In businesses, advisors and auditors serve different purposes; the former work to help companies drive growth, benchmark performance, creating operating models, support expansion, reduce costs, maximise profits, etc.

The latter is responsible for protecting the public interest by scrutinizing financial statements and assuring investors and broader stakeholder community on the financial health as reflected through the books of accounts. Both roles are essential to a healthy economy, but today they are increasingly intertwined in ways that weaken trust, especially as technology helps answer the obvious challenges and the global nature of private sector operations including complex accounting, structures and IT systems.

In India, the evolution of advisory and audit has been closely tied to governance reforms. After Independence, the government, through five-year plans and planning bodies, recognized the importance of advisory services. Following the liberalization of the 1990s, the Global Big 4 carved a niche in the Indian market with specialized consulting services in strategy, risk, and digital transformation. Since then, consulting expanded into sectors like ESG and Healthcare, growing rapidly with India’s digital economy.

But this growth has exposed structural challenges. Most believe for the largest firms, consulting generates the bulk of profits with services such as tax planning, strategy, and technology bringing higher margins and sustained revenue streams. In contrast, audits are often low-margin, tedious processes and increasingly under regulatory spotlight. Hence, when partners (directly or indirectly) in the same firm share both advisory incentives and audit responsibilities, the risks are apparent. Despite regulatory requirements or internal process – driven safeguards for audit independence, the perception of conflict remains real.

The problem is not unique to the Indian landscape indicating that the integration of audit and consulting services may result in diminished outcomes. Empirical research has shown that firms offering a broad range of non-audit services tend to produce lower-quality audits, which are associated with a higher likelihood of misstatements and a subsequent decline in investor confidence.

Since the early 2000s, corporate cases in the US have revealed how auditors, while simultaneously offering consulting services, have failed to perform optimally in their auditing practices. The US had responded to this trend with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which imposed strict limits on the services auditors could provide to their clients.

Similarly, in the UK, the Financial Reporting Council has mandated an “operational split” between audit and consulting practices to strengthen the independence of business operations. The EU is also actively debating the need for stronger structural reforms, including mandatory rotation of audit firms and tighter limits on non-audit services. Subsequently, in Australia, regulators have raised concerns about auditors’ reluctance to challenge their clients when consulting fees are at stake.

At the core of this global shift lies the recognition that consulting and auditing should be treated as separate entities, and economic dependence on each other undermines the quality and throughput of work. Today, India stands at a crossroads. The consulting industry in India is currently experiencing rapid growth, expanding from $7.8 billion in 2020 to a projected $24 billion by 2025. Many firms, , providing advisory and audit services under the same roof. This dual role threatens the sanctity of their operations and risks lowering the quality of both functions.

The National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA) has played an essential role in highlighting this difference, and has flagged the risk of a firm providing advisory or non-audit services to entities it audits (or related entities) because such dual role can impair independence, create self-review or self-interest, and undermine audit quality. As a national regulator established under the Companies Act, 2013, its key functions include monitoring audit quality, investigating misconduct, and setting rules to safeguard the independence of auditors.

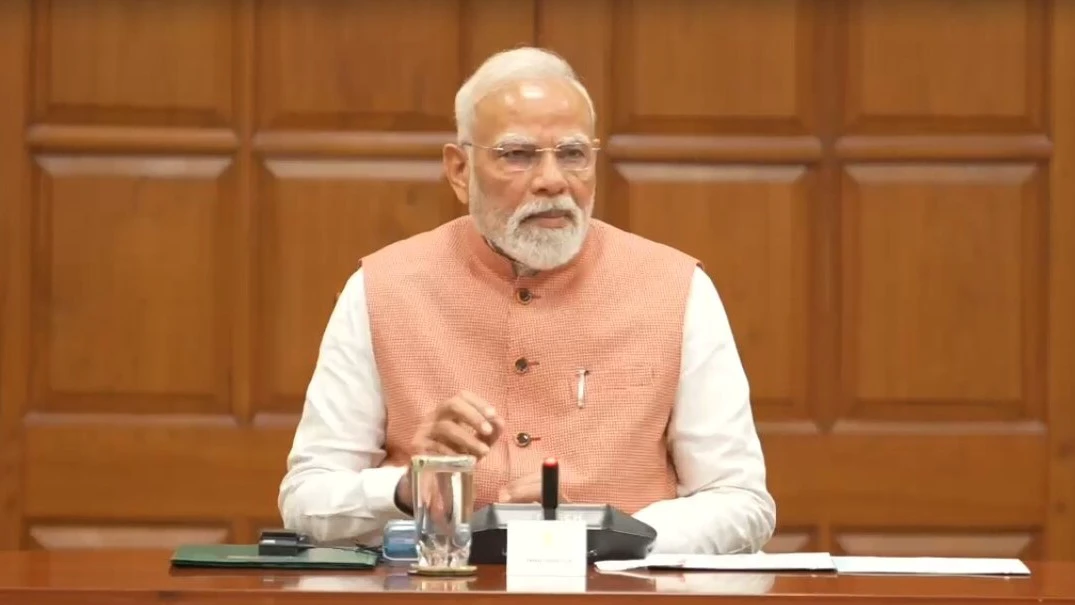

The ongoing discussions present India with a rare opportunity to set a significant precedent. The Prime Minister has emphasized the need to develop ‘Indian Big4s’-firms that can compete globally while leveraging Indian expertise and intellectual property. However, to realize this vision, structural clarity is essential. Consulting and auditing should not be regarded as two arms of an organization. Keeping them separate is not a constraint but a foundation of trust. If India aims to cultivate professional firms capable of scaling globally, it must move from a dotted line to a firm line between consulting and auditing.