New Delhi: Director Rohan Sippy talks about Criminal Justice, Deepika Padukone and Sholay. Rohan Sippy, son of renowned director Ramesh Sippy, feels his father did not get his due. He also opined over OTT content and shared that it should create more content that appeals to the whole family.

Q. You’ve seen Pankaj’s journey—the way he’s becoming popular with the masses and on OTT. What is his X factor? How is he able to connect so well with audiences?

Rohan Sippy: I think he’s a very honest artist and human being. That quality can’t be faked.

Even when we were working with new actors—Khushboo and Atma Prakash, who are playing his wife and brother-in-law—he was so generous with them. He’d say, “You do this line, it’ll look nice.” That quality, which is very sincere, I believe comes from wanting what’s best for the scene and the show.

And that’s just his nature. Even when it’s not related to film, you’ll be able to spot that quite soon when you see him. I think the audience can sense a glimpse of that in Criminal Justice, and there’s a lot of affection for that.

The rest, of course, is that he works really hard on his craft—on how to execute scenes. The end result looks effortless, but it takes a lot of hard work, and he’s a big part of that. I’d say he’s a team player, which enhances everyone else’s results.

Q. We’re looking at your résumé. Your interest in crime stories—when did it grow, and how?

Rohan Sippy: I think the credit for that goes to all the platforms, because they’re the ones who believe that this genre—action, crime, thriller—is the most in demand on OTT. So naturally, the opportunities are greater in those genres.

I found it interesting because I had never experimented with them in my films. So it was a chance for me to explore a new genre—and that’s how it began.

There are two things, though. One is that the characters have to be really strong. I did Shekhar Holme with KK Menon—it’s another version of Sherlock Holmes. Along with the investigation, the experience of having fun and spending time with the character is important.

In this case, with the character of Madhav Mishra and a legal drama, we feel that. It’s not just about focusing on the plot twist; it’s also about how we arrive at it, how the characters present themselves, how they discover or figure things out—that makes a big difference. And this is a genre that is loved across the world.

Q. Yes, it’s a very popular genre globally. Why do you think that is?

Rohan Sippy: I think every season strikes the right balance. There’s a certain familiarity with the characters you’ve already connected with, but along with that, you’re introduced to a new world and new characters. Like this year, we had Surveen Chawla and Zishan—such great actors we got to tell the story with. That balance is key.

Sometimes in shows of other genres, people start to feel that the characters are stretched beyond their time. But here, it’s a new case every year, so there’s a freshness to it. And at the same time, there’s a blend of familiarity—like, “Oh, now Madhav Mishra’s life also includes his brother-in-law.”

Some new elements are introduced, and a lot of continuing elements are also there. You spoke about Surveen Chawla—I think she’s really come into her own. Through OTT, people have discovered her. As an artist, she has grown and evolved. Probably cinema didn’t give her that opportunity.

Q. What’s your take on Surveen Chawla—both as an actress and in your show?

Rohan Sippy: Surveen is terrific. I had been looking for an opportunity to work with her, and I think what you said is exactly right. In a 120-minute film, there’s very little room—especially when you move beyond the lead actors. They get very limited screen time, there’s very little breathing room. But in a show, it’s all about how an actor can contribute in a scene. It’s about how she takes a look, a pause—and I have the time, in the edit, to give that moment space. In a film, you’d immediately cut to the next plot point. That makes a big difference.

You see it in other shows—I won’t name them—but actors who have major star presence on the big screen often don’t hold on OTT. Because OTT is not about glamour shots, with lighting and backgrounds. It’s actually about holding on to an actor and beginning to understand what they’re feeling.

And only a good actor can express that—and that’s exactly what she does.

This season, her part was very difficult in terms of performance. You’re standing in court for six days, not doing anything—and that too requires physical discipline.

So, I think it was a great opportunity to start working with her, and I really hope we can continue. I’m so happy that, towards the end of the series, along with Pankaj, she was getting the recognition she deserves—and it’s overdue. Someone like her is invaluable—especially on an OTT show.

