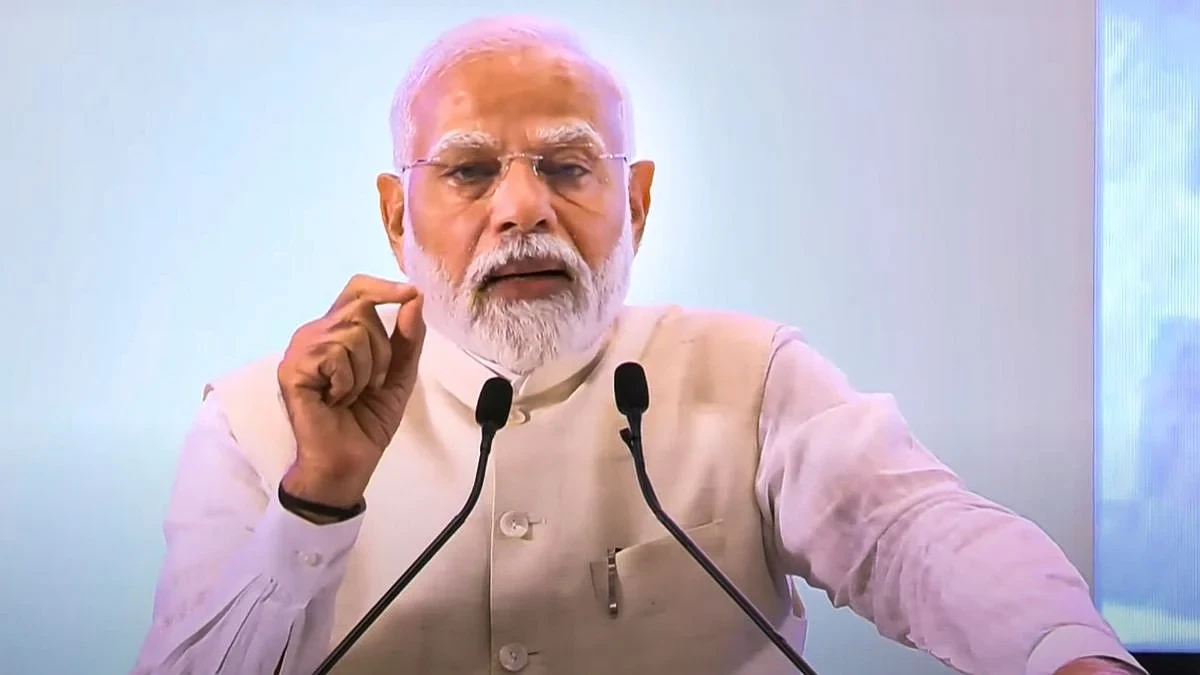

On Independence Day this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi stood at the Red Fort and offered Indians a different kind of freedom pledge: liberation from the country’s notoriously tangled tax code.

However, the question which haunts most Indians, businessmen and consumers alike, is, will this ambitious plan to slash rates for India’s GST tax really bring about a truly “Good and Simple Tax”?

At the same time, more serious analysts are asking aloud, ‘Did the government choose a year when the global trade architecture is already being redrawn under the assault of Trump tariffs to rework its own goods tax regime, as it intends to come up with sharper import duty give-aways than previously announced and wants to lower taxes for domestic players in anticipation?’

Modi’s announcement, framed as a “Diwali gift” to households, small entrepreneurs and microenterprises, is, on paper, the most ambitious restructuring of India’s Goods and Services Tax since its introduction in 2017.

Come October, if the rollout proceeds as planned, five separate tax slabs will collapse into a seemingly simpler two-tier system-5 per cent and 18 per cent-with a punitive 40 per cent reserved for alcohol, tobacco and other so-called “sin goods”.

The government’s pitch is straightforward: fewer rates, less paperwork, cheaper goods, faster growth.

The timing is deft. With elections looming in several states and consumer demand sluggish, the reforms are calibrated to speak both to households struggling with inflation and to small businesses burdened by compliance.

However, beneath the celebratory framing lie risks that could test both India’s fiscal stability and the political capital the Prime Minister has staked on the bold plan.

