New Delhi: Scientists analysing 443-million-year-old fossils from Scotland have discovered evidence that some of the earliest vertebrates possessed advanced camera-type eyes and traces of bone-like tissue, altering the views on the early evolution of the vertebrate body plan. The specimens are two species of small, jawless fish Jamoytius and Lasanius, discovered in Silurian rocks near Lesmahagow, south of Glasgow. These soft-bodied creatures are distant relatives of modern lampreys and hagfish. Such creatures leave behind poor fossils because the tissues compress and decay rapidly.

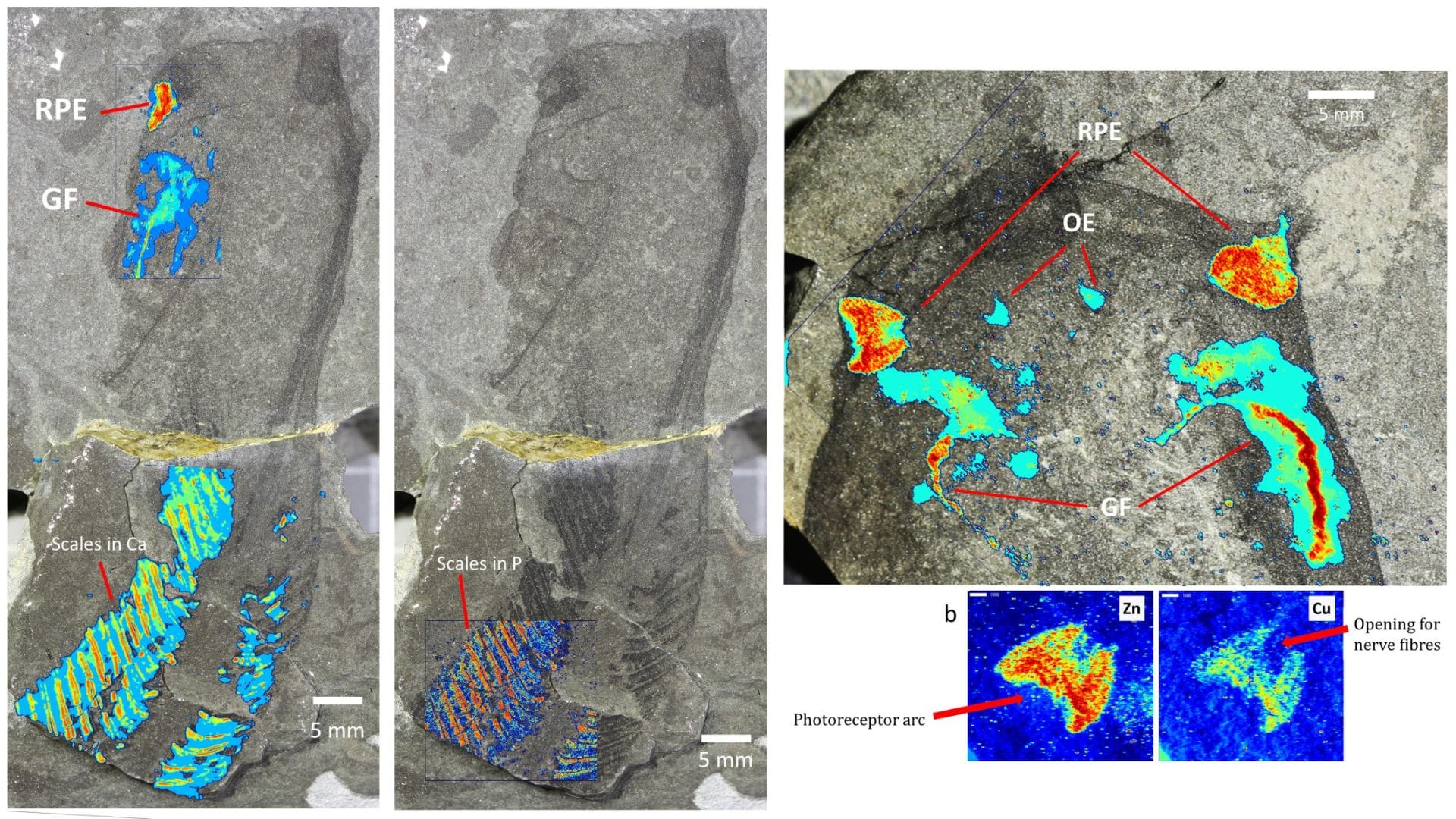

The scientists from the University of Manchester used Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence imaging at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource in California to map chemical elements within the fossils without damaging them. The technique detects low concentrations of elements such as zinc, copper, calcium and phosphorus, revealing the chemistry of preserved tissue under ordinary light. In Jamoytius, the zinc and copper distributions correspond to retinal structures and a pigmented layer in the eyes, including a notch for the optic nerve connection. All of these are hallmarks of camera-type eyes found in later vertebrates.

Results exceeded expectations

The research pushes back the origin of complex features deep into vertebrate history, and resolve long-standing disputes on the anatomy of traditional forms, suggesting that living jawless fish lost such traits over time. The team plans further synchrotron studies on other early vertebrates to trace the evolution of skeletal and sensory systems across major animal groups. A paper describing the research has been published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Scientists have recently discovered that the oldest fossil vertebrate, 518 million years old, had four camera-like eyes.