Q. At the time when your show is number one, a lot of people feel that there’s a plateau approaching—a saturation setting in. What do you think the problem is? People say that the OTT space is becoming saturated. Why do you think this perception is growing? And if it is happening, then why? What do we need to do?

Rohan Sippy: Well, we ultimately have to analyse the audience and understand what they actually like—and maybe take a few risks. What’s possibly happened is that many creators come from a more restricted background or perspective, whereas India has a vast diversity and deep traditions. Maybe we need to explore more and bring in people who can tell different kinds of stories.

I think we’re at a transitional phase. Initially, there was a lot of excitement—everyone wanted to invest. Big platforms were putting in a lot of money. But now, perhaps the reality that subscriptions have their limitations is being understood. Income will need to be generated via advertising.

And if you’re generating income through advertising, then you have to make shows for a wider audience. You might personally like something that appeals to a niche group, but that may not be viable at the moment.

So now we have to look at what can be enjoyed on a broader scale—where advertising helps sustain the content. It might end up becoming more like what television was five years ago. We don’t know yet.

Technology plays out in so many different ways, and it’s hard to keep up because it’s very dynamic. I think it’s always an experiment. Like in the film world, there’ll be a certain theory—and then one Friday, something like Saiyaara comes along and suddenly brings in a completely new theory.

We’re waiting for that kind of breakthrough to happen here too. We need to find that one show that really connects with people. The other thing is that we should start creating more content that appeals to the whole family. Initially, the thinking around OTT was that content should be made for individual viewing—for people watching alone in their rooms or on their phones.

But obviously, the bigger opportunity is in making something the whole family can enjoy together. Advertisers will like that too. I think there are many opportunities—we just have to figure out how soon we can discover them.

Q. Now that you’ve made the shift and belong to OTT, do you think the pressure of box office numbers contributed to that shift? And does it help you now—that there’s no box office pressure and you can focus on making the content you want?

Rohan Sippy: I would say that pressure is obviously not there. The pressure I put on myself, in that sense, is to do a show good enough that the channel wants to make another season. That’s the equivalent of a box office hit for me. So that’s always in my mind—that the venture should be strong enough for audiences to appreciate it, and for the channel to think it’s worth continuing. So yes, that’s the pressure—or whatever you’d call it—that I place on myself: to do it well enough that the channel at least considers another season. At the end of the day, it’s a business. Whether it’s box office or OTT, someone is investing money, and they deserve a return on that investment. If it doesn’t generate a return, then naturally the show won’t continue, and the industry itself won’t have a sustainable chance at growth. That responsibility is always there. It doesn’t mean that’s all you think about, but understanding the boundaries—that you’re operating within a business—is very important.

It’s an exciting business. It’s given us new kinds of stories, and actors like Surveen and Pankaj ji now have the opportunity to become stars. There are so many positives that come out of this space. But we also have to recognise that we must deliver for the people who are investing in it. It’s a process—we have to keep going back and forth. The platforms have to keep giving us their guidelines, and we have to keep pushing the idea that they must take some risks. But those risks need to pay off. That’s important.

Q. Do you think OTT platforms avoid taking risks and prefer to stay in their comfort zones?

Rohan Sippy: No, I think there’s always a mix. Criminal Justice, when Hotstar decided to start it, was a risk. Nobody knew what OTT would become back then. I think risks do happen—it’s just a matter of how you present them, and how the platform is looking at it at that particular time. All these things are very dynamic. Just like in the film business—every Friday, some new reality would come into existence. Similarly, on OTT, a Scam will work, or a Panchayat will work—and it opens people up. They start thinking, “There’s great potential here too.” It’s always a process of discovery. You’ll never be able to predict it a hundred percent. And that’s what makes it exciting.

Q. Abhishek Bachchan—he’s also becoming an OTT star, and he’s doing so much work on these platforms. How do you view someone like Abhishek, who’s Bachchan’s son, and the kind of characters he’s now playing?

