When we picture India’s independence movement, we often recall fiery speeches, defiant marches, and fearless revolutionaries. But behind the scenes was quietly knitting the nation together – the railways.

The British may have laid India’s rail tracks to tighten their grip and drain its wealth — but Indians transformed those very lines of steel into lifelines of resistance and unity. Far beyond a network for trade and troop movement, the Indian Railways became an invisible artery of the independence struggle, pulsing with ideas, protests, and the unyielding spirit of freedom. When we picture India’s independence movement, we often recall fiery speeches, defiant marches, and fearless revolutionaries. But behind the scenes, an unlikely hero was quietly knitting the nation together — the railways.

Tracks That Wove a Nation

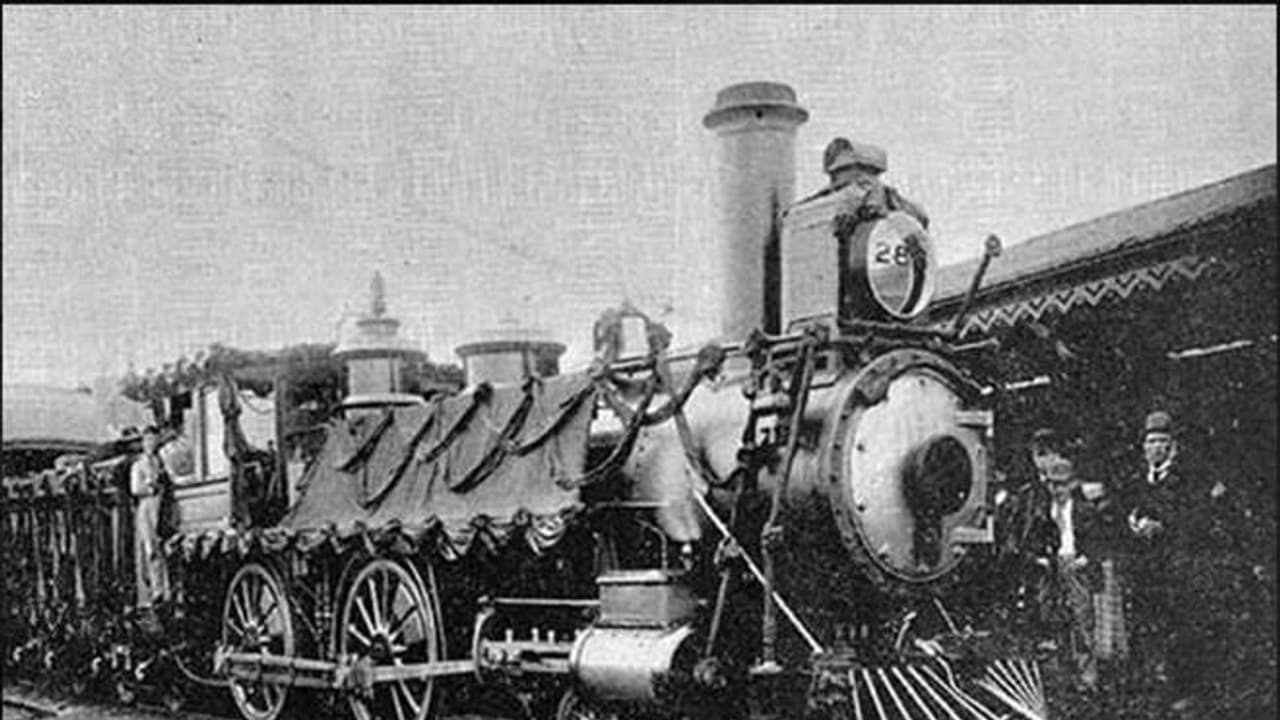

On 16 April 1853, when the first passenger train puffed from Bombay to Thane, no one could have foreseen its destiny. In time, the railways became more than an engineering marvel — they became a unifying force in a fragmented land. North met South, East met West, and millions experienced the reality of a connected India for the first time.

“The railway system linked far-flung regions and brought the people of India into contact with one another on an unprecedented scale,” writes historian Ian J. Kerr in Engines of Change.

With the steel veins of India throbbing with movement, ideas began racing from town to town. Newspapers, pamphlets, and slogans for swaraj (self-rule) reached even the remotest corners. Freedom fighters crisscrossed the country to rally support, spark protests, and ignite movements.

The Non-Cooperation Movement (1920), the Salt March (1930), and the Quit India Movement (1942) all drew strength from the reach of the railways.

Mahatma Gandhi’s third-class train journeys were more than travel — they were missions to connect with the common man, to understand the heartbeats of villages, and to craft an inclusive vision for a free India.

Rebels on the Rails

Trains were not only for connection they were also channels of resistance. Revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekhar Azad used them to evade British surveillance, moving covertly between cities. Sabotaging tracks became a weapon to disrupt colonial supply lines, and railway stations turned into political battlegrounds where protests, resolutions, and police crackdowns unfolded.

From Howrah to Mumbai VT, from Lahore to Allahabad, these hubs became stages for defining moments in the freedom movement — no longer just stops on a journey, but symbols of the colonial machine Indians sought to dismantle.

The railways were also a powerhouse of labour — one of the largest employers in colonial India. With this workforce came the muscle of collective action. Railway workers were among the first to unionise, their strikes echoing with political demands as well as calls for better wages.

The All India Railwaymen’s Federation, born on 16 February 1925, aligned itself with the Hind Mazdoor Sabha and backed the independence cause, proving that industrial might could be a weapon for freedom.

In one of history’s greatest ironies, the very system designed to exploit India’s resources became a tool to break colonial chains. As Christian Wolmar observes in Railways and the Raj: “The railways, intended to strengthen British control, instead ended up encouraging nationalism and undermining colonial rule.”