“Woman after woman took out one or two of their jewels adorning their bodies and threw them into the handkerchief that he was holding. One threw a diamond and gold ring, another a gold necklace, another a ruby and gold earring, and so on.”

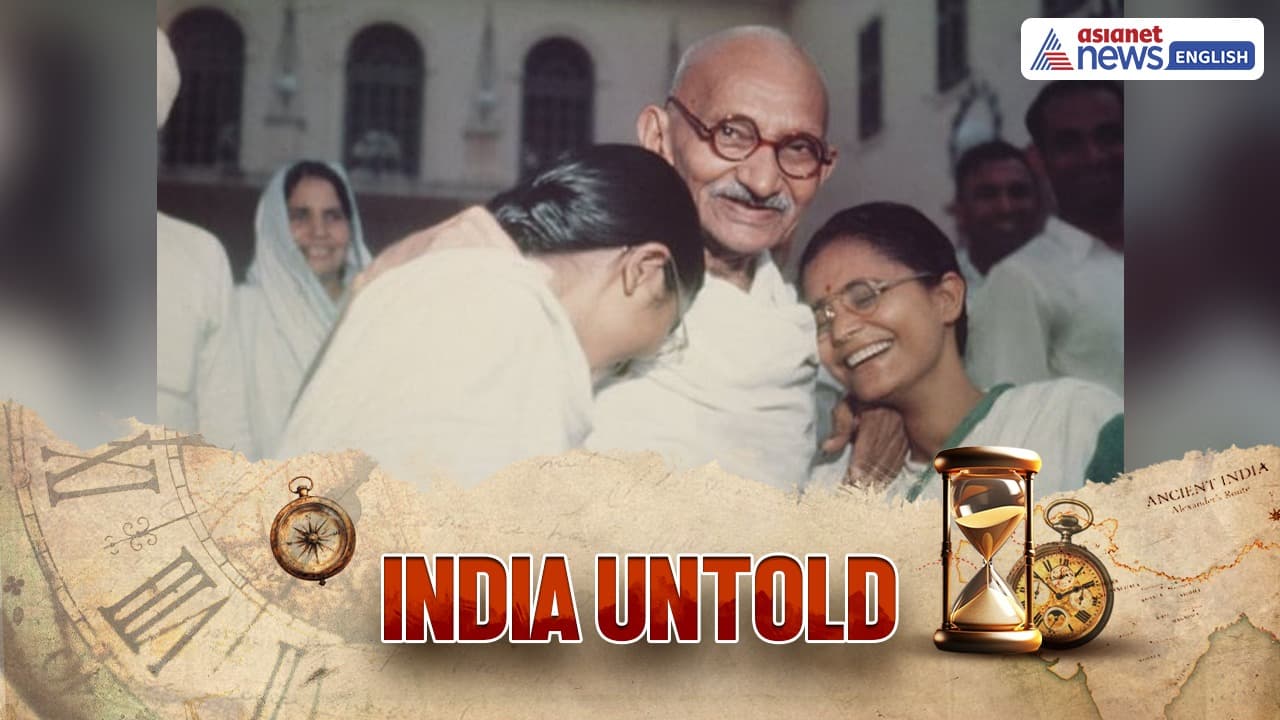

On a sweltering April morning in 1927, as Mahatma Gandhi’s health wavered under the burden of a relentless freedom struggle, he stepped onto the platform at Yeshwanthpur Railway Station. Gandhi, recovering from mild apoplexy and soaring blood pressure, had been advised by his physician to retreat into rest and “a little light reading.” But Gandhi chose not indulgence but discipline. Even with the doctor’s advise to rest, he walked all the way from the railway station to his guest house in Nandi hills for a 45-day period of rest and recuperation. With a diet of fresh goat milk, fruits and homemade bread and days spent just reading and writing letters, his health improved.

By June, his health renewed, Gandhi resumed his mission, addressing eager followers in Bengaluru, determined to draw them into the tide of the freedom movement. His ties with Sir M Visvesvaraya, the celebrated Diwan of Mysore, added nuance to his stay. “While Gandhi was all for rural development, Sir MV promoted industrialisation. The latter advised the Mahatma against prolonging the non-cooperation movement because he felt that it would lead to unionism and more strikes,” Satish Mokshagundam, Sir MV’s grand-nephew, recalled.

From inaugurating a khadi exhibition on July 3rd to calling swadeshi goods the pathway for the “semi-starved millions of India” to rise from poverty, Gandhi’s stay in the city became a turning point. At the Indian Institute of Science and the Imperial Institute for Animal Husbandry & Dairying, he signed the visitors’ book simply as “a farmer from Sabarmati,” vowing to practice in his ashram what he had learned in Bangalore.

When a ‘Sabarmati Farmer’ Persuaded Women to Donate ‘Streedhan

Yet, it was an event at the Mahila Seva Samaja in Basavanagudi that remains etched in collective memory. As women spun the charkha and children sang Vaishnava Janato, Gandhi rose to speak. He asked the assembled women how they could help him in his cause. When they replied that they had no money, Gandhi urged them to part with their ‘streedhan’ — the sacred jewels gifted at marriage, a woman’s only absolute possession.

“Woman after woman took out one or two of their jewels adorning their bodies and threw them into the handkerchief that he was holding. One threw a diamond and gold ring, another a gold necklace, another a ruby and gold earring, and so on.”

Rajeshwari Chatterjee, professor at IISc, recounts that Gandhi “thanked the women of Bangalore for responding to his request, and gracefully left the gathering with his followers.”

Among the first to relinquish their ornaments were Kamalabai Chandur (Rajamma), Subamma, and Gowramma — freedom fighters of old Mysore State — whose gesture inspired countless others. What followed was a cascade of sacrifice, raising an astonishing Rs 90,000 worth of jewellery, a fortune by the standards of 1927.