Rohan Sippy: I think it’s great. You have to keep growing—as a human being, and as an actor. I think he enjoys watching some of the best shows and films, and this is a chance for him to participate in that space. Good actors often enjoy OTT more, because it offers a canvas that’s very actor-friendly. It’s great that he’s not caught up in a fixed idea of what being a successful actor should look like. You have to keep creating that definition for yourself. And look at his father Amitabh Bachchan —he took a step toward television and completely reinvented himself after an already amazing career. He chose to do something that made people scratch their heads and wonder, “How is he doing television?” No one could understand it at the time. But he redefined the medium, and he redefined himself. So, I think, when you’re willing to take risks—when you have that creative excitement and the chance to reach a new audience—that’s when you’re truly rewarded. I’ve seen your journey.

Q. How do you see it when you look back—from where you started to where you are today?

Rohan Sippy: I’m just very grateful. I’ve had so many opportunities—first in films, and now on OTT. The number of people I’ve had a chance to collaborate with, from writers to actors—it’s been a wonderful journey. The last few years have been especially exciting because the volume of work you have to do really draws on all your experience. In film, you learn so much—but now you get to put all of that into practice. I have to try to achieve film-level quality at four times the speed. If we used to do two pages a day in film, now we have to do eight. So how do you do that without compromising? That becomes an exciting challenge: getting the whole crew, the whole unit, to work together at such a high level of quality and speed that you can actually pull it off. It’s always a fun exercise. And as you gain more experience, you also know which tools to use, how to work smartly, and how to make sure you don’t compromise. Then there are the stories themselves. When I started out, I couldn’t have imagined that we’d be telling stories across so many genres. Sometimes I look back and feel we’ve lost the art of telling a great Hindi film—that kind of storytelling has its place, and I don’t think we’re doing enough of it right now.

So, I do hope the pendulum swings back in that direction too—that we get a few great films that the whole family wants to go out and see and enjoy, across the country, no matter where they are. That was the beauty of Hindi cinema: it could bring us together on a Friday, and beyond, to share in the joy of experiencing a lovely film that truly touched your heart. So hopefully, that spirit comes back as well.

Q. Just when people thought that action is what works—when it was being defined as the “era of action films”—Saiyaara comes along and defies all the jargon around that. What’s your thinking on that?

Rohan Sippy: I think it’s simple. William Goldman said it a long time ago—his first rule of Hollywood was: “Nobody knows anything.” No one can really predict anything. And secondly—hats off to the producers for their conviction. They put money behind newcomers, with an experienced director. That’s what used to happen in our time as well—Rajkumar Santoshi directing Bobby Deol in his debut, and so on. Newcomers were given the biggest platforms with the biggest directors. That’s how you introduced new actors to the audience. And it worked. Not every film was a hit, of course—but so many new talents entered the industry because producers mounted their launches the right way.

So again, a big congratulations to Yash Raj. Until now, they haven’t actually launched too many newcomers over the years—but this was a great burst of energy for the whole film industry: to take two fresh faces and give them a full-fledged film. And it’s not just an urban phenomenon—this film has crossed all boundaries. That’s exactly what the industry needs. You need fresh blood every few years. It’s unbelievable—it’s been 35 years since Salman, Aamir, and Shah Rukh entered the scene. So we do need many, many more young actors to come in, tell stories, and connect with younger audiences.

Q. What did you think of Ahaan? Because Ahaan Pandey is the new rage right now.

Rohan Sippy: You can’t really explain a phenomenon. Obviously, he’s done a wonderful job, and the director has handled him beautifully. The music, the story’s connection with the audience—it’s all come together. Beyond that, you can’t explain it. Any analysis would be foolish. I don’t think there’s a formula for this—it’s just the right mix of everything. And at the heart of it is his sincerity, his energy. He’s also worked for a long time to get this opportunity. I think good things happen when they’re meant to happen.

