Scientists discovered why alcohol prevents liver healing even after quitting. Inflammation disrupts RNA splicing, silencing ESRP2 and trapping cells in limbo. Blocking signals restores regeneration, opening new treatment paths beyond transplants.

For years, doctors have puzzled over why people with alcohol-related liver disease often don’t recover, even after giving up drinking. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Duke University finally offers some answers — and hope for better treatments.

The findings are published in the Journal Nature Communications.

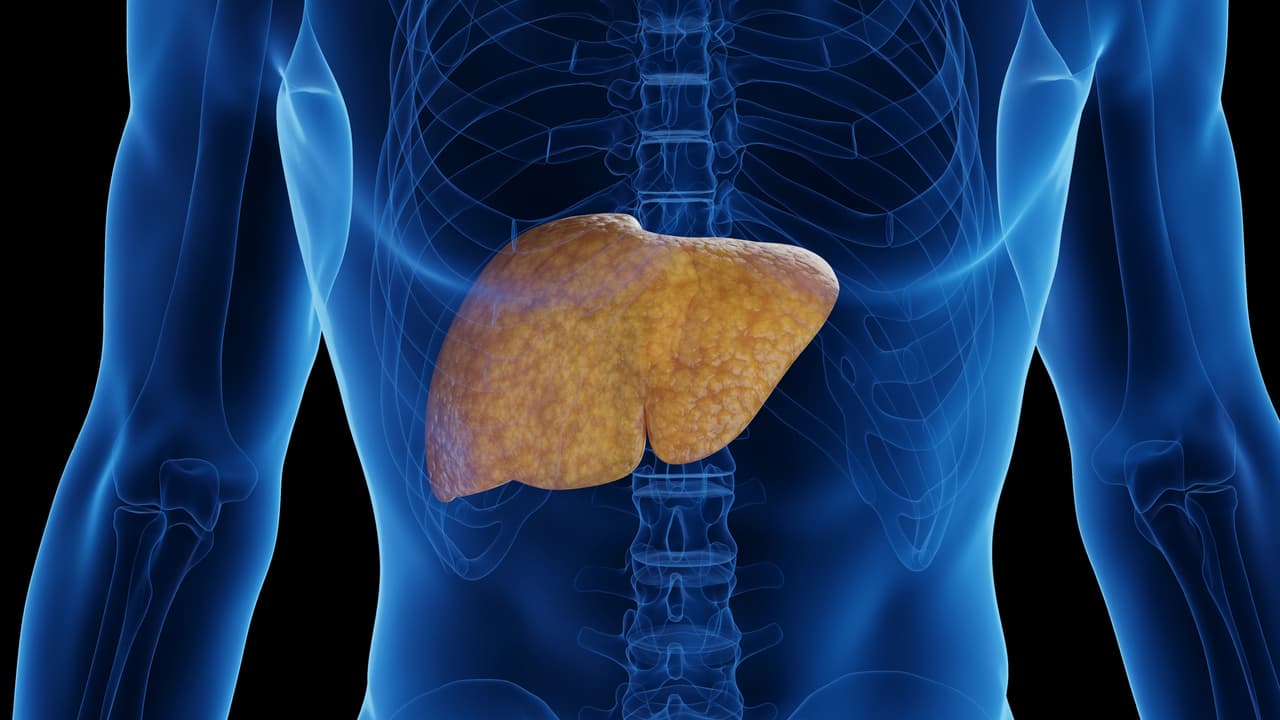

The liver’s superpower — and its limits

The liver is one of the body’s most resilient organs. It can repair itself after injuries or even regrow sections lost during surgery. But in cases of long-term alcohol damage, that superpower shuts down. Patients develop scarring, cirrhosis, and ultimately liver failure, which currently can only be treated with a transplant.

Stuck in limbo

The researchers discovered that liver cells damaged by alcohol don’t fully heal. Instead, they get trapped in a strange in-between state: no longer functioning as mature cells, but unable to fully transform into regenerative cells either. That cellular “limbo” keeps the liver from bouncing back.

What’s causing the block?

The culprit appears to be runaway inflammation. When the liver processes alcohol, it summons immune cells that flood the area with chemical signals. Those signals interfere with RNA splicing — a process that ensures proteins are built correctly inside cells. Without proper splicing, key proteins end up in the wrong place and can’t do their jobs.

One especially important protein, called ESRP2, was found to be missing. Without it, the liver cells can’t correctly reprogram themselves to heal.

A possible way forward

When scientists blocked the inflammatory signals in lab tests, ESRP2 levels returned, the RNA splicing was repaired, and the liver cells regained their ability to regenerate. This suggests future treatments might focus on reducing the inflammation and fixing the splicing errors — potentially sparing patients from needing a transplant.

Hope on the horizon

“Even when patients stop drinking, their livers stay stuck in this dysfunctional state,” said study co-leader Auinash Kalsotra. “If we can find a way to reset the cells, we may finally be able to help these livers heal.”

For the millions of people worldwide suffering from alcohol-related liver disease, this research could mark the beginning of a new chapter — one where quitting alcohol is not just the end of damage, but the start of real recovery.