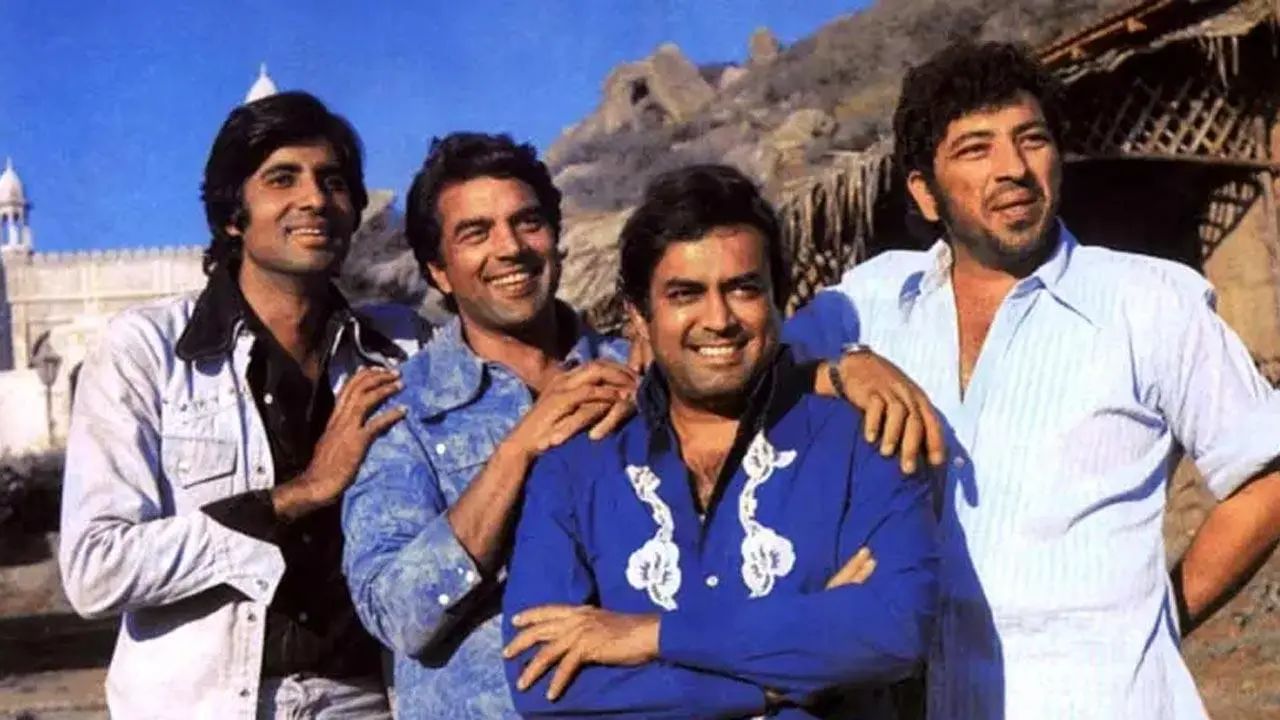

New Delhi: Fifty years, and India’s greatest blockbuster still rides tall — not just on its stars, but on its sounds, shadows, and the unsung hands that built it.

It wasn’t just a film. It was an encounter. A meteor striking the silver screen, announcing — this is what cinema should feel like.

Not immersive — inevitable. As if Ramgarh had always been there, and we simply wandered in mid-saga.

For some, it was 70mm at Plaza. For others, stereophonic sound ricocheting while Gabbar’s boots scraped gravel. Ask anyone who saw Sholay in 1975 and they won’t start with plot. They’ll start with impact.

Because Sholay didn’t just play. It rolled in like a dust storm. And that storm wasn’t driven by stars alone. Frame by frame, sound by sound, it was fired by craftsmen — many barely remembered — who laid the fuel under the legend.

The Eye That Told the Story

Dwarka Divecha didn’t “shoot” Sholay. He painted it with light.

Radha’s sorrow — silent, bathed in midnight blue, hurricane lamp flickering — says more than dialogue ever could. Then the sun-baked hills where dacoits descend — rust-red, white-hot. Divecha could shift from stillness to chaos without losing the shot’s soul.

His camera lingered when needed — on shadows, on boots — then burst into pursuit with a dancer’s grace. Each frame carried subtext. This was visual storytelling before the phrase became fashionable.

Sound as Memory and Omen

Jayant Pathare’s engineering and R.D. Burman’s instinct made Sholay’s soundscape unforgettable.

Radha’s melancholy lives in the harmonica — played by Burman himself — the only bridge between Jai and Radha. Then Mehbooba Mehbooba: a fever dream, danger pulsing through every beat.

Atmospherics were never filler — the train’s chug in rhythm with galloping hooves, the metallic dread of a cotton thresher as a corpse returns. Every sound was a tool of tension.

Cut to Life, Cut to Death

M.S. Shinde’s editing wielded silence like a weapon.

Gabbar swats a fly. Cut. A horse trots into Ramgarh with Sachin’s limp body draped across it. No music, no speeches — just dust and consequence.

Or Gabbar’s “Holi kab hai?” days before the raid. By the time Holi arrives, it’s not colour — it’s carnage. Shinde turned waiting into dread.

The Terrain as Character

Ram Yedekar’s design turned Ramanagara into a mythic battleground.

The bridge, the well, Gabbar’s rocks — not just locations, but narrative weapons.

And when destruction came, M.B. Shetty’s pyrotechnics made it real — explosions timed to camera, choreography, and dust. No CGI. Just live detonation, sweat, and risk.

The Man Who Didn’t Shout

Ramesh Sippy directed without stamping his ego on every frame. Gabbar enters late. Silences breathe. Stillness is respected as much as spectacle.

Behind him, G.P. Sippy kept the faith through delays and overruns — no panic, no penny-pinching. That’s rare.

Salim–Javed—Populating an Epic

We remember the big three — Jai, Veeru, Gabbar — but Salim–Javed filled Ramgarh with characters who refuse to fade.

Asrani’s Hitler-jailer. Jagdeep’s serial liar Soorma Bhopali. Kaliya’s trembling defences. Mausi’s matrimonial cross-examination. Keshto’s boozy gang. Sambha, immortalised in three words.

They weren’t side notes. They were oxygen. They made Ramgarh feel inhabited, not constructed.

The Dance That Wasn’t Just a Dance

Mehbooba was distraction as strategy. Choreographed by P.L. Raj, Helen’s performance syncs perfectly with Burman’s beat, hypnotising the village — until the ammunition goes up in flames. Entertainment and entrapment in one sequence.

The Men Who Made the Mayhem

Beyond Sippy’s set, second-unit directors Mohammed Ali and Azim bhai — plus Hollywood stuntmen Jim and Jerry — handled action sequences with military precision.

Bhanu Athaiya’s costumes reflected terrain and temperament: Gabbar’s guerrilla gear, Jai’s sparse denim, Basanti’s bold-eyed defiance. M.K. Mehra’s make-up aged Thakur and scuffed the dacoits into realism.

Sholay Wasn’t Shot — It Was Built

The stylists who dirtied Gabbar’s face. Light boys who hoisted gels on rocks. Carpenters who raised Ramgarh plank by plank.

It was made like a fortress — and that’s why it still stands.

So, fifty years on, roll the credits again. Not as formality, but as a roll of honour. Because legends don’t just happen. They’re built by hands you never see.