Q. When will you make another film for the big screen—for 70mm? Or do you want to continue writing more for OTT?

Rohan Sippy: I would love to. I’m actually working on two to three ideas right now. Obviously, we’re seeing that it’s a very challenging environment for film production—which I think is a good thing. It puts a lot of pressure to get your budgets right, your story right, your casting absolutely right—so that everyone backing the film has a real chance to benefit. At one point, I think it had become too easy to start projects based on the assumption that money would flow in from streaming or satellite rights. It became almost a backward calculation—if you did something with a particular actor, returns were considered guaranteed. Now, there are no guarantees. So, let’s really go out there, make a film we believe in—a film we believe the audience will genuinely be excited to see. I think that’s good pressure. It forces us to raise the bar for the quality of our films.

Q. Do you think sometimes the diktat from OTT platforms weighs heavily on producers—like the rule that films must have a theatrical release before coming to OTT?

Rohan Sippy: Those are just the rules of the marketplace. Every market has its own dynamics. When there are more buyers and fewer sellers, the sellers have the upper hand. But now, with so many producers (the sellers) and only a few platforms (the buyers), it’s natural that the platforms get to dictate terms. And why not? That’s the nature of any market. They’ve suffered losses too. A good market keeps correcting itself. You go through a phase like this, a correction happens—platforms may reduce in number because if it’s not profitable for them, why should they continue in the business? There might be mergers or consolidations, and suddenly you have fewer buyers. At that point, you need to make your product more attractive, because you’re now competing with many more sellers. There are twenty people out there with the same pitch, whereas earlier, we had more options to sell to.

I think we’ve all been trying to understand this since the time of Adam Smith.

Q. When we talk of legacy and your name comes up, how would you like to take it forward? You are taking it forward, of course—but what would be your way? And how much does legacy matter in today’s time?

Rohan Sippy: I think, for me, it does matter. My grandfather entered the business almost 75 years ago. My father’s been working in it for nearly 65 years. So yes, it’s definitely a point of pride. But I try to carry it forward through my actions—not by talking about it, but by remembering that it’s a privilege to be working in this industry. Every day, I go to set with a crew of a hundred or a hundred and fifty people. I get the chance to work, to share what I know, and—just as importantly—to learn from them. On my last shoot, there was a small scene between a doctor and a patient. The actor playing the patient had just one scene. He came up to me and said, “I used to work as a spot boy when Sagar was being made.”

That moment meant a lot to me. It felt like such a special connection—to know that in some small way, he had worked with both my father and grandfather. These are the moments that make the whole journey feel worthwhile. And the more time you spend in this industry, the more often you meet people—or their parents—who were part of something related to your own story. It keeps the legacy alive for me. And as long as I can continue their work and carry their memory forward, I think that’s a beautiful thing to do.

Q. This is a bit of a clichéd question, but—if you ever wanted to remake a film by the Sippys, which one would you choose and why?

Rohan Sippy: That’s a tricky one—because honestly, I think it’s almost a fool’s errand to remake a good film. Especially when it comes to my father’s films—he was such a complete director that very few of his films feel like they could be improved upon. There are some where you can see, okay, the story is good, the film works, and maybe I can add twenty or thirty percent to elevate it—but still, that’s not easy. There are some really fun films in that legacy, but to reinvent them the right way for today’s audience? That’s no small task. One film I do love is Seeta Aur Geeta. It’s such a fun comedy. That might actually be a great one to revisit—if we could find the right way to make it feel fresh for now. Chaalbaaz was already made as a kind of remake. Others have attempted versions of it. So maybe something like Seeta Aur Geeta could be a really fun remake to do.

Q. There is, of course, an advantage to the surname you carry—Sippy. But was there ever a disadvantage too?

Rohan Sippy: Never a disadvantage. It’s always been an advantage to have that name. People have only had positive associations with my father and his work, so I’ve always received the benefit of the doubt. Even today, I feel that blessing is still very much there. It allows things to begin on a positive note—people are in a good frame of mind when they first make contact. And from there, it’s just about building on that, strengthening the positivity in the way we interact and work together. That’s really what the name does—it gives you a very nice blessing.

