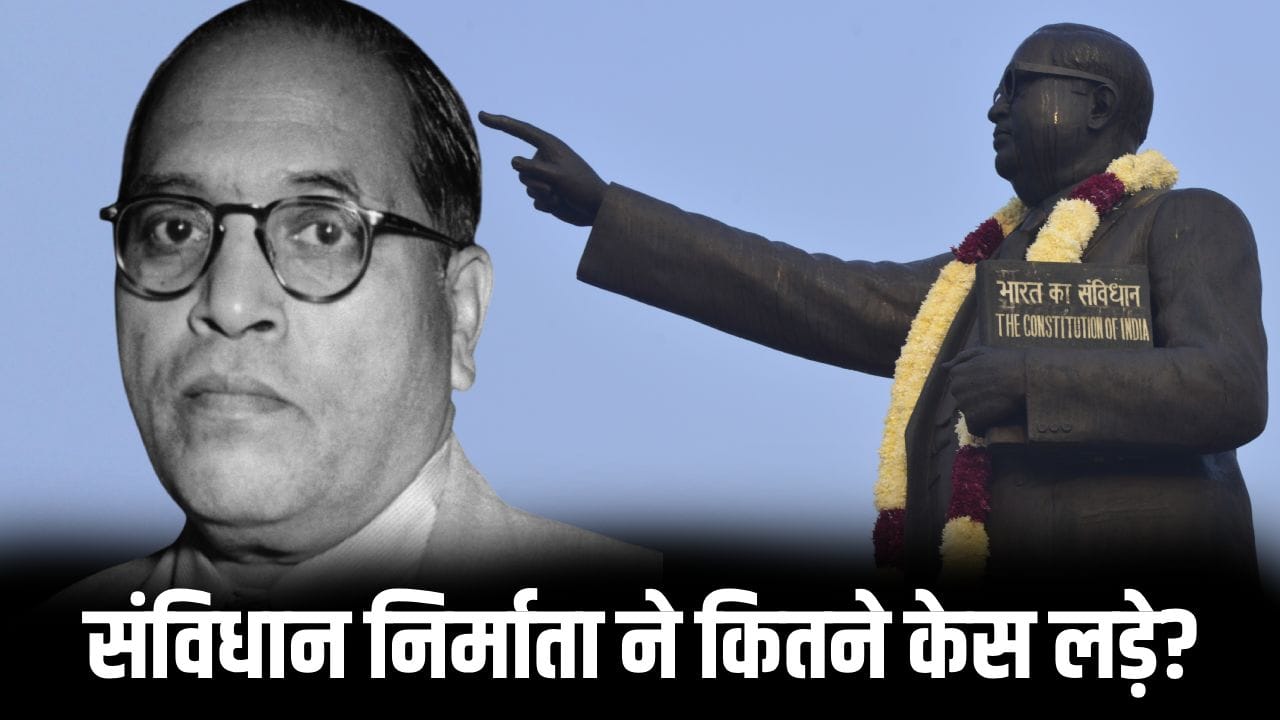

6th December is not just a date but a day of thought in the collective memory of India. This is the day when the nation remembers its great jurist, constitution maker and social revolutionary Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. Generally we see Dr. Ambedkar in the Constitution, Parliament and law books, but an important dimension of his life is also related to the cases fought in the courts. As a successful lawyer, flamboyant debater and astute jurist, Ambedkar not only argued in the courts but also challenged the very definition of justice.

Let us, on the pretext of his death anniversary (6 December), try to see what kind of cases Dr. Ambedkar fought, what was their nature, and how these cases shaped his thoughts and future politics.

From law school to courtroom

It is important to understand the background of Dr. Ambedkar’s judicial journey. He was not only a degreed lawyer, but also a serious scholar of jurisprudence. He did B.A from Bombay (Mumbai), M.A from Columbia University (USA). And did PhD. He managed to obtain a doctorate from the London School of Economics and also the degree of Barterlaw in the same London.

Such intensive legal education not only makes them professional lawyers, but also makes them thinkers who understand the soul of law. When he returned to India, he practiced mainly in the Bombay High Court. The scope of his cases was more related to socio-political and rights related questions than general criminal or civil disputes.

Dr. Ambedkar strongly criticized the British through his newspapers. Photo:Bettmann / Contributor/Getty Images

Cases related to Mahad Satyagraha, discrimination and rights

Dr. Ambedkar’s most important legal work was related to those cases in which questions were raised regarding the rights of the communities called untouchables. He was not just a lawyer in such matters, but a real leader and guide.

The Mahad Satyagraha of 1927 was a decisive event in Indian social history. Chavdar pond was a public water source in Mahad town of Konkan region, but Dalits were prohibited from taking water from there. Dr. Ambedkar not only led this movement politically, but when there was resistance, violence and cases were filed, he also fought this battle in the court.

