New research reveals how deep-sea mining waste could devastate the ocean’s twilight zone. Learn how these sediment plumes create “junk food” for zooplankton, threatening the entire marine food chain.

Researchers from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa have discovered that deep-sea mining might seriously affect ocean life, especially in the “twilight zone,” one of the most important and least understood parts of the sea. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, reveal that waste from mining could disrupt the food chain in this sensitive region of the Pacific Ocean.

What Is the Twilight Zone?

The twilight zone is located between 200 and 1,500 metres below the surface. While sunlight hardly reaches this depth, it is home to billions of tiny, drifting organisms known as zooplankton. These creatures form the foundation of the ocean’s food chain, feeding on small animals like shrimp and fish, which are then eaten by larger species such as tuna, seabirds, and whales.

The study focused on the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a vast area between Hawaii and Mexico that is rich in valuable minerals like cobalt, nickel, and copper. However, the discovery of these minerals has attracted interest from mining companies, prompting scientists to worry about the potential environmental harm.

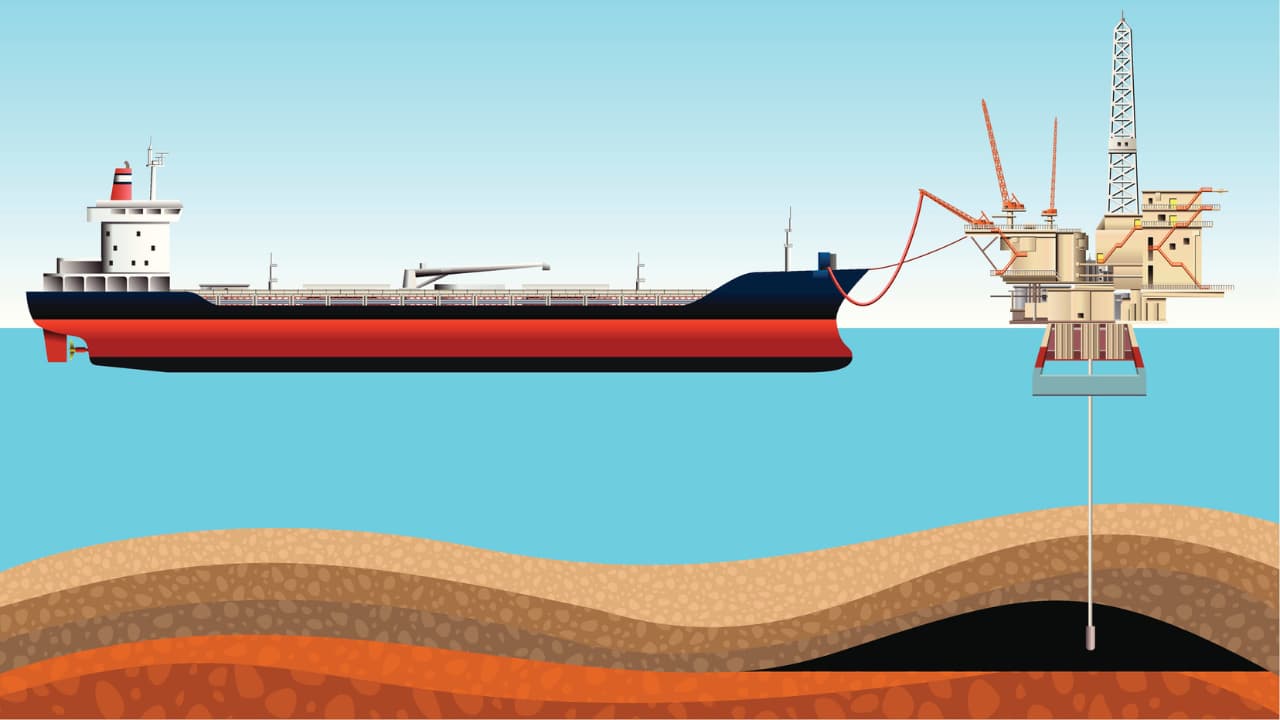

Mining Waste Pollutes the Ocean

When minerals are extracted from the seafloor, sediment and waste are sent back into the water, creating cloudy plumes of fine particles. According to lead author Michael Dowd, a graduate student in oceanography, “When the waste released by mining activity enters the ocean, it creates water as murky as the mud-filled Mississippi River. The pervasive particles dilute the nutritious, natural food particles usually consumed by tiny, drifting Zooplankton.”

This murky water, described by Dowd as “junk food sediment,” may initially appear harmless. However, the researchers found that it could have far-reaching consequences. Zooplankton consume this low-quality sediment instead of their usual nutrient-rich food, which in turn reduces the nutrition available to the creatures that feed on them, such as small fish and shrimp. Over time, this disruption could impact the entire ocean food chain, starting from the smallest organisms up to the largest predators.

Measuring the Impact

The researchers examined samples collected during a 2022 mining experiment in the CCZ. They found that the waste particles released into the water had significantly fewer amino acids compared to natural food particles found at the same depth.

The team estimated that about 53% of zooplankton and 60% of micronekton, small animals that feed on zooplankton, could be affected by such mining activities.

A Delicate System in a Nutrient-Scarce Environment

Life in the deep ocean has adapted to extreme conditions, where food is already limited. Many animals in the twilight zone, such as squid, krill, and jelly-like creatures, migrate upwards at night to feed near the surface and return to the depths during the day. This daily movement plays a key role in transporting carbon from the surface to the deep ocean, helping to regulate Earth’s climate.

However, if their food source becomes less nutritious, these animals may struggle to survive or reproduce.

Broad and Long-Lasting Consequences

Although deep-sea mining has not yet started on a commercial scale, the risks are already becoming evident. Around 1.5 million square kilometres of the CCZ are currently licensed for exploration. If large-scale mining begins without proper safeguards, it could cause long-term damage to ocean ecosystems, even in areas far from the actual mining sites. For instance, species like tuna that migrate through the CCZ could be affected, which could eventually impact global commercial fisheries and seafood supplies.

The Need for Stronger Regulations

Currently, there are no international rules governing where or how deep-sea mining waste should be released. The study’s authors stress that decisions about where mining waste is discharged must be made carefully. The effects can vary with depth, and releasing waste in the wrong location could harm marine life from the surface all the way to the seabed. They hope their research will help guide policymakers at the International Seabed Authority and other global organizations that are currently discussing mining regulations.