Q. Do you think Ramesh ji got the recognition and accolades he truly deserved? As a son, what do you feel?

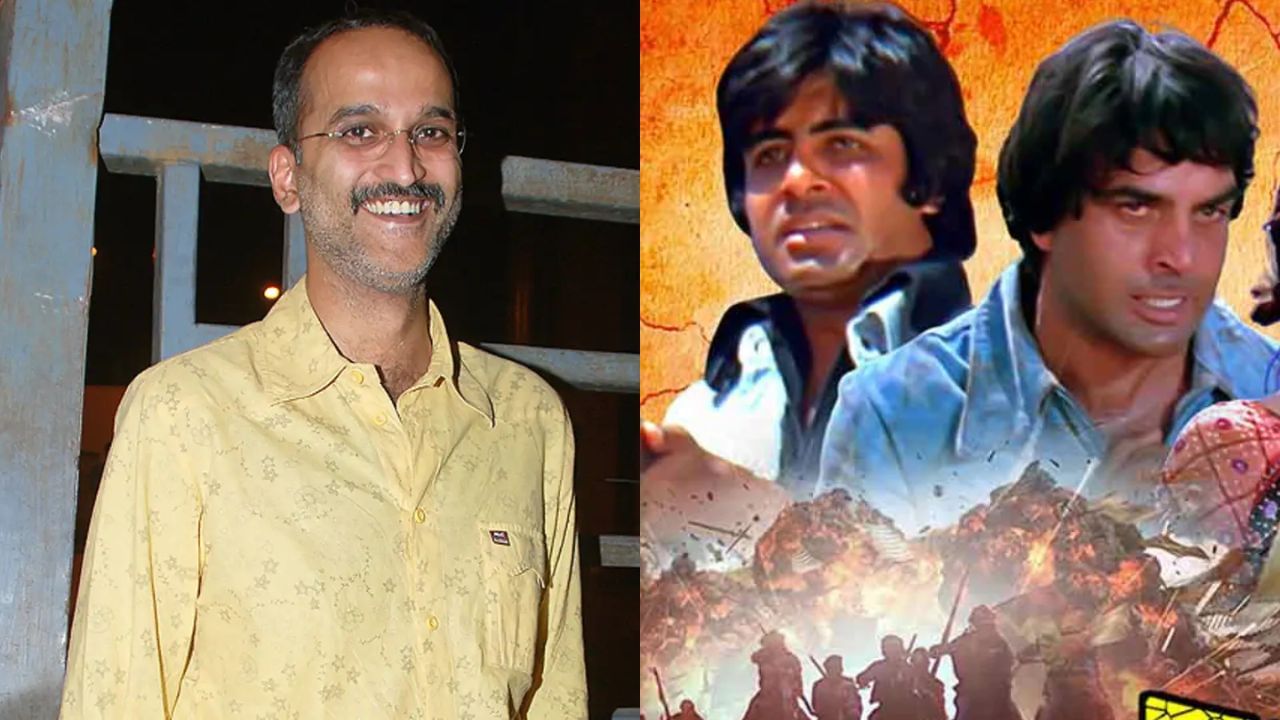

Rohan Sippy: There are two parts to this. I don’t think he did. But for me, what that really reveals is that accolades and awards don’t mean much. The real accolade is what you get from the audience. The fact that Sholay—a film that’s still regarded as one of the greatest ever produced in an industry that’s over 120 years old—is celebrated to this day… that’s the real salute. Now, the rest of it—those absurd things, like not even receiving an award when it released—only reflects the pettiness of the awards and the people giving them. They’re the ones who become small. My father doesn’t get diminished by that. What truly matters is that Sholay endures in the public’s imagination. In our culture, it has become one of the epics we all know—like our ancient epics. You could say that Sholay is one film that has achieved a stature close to that. That is the real reward. And the fact that so many people who have done extraordinary work in their careers still consider Sholay among their greatest achievements—that is legacy. Whether or not others acknowledged it only reflects on them, not on him.

