Children from Tokyo, Berlin, Amsterdam and even a small town in Canada wrote letters to former prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, requesting him to send them an elephant from India.

Children from Tokyo, Berlin, Amsterdam, and even a tiny Canadian town once penned heartfelt letters to India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, requesting for an elephant from India. Nehru, interestingly, turned these requests into small diplomatic victories.

The tales began in wartime Tokyo. In 1943, as World War II consumed the world, the city’s mayor ordered the killing of three elephants at Ueno Zoo — Japan’s oldest zoological park. Fears that the animals might escape during air raids led authorities down a dark path. Two of the elephants, Jon and Tonki, had once journeyed from India in 1924, while the third, Hanako, hailed from Thailand. Adored by children, they became symbols of joy — until tragedy struck.

Attempts to euthanise them with injections failed because of their thick hides. Poisoned meals were refused by the sharp, intuitive animals. Ultimately, starvation was chosen.

Pallavi Aiyar wrote in her book Orienting: An Indian in Japan, “There are accounts of how Tonki, who lasted the longest of the three, desperately performed tricks every time a human passed his enclosure, in the vain hope of some food.” The adults of war-ravaged Tokyo had little time to mourn, but the children never forgot.

A few years later, as Japan began rebuilding, two determined seventh-graders sparked a movement. Their petition to the Japanese Parliament ignited a nationwide campaign, leading to over a thousand letters from schoolchildren—each addressed to India’s prime minister. A 1949 Time Magazine report chronicled this unusual diplomatic surge.

Time noted how young Tokyo students had befriended Himansu Neogy, a Calcutta exporter visiting Japan. “Recently, Tokyo moppets made friends with personable young Himansu Neogy… They begged him to intercede on their behalf with the then prime minister Nehru to send them an Indian elephant.”

Soon after, Neogy delivered a pouch of 815 letters to Nehru’s office. Among them was Sumiko Kanatsu’s earnest plea: “At Tokyo Zoo we can only see pigs and birds which give us no interest… Can you imagine how much we want to see the animal?”

Another child, Masanori Yamato, wrote simply: “The elephant still lives with us in our dreams.”

Nehru responded immediately. He instructed the Ministry of External Affairs to seek an elephant from the princely states. Mysore obliged, and the chosen elephant was christened Indira.

