New Delhi: The immune system recognizes foreign antigens and forms the basis of recognition of self from non-self at the molecular level. The human immune system is extremely dynamic and operates at multiple time scales and dimensions, from the intriguing evolutionary changes that have occurred across generations to variations that occur throughout an individual’s lifetime, and day-to-day changes that occur in the presence of diseases. The interaction between antigens and the immune cells, such as B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, and mononuclear macrophages, forms the basis of our body’s response to infections, transplanted organs, autoimmune conditions, and many cancers.

In an interaction with News9Live, Dr Kishore GSB, Liver Transplant Surgeon, Fortis Hospital, Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore, shared some interesting facts associated with liver transplants and immunology.

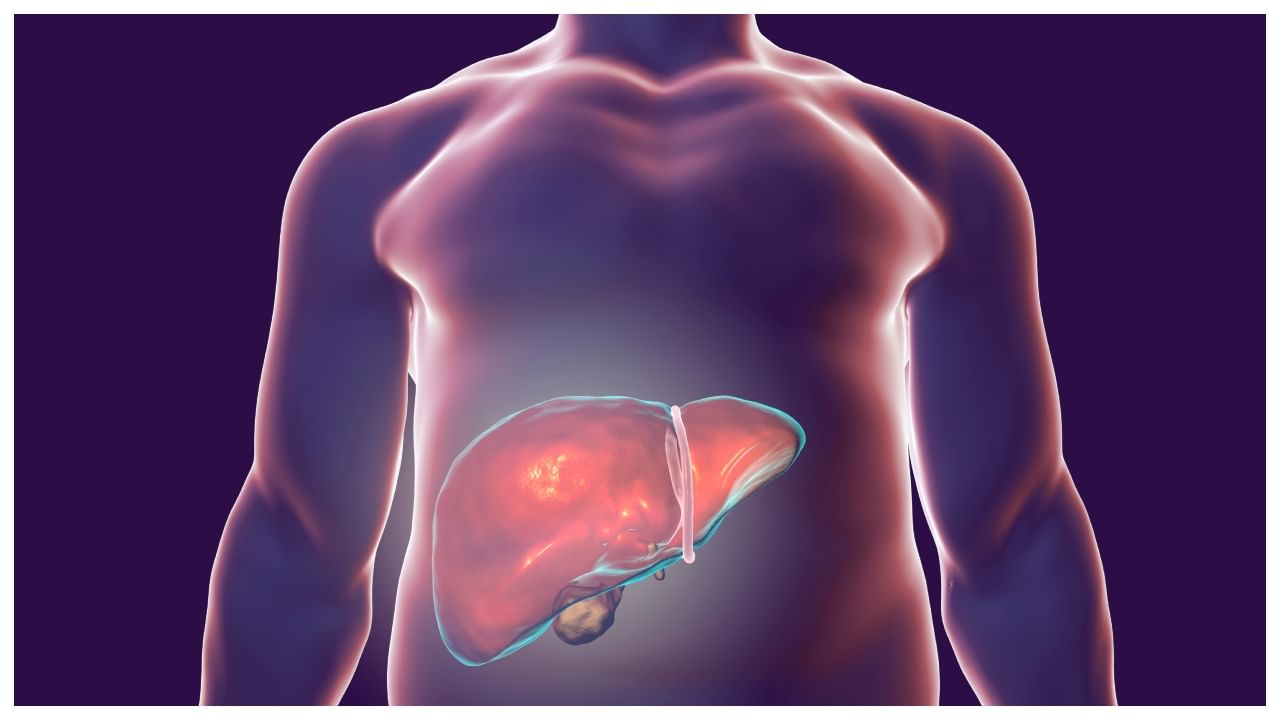

Apart from its remarkable regenerative capacity, roles in protein synthesis, blood clotting function, and regulation of glucose and fat metabolism, the liver is considered a central immunological organ. The liver receives portal blood supply from the entire gastrointestinal tract and is thus exposed to a wide array of antigens and endotoxins every day. With its ultrastructure composed of sinusoids (a scaffolding of specialized endothelial cells through which portal blood passes), the liver plays a key immunological role where interaction of antigens and immune cells occurs. Fine regulation of this orchestra of myriad interactions and maintenance of homeostasis results in a balance between immune tolerance and varying degrees of inflammatory responses.

When a new organ is transplanted into a recipient, the natural tendency of the body is to reject the ‘foreign’ graft. In modern medical practice, immunosuppressants are used to ensure that the organ functions well in its new milieu. In earlier days, while immunology was still evolving, Joseph Murray and his team at Massachusetts performed a kidney transplantation between fraternal twins in 1959. Due to immunologically identical signatures, remarkably, the recipient lived for 20 years after that without the need for immunosuppression. Peter Medawar had shown earlier in the 50s that rejection of skin allografts was an immunological phenomenon and immune tolerance could be actively acquired. This laid the foundation for transplant immunology. Both these remarkable gentlemen have been honoured with the Nobel Prize.

The liver is an immunologically tolerant organ, and rates of rejection of a liver allograft are much lower compared to other transplants, such as kidney or small bowel transplantation. T cells are maintained in a suppressed state by cross-talk between various cells in the liver, such as dendritic cells, Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and stellate cells, to prevent immunological activation and allograft injury. This immunological privilege of the liver also results in lower rejection rates for combined organ transplants such as liver-kidney or liver-intestine transplants as compared to kidney or small bowel alone transplants.

In a small subset of carefully selected liver transplant recipients, operational immunological tolerance has been achieved, whereby patients are free of immunosuppressive medications and their side effects. This is particularly meaningful in paediatric recipients who have a long life ahead. It should be emphasized, however, that in current medical practice, almost all liver recipients are on lifelong immunosuppression to maintain optimal graft function.

Xenotransplantation, or transplantation of organs from other species, is also making headway in recent times. Genetically edited organs from pigs have been shown to function in human beings. This is made possible by preventing the expression of certain proteins on the transplanted organs that trigger a rejection response by the recipient’s immune system. This process has been demonstrated as a proof of concept in individuals who are brain dead after necessary regulatory approvals and informed consent from their families. It is to be seen if xenotransplantation makes inroads into routine clinical practice in the future, as regulatory, ethical, and societal concerns will have to be addressed in addition to advances in medical technology.

The liver’s unique metabolic and immunological profile makes this organ indispensable for a healthy life. Advances in the understanding of immunology hold the key to the future by making transplants more successful and opening new treatment options for many diseases. The liver is inevitably going to be at the centre of all this.