Why Reform and Why Now?: For years, economists and businesses have complained that India’s GST is one of the most complex in the world. Five tax rates, a compensation cess, and a thicket of exemptions spawned endless disputes-was a chocolate-coated biscuit a luxury or a staple? Should a washing machine face the same rate as a toaster?

Litigation piled up, and companies restructured supply chains simply to navigate tax classifications.

By contrast, the two-rate structure promises clarity. Essentials like ghee, soap, processed foods and handicrafts will drop into the 5 per cent slab, easing household budgets and giving relief to artisans and small enterprises. Big-ticket items-refrigerators, cement, air conditioners-shift from the punitive 28 per cent rate to 18 per cent, lowering housing costs and nudging manufacturing.

For the Modi government, the gamble rests on a familiar economic bet: cut rates, spur consumption, broaden the base and wait for the Laffer curve effect, a theory which says with lower rates of taxes, government revenues will eventually go up.

With the end of the compensation cess (paid to states for agreeing to go along with the GST, which severely curbed their power to raise taxes), fiscal space has opened up just enough to attempt it. At the same time, by aligning the GST rates more closely with global norms, India hopes to shield its producers from the added pressure of new free trade deals, which are already bringing in cheaper imports.

With the lowering of import duties agreed upon in a free trade deal signed with Great Britain and two other bigger ones in the works with the United States and the European Union, duty protection for Indian manufacturers is likely to go down drastically.

In the case of the United States, according to news reports, India is prepared to cut its average tariff differential with the US by nearly 9 percentage points-bringing it down from 13 per cent to under 4 per cent. Under the circumstances a slashing of the GST with its input credit system is expected to help lower manufacturing costs for Indian firms.

However, reforms of this scale rarely come without unintended consequences.

For instance, by telegraphing steep tax cuts two months in advance, the government has invited an awkward pause in the market. Distributors are already delaying purchases in anticipation of October’s lower rates.

Consumer goods companies fear September could see inventories pile up while buyers wait for discounts. The government insists its anti-profiteering provisions will prevent market distortions, but global precedents-Malaysia’s troubled GST experiment among them-suggest enforcement is messy at best.

Even with cuts, India’s rates remain higher than those in Southeast Asia, where the GST and VAT levels hover in the single digits. That gap matters for industries exposed to tariff reductions under free trade pacts. A fridge taxed at 18 per cent may be cheaper than before but still costlier than one imported from Vietnam or Thailand, for instance.

The central government is betting that consumption will surge enough to make up for short-term revenue losses. However, states, already bracing for the disappearance of compensation transfers in December, could see a sharp fiscal stress.

Health and education budgets-politically sensitive and already stretched-may be the first to feel the squeeze, and this ahead of key state elections next year could see its own share of the political blame game.

At the same time, moving nearly 1,500 goods and services into new categories is a massive logistical lift. Small firms will have to reprogramme billing systems, update software, and train staff to be able to comply, and the chances of glitches and misinterpretation of rates could well go up exponentially.

For many, the promise of relief may well be offset by the pain of transition.

Politics of Festival Gifts: For the ruling coalition at the centre, the symbolism of a Diwali “bonanza” is not accidental. Cheaper basics can be expected to resonate with households squeezed by inflation. Reduced costs for cement and construction dovetail neatly with the government’s housing-for-all agenda. Relief for handicrafts and microbusinesses gives a nod to sectors long pleading for recognition.

However, expectations, once raised, are hard to manage. If consumers fail to feel an immediate difference-or if hoarding and profiteering blunt the impact-the celebratory narrative could sour.

States, meanwhile, may push back hard in GST Council negotiations, wary of being saddled with a revenue risk which could see them sink deeper in the red.

In substance, the reforms are bold and overdue. Simplification was the missing ingredient in making the GST the seamless “one nation, one tax” system it was meant to be.

Cutting rates is also a pragmatic response to both consumer unease and competitive pressures coming from abroad, which has already seen a decade of rising unemployment even as the GDP has gone up.

The Modi government’s challenge in all this lies in the execution of the plan outlined by the Prime Minister. If it can manage the transition smoothly, prevent market distortions, and keep states on board, the reforms could breathe new life into India’s consumption story. If not, the “Diwali gift” may be remembered less as a festive bounty and more as a high-stakes gamble that failed to deliver.