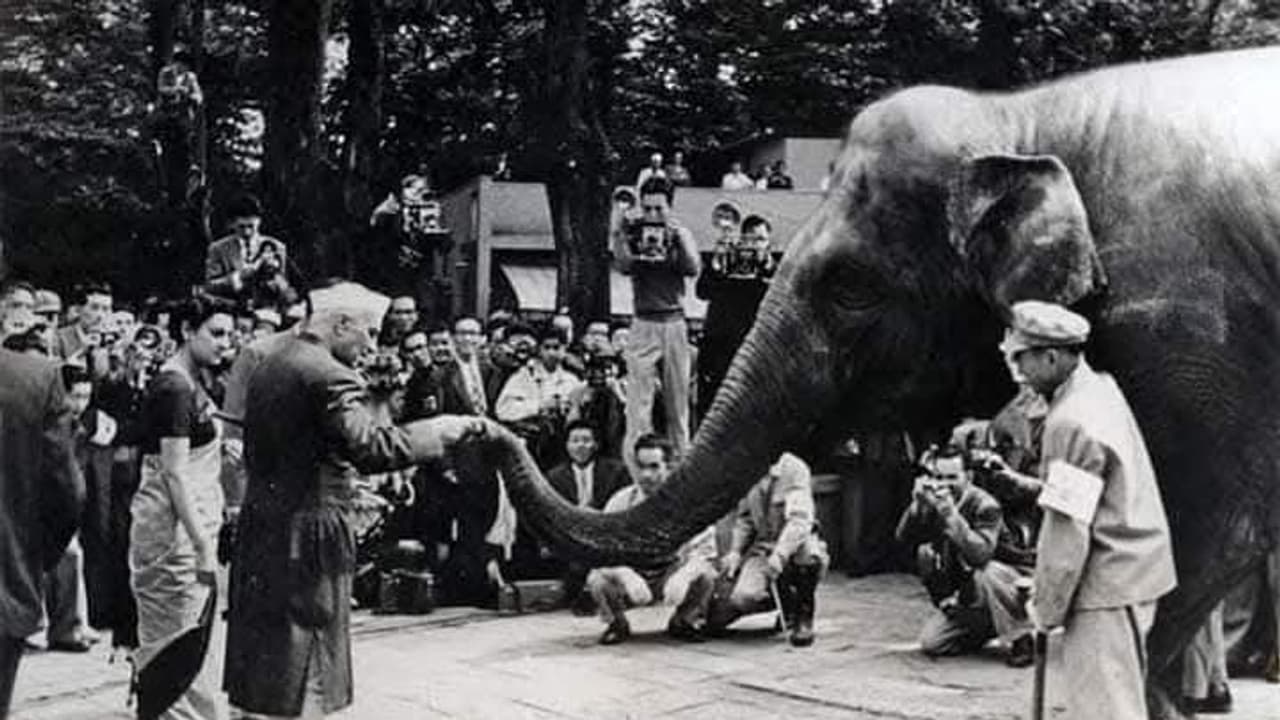

Barely months later, Indira embarked on her voyage to Tokyo. As Aiyar recounts: “Nehru acquiesced, and Indira’s arrival at Ueno on 25 September 1949 caused much excitement…” Zoo chief Tadamichi Koga later said it was one of the happiest moments of his life.

Nehru also issued a message to Japanese children, calling Indira “a messenger of affection and goodwill”, and reminding them that “The elephant is a noble animal… wise and patient, strong and yet, gentle.”

Because Indira only understood commands in Kannada, her Japanese handlers learned the language from two Indian mahouts — a delightful cultural exchange in itself.

In 1957, Nehru and his daughter met Indira in Tokyo, completing a full circle of affection. The elephant remained a symbol of Indo-Japanese friendship until her death.

Nehru’s Global Elephant Diplomacy

Tokyo was only the beginning. Children in Berlin, heartbroken over the wartime loss of their elephants, wrote to Nehru next. He responded by gifting Shanti—a three-year-old elephant whose very name meant “peace”—in 1951.

Then came a whimsical plea from five-year-old Peter Marmorek of Granby, Canada. “Dear Mr Nehru… we have a lovely zoo, but we have no elephant[s]… I never knew that elephants lived underground, [but] I hope you can send us one.”

Nehru gently corrected him: “Elephants do not live underground… It is not easy to catch them.”

The letter became a national sensation in Canada. Thousands of children signed a petition, and in 1955, Ambika — a two-year-old elephant from Madras forests — arrived in Canada. Marmorek welcomed her, though nervously. His comic worry became a local legend: “But how does the elephant know that I’m not a vegetable?”

A similar request soon arrived from the Netherlands, where Murugan — a calf from the Malabar forests — was sent to Amsterdam in 1954. He lived there till 2003.

Why Elephants? The Larger Diplomacy Behind the Gesture

While Nehru adored children, these gifts were far from mere sentiment. As historian Nikhil Menon explains, gifting elephants projected post-colonial India as generous, confident, and eager to foster global friendship.

The Indian High Commission in Canada wrote, “No doubt it will be an appealing gesture of friendliness and goodwill.” Social worker Kameshwari Kuppuswamy put it simply: “The only way by which we can show our appreciation and return the kindness is by way of sending something which your country does not possess.”

India’s elephant diplomacy not only delighted children worldwide but shaped the nation’s image as a compassionate rising power. The practice ended in 2005 when India banned international animal transfers.

Reflecting in 2005, Marmorek wrote: “Ambika from whom I had learned that India was a magical country; if you wrote to it, they would send you an elephant.”