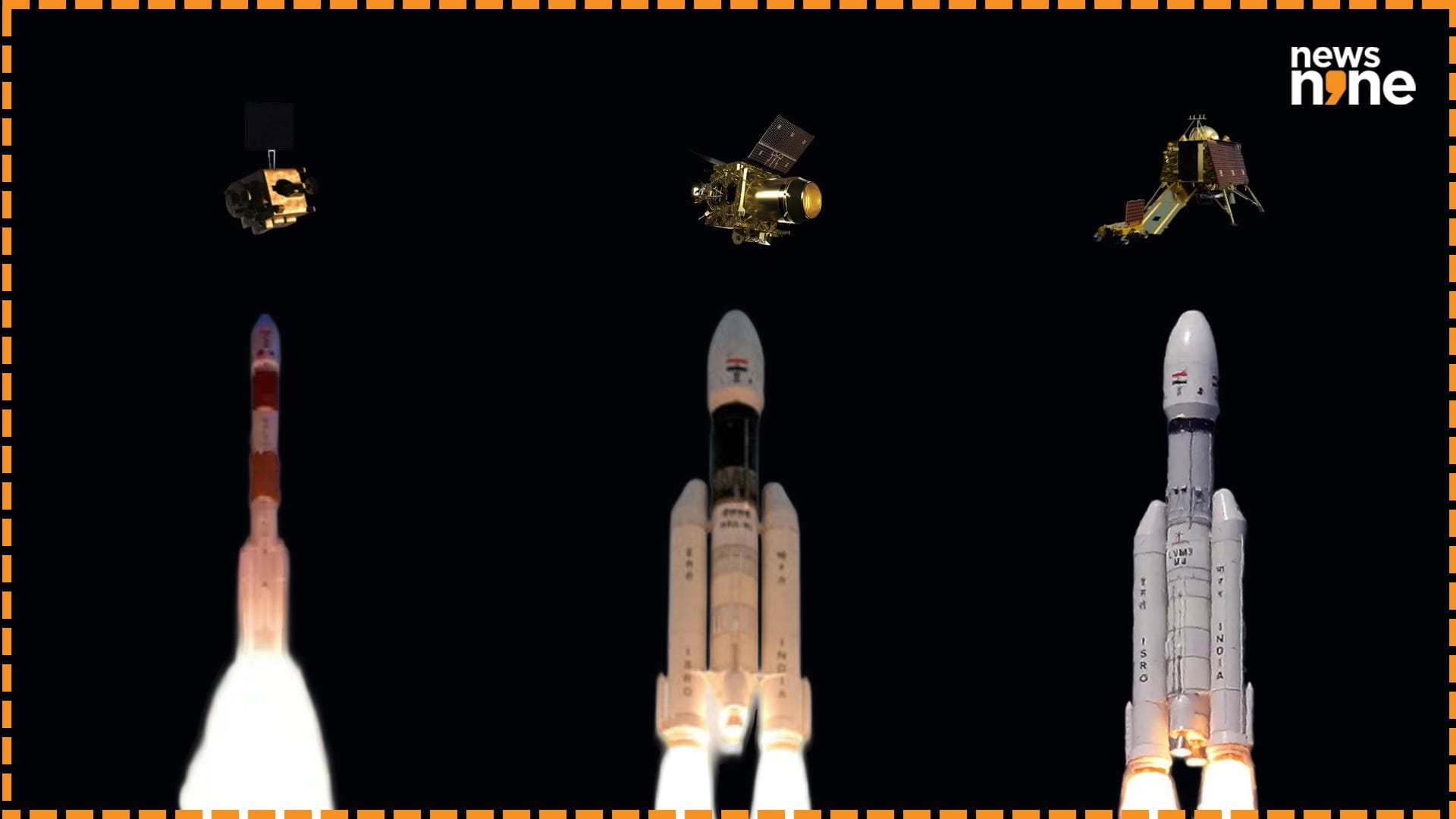

Liftoff of the PSLV-C11/ Chandrayaan-1 mission. (Image Credit: ISRO).

On board the Moon Impact Probe was the Moon Minerology Mapper payload from NASA that confirmed the presence of water on the surface of the Moon. In 1961 itself the American Theoretical physicist Kenneth Watson suggested that water ice delivered to the Moon in the chaotic infancy of the Solar System by asteroids would have remained in the permanently shadowed craters in the highlands around the lunar south pole. NASA’s Clementine spacecraft discovered strong hydrogen concentrations at the lunar south pole in 1994, leading the US Defence Department and NASA to declare that they had discovered ice on the Moon. The Chandrayaan 1 mission confirmed the presence of ice in the region.

Humanity’s return to the Moon

The discovery of water ice on the Moon renewed interest in Lunar missions. Now, all the major spacefaring nations in the world have plans of landing humans at the lunar south pole, and building a lunar base in the region. In 2003, India was depending on foreign launchers to deploy its INSAT series of satellites, and there was a requirement for a more powerful indigenous rocket. The GSLV was being developed, along with India’s own cryogenic engine. For the developmental flights of the GSLV, ISRO used cryogenic upper stages supplied by Russia.

ISRO Mission Control Centre when Vikram crashed. (Image Credit: ISRO).

For its return to the Moon, India initially collaborated with Russia. Chandrayaan 2 was envisioned as a joint mission with Russia, with ROSCOSMOS realising the lander and ISRO realising the rover. However, the plans were changed following the failure of the Phobos-Grunt sample return mission to one of the two moons of Mars in 2011. UR Rao oversaw an integrated programmatic review of India’s lunar exploration programme, and recommended that India use its own lander. This lander crashed into the Moon on 6 September 2019.

Chandrayaan 3 on the lunar surface with the payloads deployed. (Image Credit: ISRO).

ISRO studied the failure and realised that a number of factors had to line up perfectly for the soft landing. Over a hundred changes were made to the design of the spacecraft, under a new ‘failure-based design’ approach where the landing would be successful even if a number of components failed and off-nominal situations developed. Instead of five retrothrusters, the lander used a more stable configuration of four. The legs of the lander were fortified to accommodate a greater horizontal velocity at touchdown. On 23 August 2023, the Chandrayaan 3 lander successfully executed a soft landing on the lunar surface, demonstrating India’s capabilities of delivering a payload of its choice at the time and place of its choosing, on the Moon.

The Road Ahead

India has planned a comprehensive roadmap for lunar exploration. The Chandrayaan 4 mission is an ambitious sample return mission, which will see ISRO drilling and scooping up samples from the lunar surface and returning it to the Earth for further analysis. The Chandrayaan 5/LUPEX mission is a collaboration between ISRO and JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, where India will provide the lander, and Japan will provide a rover and the launch vehicle. ISRO is aiming to launch the Chandrayaan 4 mission in 2027 and the Chandrayaan 5 mission in 2028.

Illustration of the LUPEX rover on the Chandrayaan 5 mission. (Image Credit: JAXA).

ISRO is also planning the Chandrayaan 6 and 7 missions between 2030 and 2035, to demonstrate in-situ resource utilisation, or 3D printing using the locally sourced lunar regolith as ink, and a nuclear heat source for sustaining operations on the lunar surface beyond a single lunar day. This will be followed up by two flights to demonstrate a human-rated lander, followed by a mission to land an Indian on the lunar surface by 2040. ISRO then plans to expand its activities on the lunar surface, by building a cislunar orbital platform, called the Bharatiya Chandra Dwar, as well as a lunar surface research base called the Bharatiya Chandra Niwas. ISRO is also planning to develop a Moon buggy or a lunar terrain vehicle, as well as build a power plant on the lunar surface.