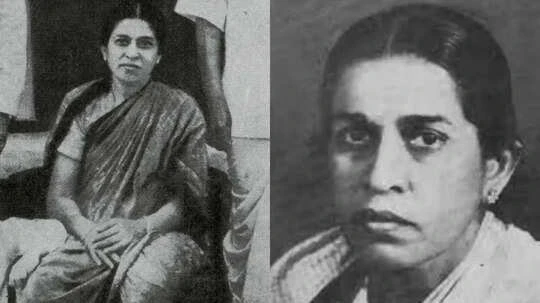

If you’ve been scrolling through social media recently, chances are you’ve come across conversations about forgotten women freedom fighters.

With history textbooks often giving them just a passing mention, there’s a growing buzz to rediscover and celebrate their contributions. Among these unsung heroines, one fiery name stands out-Umabai Kundapur, the young widow who rallied 150 women volunteers (yes, including widows!) to march shoulder-to-shoulder with Gandhi during the 1924 Belgaum Congress Session.

At a time when women were expected to stay within the four walls, Umabai was rewriting the rules-without waiting for anyone’s permission.

A Spark in the Streets of Bombay

The year was 1919. India was reeling from the draconian Rowlatt Act and, soon after, the horror of Jallianwala Bagh. On the very streets of Bombay, 27-year-old Umabai found herself swept into the tide of protestors. Just a year later, as thousands mourned Lokmanya Tilak, she found her own resolve hardening. Freedom was no longer an abstract idea-it was a calling.

Born into privilege, married at nine, and encouraged by her reformist father to study, Umabai knew education was power. And she was determined to use it not just for herself, but for society.

Breaking the Mould of Widowhood

Her life took a devastating turn in 1923 when her husband died of tuberculosis. Society expected her to retreat into silence. Instead, Umabai sharpened her voice. She took charge of her family’s press, supported a girls’ school, and began mobilising women for the cause. When others saw a widow in white, the freedom movement saw a leader in khadi.

Dr N. S. Hardikar noticed her efforts and made her the head of the women’s wing of the Hindustani Seva Dal. Imagine a young widow teaching other women military drills, camping, and spinning khadi-it was as revolutionary as it gets for that time.

Gathering 150 Women-Against All Odds

Umabai didn’t just stop at leading women in drills. She created an organisation-Bhagini Mandal-to educate and empower women. Her crowning moment came in 1924, when she pulled off what many considered impossible: convincing 150 women, including widows, to attend Gandhi’s Belgaum Congress Session. At a time when women stepping out without permission was scandalous, Umabai had engineered a quiet social revolution.

A Prisoner, a Shelter, a Fighter

History records that Umabai was imprisoned for months during the Salt Satyagraha. Yet even after her release, her setbacks multiplied-her school was shut, her press confiscated, and her organisation banned. Most would have broken down. Umabai doubled down.

She opened her home to underground workers during the Quit India movement, fed them, gave them shelter, and risked arrest every single day. When Bihar was hit by a devastating earthquake in 1934, she didn’t wait for aid-she travelled with volunteers to help victims. For her, freedom meant nothing if society wasn’t uplifted.

Recognised by Gandhi, Remembered by Few

By 1946, Gandhi himself recognised her courage and appointed her head of the Kasturba Trust, where she trained widows and destitute women in arts and crafts. Awards and honours followed after independence, but she refused them all. She insisted she had not fought for fame.

Vice President Venkaiah Naidu once summed up her legacy: “She selflessly served the people day and night, but always preferred to maintain a low profile.”

In an age where women leaders are still fighting for equal representation, Umabai’s story feels fresh, fierce, and oddly modern. She broke stereotypes long before hashtags and campaigns made it fashionable. She taught us that real revolutions aren’t always about swords and speeches-they’re often about resilience, community, and a refusal to accept what society dictates.

Umabai Kundapur wasn’t just a widow who defied expectations. She was a movement in herself. And perhaps it’s time we gave her the trending spotlight she always deserved.