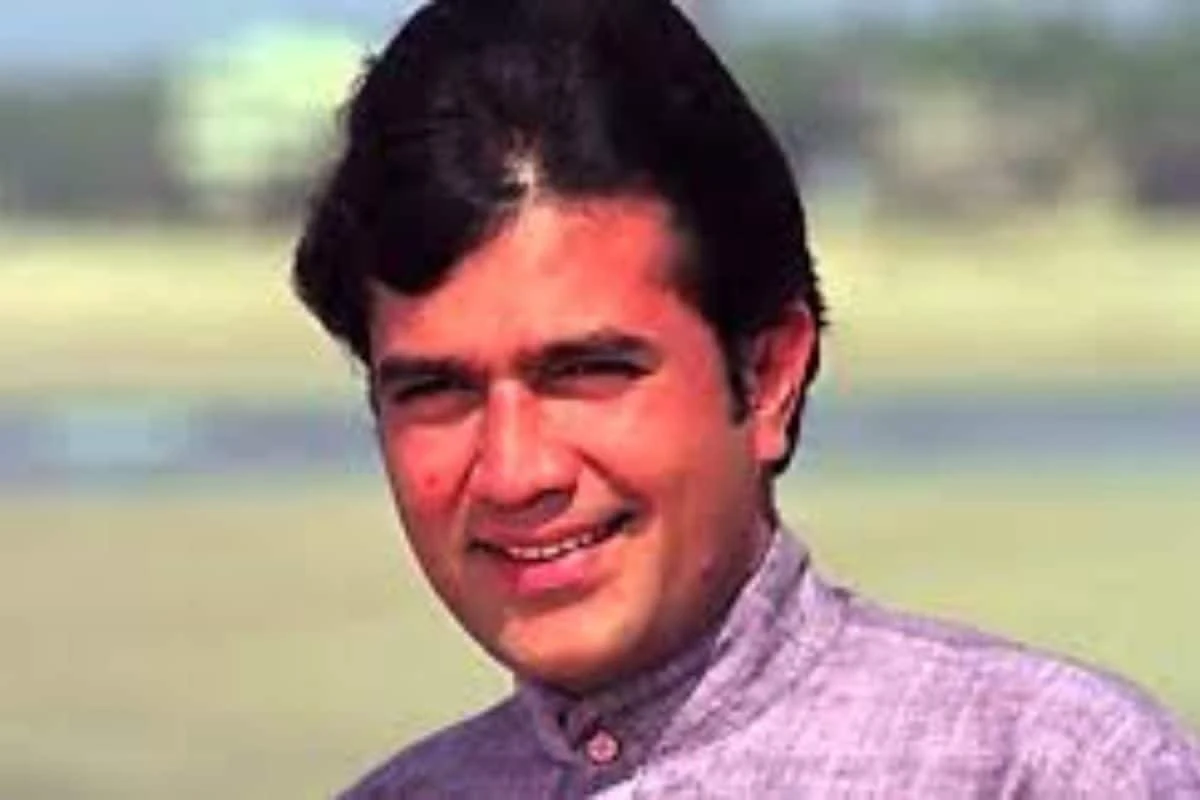

There was a time when Rajesh Khanna was more than a star, he was a phenomenon. His fans would line up outside theatres, write letters by the thousands, and even name children after him.

For a brief period in the early 1970s, he had a magical run where almost every film he touched became a hit, turning him into the undisputed “first superstar” of Indian cinema. But stardom, as luminous as it is, doesn’t last forever, and for Khanna, the fall from that pedestal was as dramatic as his rise.

The superstar era began to shift in 1973 when Amitabh Bachchan emerged with Zanjeer. Both Khanna and Bachchan starred in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Namak Haraam that year, a film that subtly signaled a changing of the guard. While Khanna continued to have hits like Aap Ki Kasam and Roti, the golden streak of consecutive successes that once defined him was over. By 1975, with Bachchan’s Sholay and Deewaar dominating the box office, Khanna’s films struggled to make a mark, and the once untouchable superstar began to face public scrutiny.

Friends and collaborators noticed the change early on. Sharmila Tagore once said, “Kaka either couldn’t or didn’t reinvent himself to remain contemporary, so much so that he became almost a caricature of himself and people began to mock him.” Directors who had once relied on his charm found his unpredictability and off-screen habits, including late-night drinking binges, increasingly difficult to manage. Even Yash Chopra, who had started his banner with Khanna’s support, felt he couldn’t accommodate the superstar tantrums anymore.

The 1980s proved to be especially harsh. Khanna’s personal life mirrored the struggles in his career. His marriage to Dimple Kapadia was on shaky ground, and with a string of flops, the actor’s confidence was low. Dimple described his state to India Today in 1985 as “pathetic,” recalling, “When a successful man goes to pieces, his frustration engulfs the entire surroundings. It was a pathetic sight when Rajesh waited at the end of the week for collection figures but the people didn’t have the guts to come and tell him.”

Then came Avtaar in 1983, a film that gave him a brief revival. Playing an elderly man dealing with grown-up children, Khanna surprised both critics and audiences. To shoot the bhajan “Chalo Bulava Aaya Hai,” he even walked to the Vaishno Devi temple on foot and shared the crew’s basic facilities like sleeping on the floor, something Shabana Azmi remembered vividly. “At that point in time, Rajesh Khanna couldn’t be like ‘I am a superstar,'” she said. Avtaar wasn’t a blockbuster like Coolie or Andha Kanoon, but for Khanna, it was a reminder that he could still connect with audiences.

Shabana Azmi, who co-starred with him, shared a memorable anecdote during a conversation with Radio Nasha. She recalled that there were no proper toilets on the shoot location-only public restrooms. Even Rajesh Khanna, a superstar accustomed to being pampered by his producers, had to wait in line holding a dabba. “At that point in time, Rajesh Khanna couldn’t be like ‘I am a superstar’,” she remarked.

Yet, old habits die hard. Khanna’s marriage with Dimple ended during the filming of Souten in 1982, and he later found solace in a relationship with Tina Munim. He openly admitted in Yasser Usman’s book, Rajesh Khanna: The Untold Story of India’s First Superstar, “I know over the past few years the lean patch in my career was attributed to my bad acting or bad habits. I was often advised to change. But I did nothing like that. What has actually changed is that over the last year I have been happy in my personal life. That is why I am not irritated any more. It has nothing to do with my films.”

Khanna attempted to explore new avenues, including film production and politics, but these ventures yielded mixed results. His production projects, though backed by stars like Tina Munim and supported by music legends RD Burman and Kishore Kumar, failed to recreate his cinematic magic. His short-lived political career offered the thrills of public adulation but little long-term success. Even his television efforts, such as Aa Ab Laut Chalein, did not capture the audience in the way his films once had.

By the later years, the superstar image had faded. Colleagues like Sachin Pilgaonkar noted, “Our industry functions on image. If the image is bad, it is very difficult to change it. Rajesh Khanna, towards the later phase tried to change, but perhaps it was too late. Unka naam kharab ho gaya tha (His reputation was ruined).” Attempts to stay relevant, such as appearing in films like Wafaa, often backfired and were perceived as desperate rather than innovative.

Rajesh Khanna passed away at the age of 69 in 2012. He spent a few years at the peak of his fame, basking in adoration, and then spent the rest of his life chasing that glory in different forms.