This writer and another journalist were invited to a meeting with Rajendra Singh when he was the RSS sarsanghchalak. We took our seats in a small room at the single-storey RSS headquarters at Jhandewalan in New Delhi.

Rajubhaiya, as Rajendra Singh is called in parivar circles, was seated in one of the chairs. He lived in the anteroom, and moved in and out during the meeting to attend to phone calls.

At the outset, his aide made it clear that this was an informal chat and nothing should appear in public in any form. If it did, they would deny it. The sarsanghchalak had a tradition of avoiding public functions and media interviews other than in exceptional situations, he explained. He was right. In those days, the RSS bosses avoided public events such as seminars and book releases, and journalists looked to their annual Vijayadashami address to understand the nuances of any shifts in policy.

Years later, after Rajubhaiya’s death, the Hindustan Times had carried this writer’s piece on controversial remarks by the RSS boss.

A new RSS

A revisit to the RSS headquarters, Keshav Kunj, three decades after that visit had two takeaways. First, the RSS is no longer a group of spartan pracharaks. Opulence and corporate culture has been permeating its body politic, with its centenary functions managed by event managers.

A swanky 12-storey office complex with three towers, and a total 300 rooms on five lakh square feet, has come up where the pracharaks once worked and lived in monk-like austerity. It has a modern library with 8,500 listings, a five-bed polyclinic with a dispensary, solar electricity, and a sewage treatment and waste recycling plant. The complex boasts state-of-the-art facilities, including auditoriums and conference rooms. The second tower is mainly for residential use. It has parking space for 135 vehicles. In Nagpur, the RSS already has a massive office complex. Security was tightened following new threats, and the whole area was declared drone-free for some time.

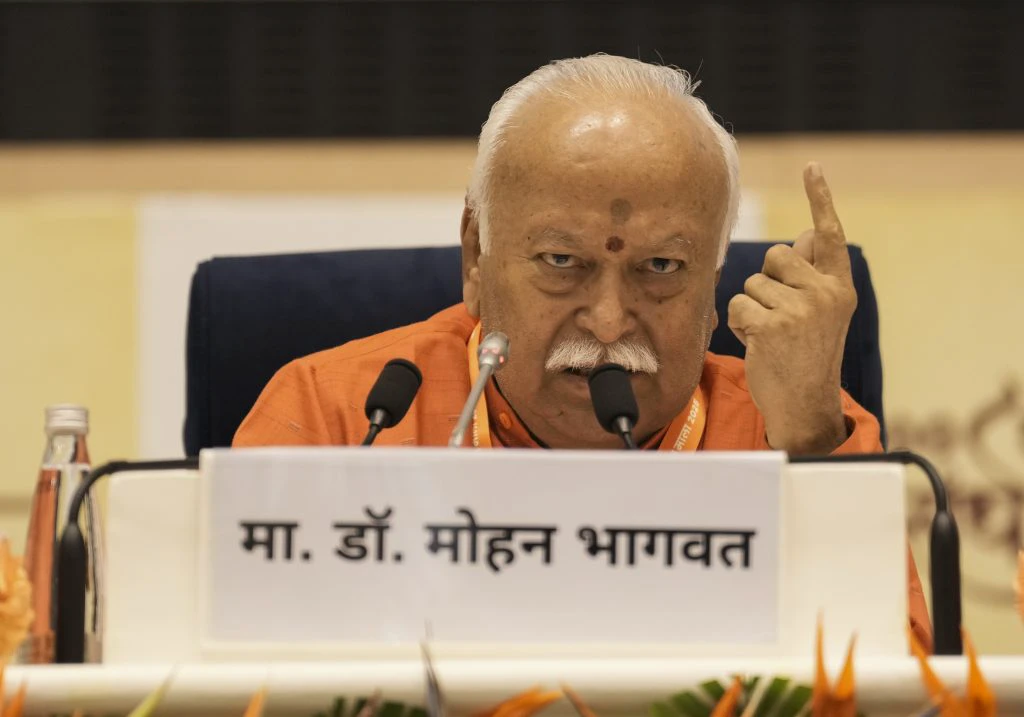

The second visible change relates to the sarsanghchalak’s activist role. Mohan Bhagwat has moved far beyond the description by Rajubhaiya’s aide. Bhagwat, like his predecessor K.S. Sudarshan, did not follow the tradition. We will deal with it later in this piece.

The growth of the RSS is not limited to swanky edifices. On the ground, the RSS is on an expansion spree. Last year, the number of shakhaswent up by 10,000 from 73,117 to 83,129. It expects the figure to reach one lakh by the end of the year. Similarly, 2,500 more pracharaks will be added this year.

The RSS was the ideological inspiration for the Modi government for 11 years. The prime minister and senior ministers holding important portfolios were either one-time pracharaks or paid obeisance to Nagpur. The power and reach of the BJP, the most prominent outfit of the Sangh parivar, is close to 18 crore.