Q. Coming back to fifty years of Sholay—first of all, what does Sholay mean to you as a filmmaker, and then as a son?

Rohan Sippy: As a son, I obviously feel incredible pride. And it literally happened in my childhood, so I got to see it as a very young child. And the way my friends reacted to it—there can be no prouder thing for someone, to feel that: oh wow, my dad did this. You almost couldn’t believe it. It kept growing with time, and you observed it almost like a younger sibling—growing up and growing bigger all the time. And as a filmmaker, there are so many lessons in it. Even now when we are writing, there are often times we say, “Let’s do it like a scene from that film.”

You get so many clues of great writing and how they cracked the characters. All of that becomes a shorthand for us to solve our problems when we’re writing. The two ends of Sholay — people talk about. I think if you read the book that Anupama wrote, also—there was this ending that was always the reason for making the film the way they did, the ending they had. It was a very powerful ending.1975—the Emergency is happening, all of that pressure—and finally, a film that was undertaken with the principle that they won’t compromise on anything… my father had to compromise on the one thing that he was very excited and passionate about. That the meaning of the final one line of the film—he wasn’t able to convey that to the audience. That must have been a brutal feeling for him. After all this effort, and having overcome all the obstacles in front of the government—you now have no choice. They have so much power that you can’t fight for what you want.

It will be incredible if they manage to—I have no idea—but it’s an incredible opportunity to share what, not just him, Salim sahab, Javed sahab, all the actors… they all worked so hard with the excitement that this is the climax that we wanted to see. And actually now, you’re going to get to share it with an audience today. I think it’s an incredible reason to go and see the film again.

Q. So, did your father discuss this with you? The conflict that was on?

Rohan Sippy: No, because I was very small at that time. And then a while later, when Anupama was researching the book, we used to hear that discussion. That is the time when it came up.

Q. Which ending is more convincing for you?

Rohan Sippy: I’ll watch it and then I can say. But it is obviously the one that the writers and director had visually intended—that would be very interesting to see. It has a certain kind of poetry, from where they start and then reach the ending. That makes sense. The sum up of the whole story has a different power, I believe. But I have not seen it. I would love to see it and then react.

Q. It has been fifty years of Sholay. What comes to your mind?

Rohan Sippy: Golden! It is a golden anniversary for one of the most enduring films. So, it’s a special anniversary. You know, Deepika, she’s someone who is very vocal. She talks about depression, she talks about rules, she has spoken about eight hours of work, she walked out of a film, because of certain reasons as an artist.

Q. Do you think it’s right for an artist to do that? In today’s time?

Rohan Sippy: See, it’s entirely valid. You must discuss this in anything—forget about actors and films. In any job you’re contracted to come on board, you’ll discuss the terms of working. If it suits you mutually, you’ll agree. If it doesn’t, you won’t. I don’t think there’s anything wrong at all in the way of asking for anything. If it doesn’t suit me as a producer, I won’t agree to it. That’s the bottom line. And obviously, if you’re worth more to people, they can accommodate you in different ways. Even someone like Pankaj ji doesn’t like to work twelve hours. And I understand—he puts so much effort in. I can make a day work with eight hours or ten hours with him. So, it’s not at all just eight hours. You come in, you prep, you go at the end of the day—so you might work eight hours, but your day might be twelve hours. After that, an actor also has to prepare for the next day. Those eight hours don’t allow you to read and understand or question things. You have to go out and perform.

So, when are you going to prepare for the performance? That also has to happen in the twenty-four hours of the day. So, I think there’s no fixed thing, that it’s wrong to ask for an eight-hour day. A producer can say, that I have to have you work for eight hours, otherwise my budget won’t work.

Q. So, Deepika saying that she wants to work for eight hours as an artist— is that correct or not?

Rohan Sippy: See, it’s no rule. It’s a discussion between the producers and the artist. One is: okay, I like the script. And the second is: how we’re going to make it. It could be said that this is to be made in a hundred days, and in those days we need twelve hours every day—whatever it is. And then the artist can say that she is unable to give that much time—whatever it is. There’s nothing right or wrong about one person saying one thing, or the producer reacting a certain way. They have to both agree, and it has to make sense for both of them. She has worked now for fifteen or seventeen years. She has totally earned the right to say that this is how she wants to work. There’s no controversy in this. And a producer has the right to say what they feel is right for them, what is practical for them. They can renegotiate or come to a middle ground—or they don’t. There’s nothing about someone being right and the other person being wrong in this.