The upper castes argued that the pond is not public, it is their property, and taking water from untouchables is against the law. Ambedkar presented two important arguments before the court. A- A water source built for a public purpose with public money cannot be the private property of any particular caste. Two- There is no valid provision in the Indian Penal Code and prevailing law which would deprive a person of water resources merely on the basis of caste based on birth.

The legal battle lasted a long time, but it set an important precedent that social movements would have to fight for legal recognition even within the courts.

Matters related to temple entry and religious places

The movement led by Ambedkar for entry into the famous Kalaram temple near Nashik also got embroiled in lawsuits. The question of temple entry was presented as a matter of religious autonomy versus a fundamental human right. Ambedkar underlined in his legal arguments that if the temple is run by public donations, public participation and state patronage, then keeping its doors closed to any one section is against the principle of equality of law.

These cases often got stuck in compromises, delays and technical objections, but Ambedkar forced the courts to think whether any institution or tradition has the right to humiliate a human being in the name of religious freedom?

Dr. Ambedkar repeatedly said that nothing will happen by changing the law books, Photo: Pankaj Nangia/ITG/Getty Images

Political rights lawsuits

Another major aspect of Dr. Ambedkar’s legal journey was related to the cases which focused on questions like representation, voting rights and separate constituencies. Although many of these struggles were fought in commissions, roundtables and constitutional debates rather than in formal trials, they were legal in nature.

Legal disputes related to agreements

In the Round Table Conference (London), Dr. Ambedkar demanded separate electorates for Dalits. The British government partially accepted it through the Communal Award, but Mahatma Gandhi went on a fast unto death in protest against it.

The result of this conflict was the Poona Pact (1932). Although it was legally a memorandum of understanding, many of its provisions later became references in debates on electoral laws and the Constitution.

Dr. Ambedkar basically defined this entire question in legal terminology. He raised the question whether historically disadvantaged groups have the right to be given separate political representation? Can the rights of minorities be protected without the constitutional morality of the majority class? He kept arguing on all these questions like a brilliant jurist.

Dr. Ambedkar was also an advocate of economic justice. In the early years of his practice in the Bombay High Court, he fought many cases involving contract disputes involving labourers, tenant farmers or small parties.

Matters relating to wages and conditions of industrial workers

After the Industrial Revolution, many lawsuits arose regarding working hours, minimum wages and working conditions for mill workers in Bombay city. Dr. Ambedkar often took the stand in these cases that it was unjust to consider only the contract as the final truth. The court has to look at the socio-economic circumstances in which the contract was entered into, and whether equality of the parties to the contract was actually present or not. This viewpoint later became the foundation of his pro-socialist and labor law reformist ideas.

Lawsuits related to press, expression and contempt

Dr. Ambedkar made sharp criticism through his newspapers Mooknayak, Bahishkrit Bharat and Janata. Many times he was accused of defamation or objectionable writing, which led to legal proceedings.

Freedom of the press was limited during British rule. In the articles in which he criticized the caste system, Hindu scriptures and the leaders of that time, he was charged with criminal defamation, inflammatory writing or intent to disrupt law and order.

In these matters, Ambedkar repeatedly argued that sharp criticism for social reform is a legitimate democratic right. If the law crushes this right, it becomes an instrument of oppression and not justice. This thinking is later reflected in the formulation of Article 19 (Freedom of Expression) of the Indian Constitution, where there is freedom, but with reasonable and clear reasonable restrictions, and not with autocratic repression.

protect self-respect

Even in the life of Dr. Ambedkar, there were some cases which were against discrimination and insults at the individual level, such as cases related to discrimination in job, salary, contract or social insult. Although most of such cases were not widely recorded or discussed, it is clear from the available references that he was not only a lawyer for the society, but also did not hesitate to adopt the legal path to protect his self-respect.

From court cases to constitutional debates

Dr. Ambedkar’s experiences were not merely theoretical. They were watching the courts every day to see how the law worked, how justice was delayed or delivered. On the basis of these experiences, he made many historical points in the Constituent Assembly. Here are some examples.

- Idea of Constitutional Ethics: Dr. Ambedkar repeatedly said that changing the law books will do nothing if constitutional morality is not developed in those in power and in the society. The injustice he witnessed in court trials led him to conclude that justice does not come merely from the language of the law, but from its honest application.

- Fundamental Rights and Reservation: Discrimination against the deprived classes in the courts made them understand that formal equality (same law for all) is not enough, protective provisions are necessary for real equality. This thinking came into the Constitution in the form of special provisions for reservation, educational opportunities and services.

- Independence of the Judiciary: He knew very well that if the judiciary is not free from political or social pressure, then there is no point in writing laws. That is why he always emphasized on the autonomy of the judiciary.

Also read: How many employees and how many planes does IndiGo have, how did the crisis arise? understand here