But with all this power and heft, the ability to control the narrative has diminished. This paradox plays out again and again at different levels and in different contexts. Bhagwat’s speeches at different functions, the taunts he throws at the Modi dispensation and his subsequent climbdowns – all point at this.

The reason is that the RSS had at the outset ‘outsourced’ – if we borrow a term from a prominent commentator – policy-making and its implementation to the Modi dispensation, with no requirement for consultations. None of Bhagwat’s predecessors had allowed the BJP such a free hand. The RSS has allowed the Modi-Shah duo to do away with consultations within the BJP organisation and with the RSS. The BJP has become an adjunct to the PMO. Nothing more. It was not so in the past.

Since the BJP was formed in April 1980, the RSS never allowed cult worship within the party. There were sharp differences on endorsing the new economic policies from 1991. A big section led by Murli Manohar Joshi, K.R. Malkani, K.L. Sharma and others opposed the moves by L.K. Advani and Jaswant Singh to support liberalisation. The issue was discussed at three meetings of the national council. At the Ranchi meeting it was decided to discuss it at a chintan baithak of all RSS outfits at Sariska. The final draft was approved at Gandhinagar in May 1992. And thus emerged the document Humanistic Approach to Development – A Swadeshi Alternative. Incidentally, Joshi has reiterated the old swadeshi ideals at a recent closed-door meeting of the RSS outfits.

The tradition of internal debates and independent functioning of the BJP continued under the Vajpayee government. The RSS and the BJP stood by the government even while openly criticising its policies. Vajpayee was forced to call at least a dozen samanvay meetings of RSS and BJP leaders at the prime minister’s residence to sort out differences.

The last one on March 21, 2003, attended by Sudarshan, Bhagwat, Madandas Devi, Advani and other BJP leaders, was held to sort out differences and go into the 2004 elections with full coordination. The RSS had not allowed itself or the BJP to function as an adjunct to the Vajpayee establishment when he was prime minister for six years.

Consider how zealously they preserved their independent identity:

- July 8, 2000: RSS chief K.S. Sudarshan warns Vajpayee against disinvestment in 14 PSUs and 100% FDI

- October 14, 2000: Sudarshan at three-day Agra camp: Vajpayee’s economic policies not in national interest

- May 19, 2001: Jhinjholi chintan baithak, attended by RSS leaders, central and state BJP secretaries, blames the BJP government’s higher taxes for election defeats

- July 31, 2001: Faced with sharp criticism, Vajpayee resigns as prime minister at the national executive but is persuaded to withdraw it

- March 21, 2003: Vajpayee shelves foreign-controlled Sankhya Vahini due to RSS-BJP opposition.

Can you imagine such watchdog roles from the incumbent sarsanghchalak? That is the cost of turning themselves into appendages of the ruling establishment. Hence, it is forced to compromise on the stated RSS tenets such as collective leadership and cult worship.

There isanother paradox. The quick expansion of the RSS base under the patronage of an authoritarian regime has unleashed unruly social forces claiming to represent the real Hindutva ideals. Such powerful local groups, often supported by mobs, have sprung up all over the country, attacking mosques, mazars, and Muslim homes and establishments on every available occasion.

The RSS follows its own calibrated agenda with its long-tern objectives. In many cases, the outgrown Hindutva crowds function parallel to the RSS networks. Adding more embarrassment, such local movements often get the support of vote-hungry local BJP leaders. Nagpur has reasons to fear the rise of such groups as a potential threat to its own credentials.

Bhagwat’s frequent speeches at various functions, the hits and taunts he has thrown at the Modi dispensation over the years and his eventual ‘explanation’ last month – all these point to this paradox. Nagpur appears to be losing its traditional hold over its siblings who have become assertive even while pledging allegiance.

Last December, Bhagwat had warned against raising fresh temple-mosque disputes. There was a big hue and cry against the appeal within the ranks. Even the Organisercontested the RSS chief’s views. Within a month, the VHP and Bajrang Dal held over two dozen Shaurya Yatras in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Assam, Rajasthan and Maharashtra, marked by hate speeches and open threats to minorities. A pro-Modi sadhu said Bhagwat was not the thekedar of Hindu religion.

Finally, at the centenary function last month, Bhagwat climbed down to say that the swayamsevaks were free to join the Kashi-Mathura agitation but the RSS will not. He also said the Modi government was free to chart out its policies. Bhagwat conceded ‘there are struggles within the larger Sangh Parivar, including BJP’ on several issues with no side willing to compromise. “So, we say, you follow your paths.” The RSS had in the past never allowed chaos or revolts by its own siblings.

His speech at a Pune function in December last year advocating an inclusive society and social harmony had caused rumblings among the Hindutva hard liners. In the face of growing defiance, pro-RSS writers argued that Bhagwat was merely ‘charting a more open and inclusive course’.

Also, the ruling elite was aghast when the RSS chief said at a book release that people should step aside when they reach 75. However, a month later he was forced to say, ‘I never said it.’