There are so many occasions in the world where two people don’t agree. They might agree on one aspect, which is the creative side, but when it comes to execution, they don’t whatever their commitments to work, family, whatever their priorities are.

Q. You’re a director. And a story has been circulating since morning that Raanjhanaa’s end has been changed using AI. That has made the director and the actor angry. You’re a filmmaker, what is your point of view. That it’s out of the director’s hands and he cannot do anything about it. It was an emotional end that should have been kept, but using AI the producers have changed the ending.

Rohan Sippy: Unfortunately, whatever we feel is correct morally, unfortunately or fortunately, we work on the basis of contracts, so obviously, when you’re a more successful director you can ask for things, like the final cut of the film to have your vision. So many Hollywood films are not released here because the director has a say in what gets cut off from the film, so it doesn’t get released in any particular territory. This is a process by which unfortunately you feel bad for any storyteller whose story is being changed but what will happen is that we all have to become more clever when it comes to contracts, we have to insist that the final version cannot be changed or tweaked in any manner. If it is not defined, then it becomes a gray area that someone can take advantage of and then you cannot say that they are doing something illegal. It may feel wrong to you but it is not illegal.

Q. So there has to be a clause in the contract to protect that?

Rohan Sippy: That is what will happen with technology growing as it is. Lawyers will get better incomes, they will find more ways to protect you and create opportunities for themselves. I think that’s what will happen. Unfortunately there will be some films or filmmakers that might suffer in the meantime. They will think that this wasn’t there when we signed the contract and now such a thing is happening. And it will feel unfair. I can totally sympathise with them. But the best way is, I mean going back you can’t do much, but going forward we should try and ensure that producers guild can also protect people’s rights. So that the organisation is working towards something which is practical for all involved.

Q. Before you go—Aamir has opened a new avenue. He is not going to OTT but releasing his film directly on YouTube. What is the signal that one gets?

Rohan Sippy: The signal you get is that he wants a little more control on his release, which is fair enough. It all again depends—if the film is a runaway success, it will gain more momentum. If it falls short, people will think, “If he had sold it the normal way, he would have gotten fifty crores more.” I don’t know the exact numbers. But if it feels like you’re getting fifty rupees instead of a hundred, then people will question—why take that risk? So, it’s always a question that will be answered by the end result.His instinct is good—he wants to keep things slightly more open. There’s also this subconscious thing in the audience’s mind—that in eight weeks they’ll be able to watch the film at home. So why go out to see a film, except for maybe one or two they really care about?

The larger audience has lost that habit of going to the theatres, because technology now brings content home within two months. That’s the debate.In the West, they keep films in theatres for longer, so that gives cinemas more of a chance. But again, these are all market forces—every country has a different dynamic.What you don’t want to see is that, because of this, production reduces. That’s the real danger. If it reduces too much, we won’t have enough films to run in theatres. Already we’re seeing old films come back during gap weeks when there are fewer releases. That’s not a good pattern overall. We have to create an environment where exhibitors feel that new cinema is worth showing. Right now, it’s the opposite. Actually, it’s quite similar to the situation when Hum Aapke Hain Koun was released. Back then, piracy created pressure on the industry, cinemas were shutting down. We’re entering that kind of cycle again. Hopefully, with Saiyaara and a few other good films, we can turn the mood around—bring back some optimism that even cinemas can be profitable, and make it worthwhile to invest in them. That’s something we can hope for. But it’ll take a bunch of films to achieve that.

This was never an easy business. When Sholay was made, income tax was at 97%, and tickets had an entertainment tax of 177%. And despite all that, they managed to make films. We have to gear up for the fact that in difficult times, you have to rise to the challenge—and do better.